The Health Care Cost-Coverage Conundrum

The Care We Want vs. The Care We Can Afford

Annual Essay 2002-03

Fall 2003

Paul B. Ginsburg, Len M. Nichols

![]() merican health care—often lauded as the best in the world—is too expensive and growing more so every day. As a result,

too many Americans go without vital medical care because they are

unable to afford health insurance without substantial public subsidies.

How we finance health care and our leaders’ pervasive unwillingness

to confront the difficult trade-offs inherent in containing health

care costs and expanding health insurance to more Americans

contribute to the seemingly intractable nature of the cost-coverage

conundrum. To start an honest discussion, three factors are key:

merican health care—often lauded as the best in the world—is too expensive and growing more so every day. As a result,

too many Americans go without vital medical care because they are

unable to afford health insurance without substantial public subsidies.

How we finance health care and our leaders’ pervasive unwillingness

to confront the difficult trade-offs inherent in containing health

care costs and expanding health insurance to more Americans

contribute to the seemingly intractable nature of the cost-coverage

conundrum. To start an honest discussion, three factors are key:

• Cost-containment and quality-improvement efforts are essential if Americans are to get better value for the tremendous amount of money-$1.4 trillion annually-spent on U.S. health care.

• If we are to cover everyone, we cannot cover everything, and we need to make informed choices about which medical services are more beneficial to patients than others.

• Even if we slow cost trends, significant public funding will be needed to expand coverage to the estimated 43.6 million uninsured Americans, whether through tax subsidies, expansion of public coverage or a combination of both approaches.

- Spending Beyond Our Means

- Health Care Costs Are High...

- ...and Costs Are Rising Rapidly

- As the Business Cycle Turns: Employers and Rising Costs

- Government and Rising Costs

- Other Approaches

- A Call for Leadership

![]() eflecting on the U.S. experience with

health care cost containment, what is

striking is the consistency with which leaders

in both the public and private sectors have

avoided the idea that real cost containment

involves real sacrifice—patients going without

services that may provide some benefit or

physicians, hospitals and insurers settling for

smaller incomes or profits. Policy makers have

long described the cost problem in terms of

"waste, fraud and abuse," as if feasible further

reductions of these would reduce costs

enough that trade-offs would not have to be

made.

eflecting on the U.S. experience with

health care cost containment, what is

striking is the consistency with which leaders

in both the public and private sectors have

avoided the idea that real cost containment

involves real sacrifice—patients going without

services that may provide some benefit or

physicians, hospitals and insurers settling for

smaller incomes or profits. Policy makers have

long described the cost problem in terms of

"waste, fraud and abuse," as if feasible further

reductions of these would reduce costs

enough that trade-offs would not have to be

made.

Despite our aggregate economic capacity to pay for ever-greater health care spending,1 an increasing number of individuals can no longer afford health care when society acts as if medical care is a free good. In our view, a more clinically based form of rationing is needed to avoid pricing health care out of the reach of an increasing proportion of Americans. Though some deny it, we ration care today. The uninsured get much less care than the insured and suffer worse health outcomes because of it,2 and the insured with ample means get more care than the lower-income insured, although without clear differences in outcomes. The challenge is to ration in a way that is more efficient and more equitable.

Spending Beyond Our Means

After a significant respite in the mid-1990s during the zenith of tightly managed care, Americans are again struggling with health care costs rising substantially faster than incomes. A recent Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study showed that the costs underlying private health insurance increased by 9.6 percent per capita in 2002, compared with an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) of 2.7 percent per capita.3 Premium trends for employer-sponsored insurance are even higher, growing an average of 14 percent in 2003, with another round of double-digit increases forecast for 2004.

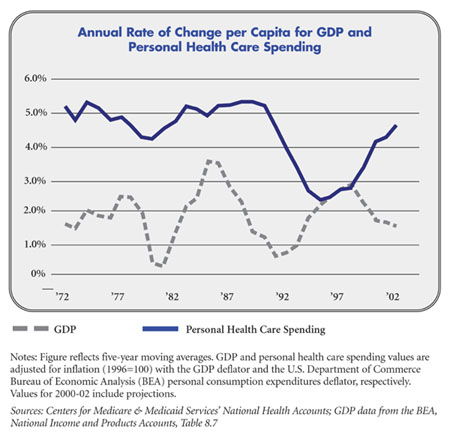

The phenomenon of health care cost trends exceeding income trends is longstanding and experienced throughout the world. In the United States, personal health care spending has consistently grown faster— about 2.5 percentage points a year—than GDP in the last 30 years (see Figure). At the same time, U.S. personal health care spending as a percentage of GDP has more than doubled.

Even though other industrialized countries devote smaller percentages of GDP to health spending, their health care costs per capita have grown at rates remarkably similar to those in the United States. All developed countries are spending an increasing share of GDP on health and increasingly are worried about cost control, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The magnitude of difference between U.S. health spending growth and income growth has not been constant. On a number of occasions in past decades, public or private initiatives have slowed the rate of cost growth substantially, only to be followed by periods of particularly rapid growth.4 To understand spending-growth fluctuations over time, it’s important to examine why U.S. health care costs are high to begin with and identify factors driving changes in the spending trend.

|

Health Care Costs Are High...

A combination of factors contributes to high U.S. health care costs, with the way most health care is financed among the most critical. Since the need for health care is uncertain, insurance pools are necessary to provide the wherewithal to pay for expensive services needed by the relatively few who are seriously ill at any particular time. Unlike most other forms of insurance, such as life or fire, the benefits of health insurance are not predetermined or defined in terms of a distinct event—you die or your house burns down. Instead, health insurers’ financial obligations are defined in terms of what treatments physicians and patients decide to pursue—providing an environment in which treatment decisions can be made with little regard for treatment costs.When someone else pays—the health insurer—patients have little price sensitivity and almost no incentive to economize and make sure the expenditure is commensurate with the clinical value of the service.

The impact of low patient out-of-pocket costs—coupled with payment systems that encourage providers to deliver more services—is probably magnified by limited information about the effectiveness of many medical tests and procedures. Little information on comparative effectiveness of medical goods and services is produced by the private market because of the public good nature of this information—once in the public domain, it will benefit those who did not pay for it. But limited public funding for effectiveness research is puzzling, given the clear interests of public and private payers—not to mention taxpayers. To date, providers and developers of medical technology have been more effective politically than proponents of technology assessment.

...and Costs Are Rising Rapidly

Health care costs are not just high; they are rising rapidly as well. We know that much of the long-term trend toward greater percapita spending is driven by technological change—new diagnostic tests and treatments and new applications of older technologies. But rapid technology diffusion would not be possible without a financing system that pays most of the cost of all services and institutionalizes few mechanisms to screen new techniques and devices for clinical effectiveness prior to coverage. And a major downside to the status quo is that a significant proportion of Americans—the 15.2 percent without health insurance—have limited access to all the wonders of modern medicine.

At the same time, hospitals and physicians are making the most of the reprieve from managed care’s aggressive cost-containment tactics. Providers have focused primarily on two strategies to bolster their financial position—pressing health plans for better payment rates and contract terms and investing in select services and technology that are particularly well compensated, especially cardiac, cancer and orthopedic services. Many medical groups are opening ambulatory surgery and diagnostic centers and adding capacity to deliver radiology, laboratory and imaging services in their practices. The intense competition for niche specialty services may be an indication that public and private payers are inadvertently overpaying for some services while underpaying for others.

As the Business Cycle Turns: Employers and Rising Costs

Employers’ willingness to tackle cost control ebbs and flows with the business cycle.When health care costs are rising rapidly, profits are low and labor markets are loose, employers have taken strong actions to control costs, only to abandon their efforts when the cycle turns. As an example, in the early 1990s, employers responded to these conditions by adopting restrictive models of managed care. In effect, they hired private insurers to slow cost growth by imposing administrative controls on access to care and striking better deals with providers. But during the late-1990s’ economic boom, when recruiting and retaining workers was perceived as more important than containing health benefit outlays, employers retreated in the face of worker complaints about restrictions on provider choice and access to care.

Now, with premium trends high again and the economy weaker, employers are responding by buying down the benefit structure of their plans by increasing patient cost sharing.While employers don’t appear to be interested in revisiting restrictive managed care models, they also are not optimistic that higher cost sharing alone is the long-term answer.Why employers opted for higher cost sharing rather than a return to restrictive managed care probably reflects the intensity of at least some employees’ dislike of managed care restrictions, perhaps abetted by the lack of visibility of costs to workers.

Government and Rising Costs

State and federal governments deal with costs through two distinct roles—as managers of public insurance programs and as regulators of the health care system.Medicare and Medicaid have aggressively controlled spending when imperatives to cut budgets were greatest. The most heavily used tool has been to reduce provider payment rates. But rate reductions have been constrained by concerns about beneficiaries’ access to providers and concerns about providers’ financial viability—especially hospitals’.

Benefit reductions have not been common, although budget constraints likely explain why Medicare did not add a prescription drug benefit in the 1970s, when such coverage became the norm in private health insurance. Governments have been less inclined to control utilization of services, partly due to statutory prohibitions against interferring with the practice of medicine. Medicaid programs have successfully delegated some utilization review to managed care companies, but the Medicare program has faced intense opposition to mandating, or even favoring, managed care.

Except for the 1970s, governments as regulators have not been very active in attempts to contain costs systemwide. Hospital rate regulation, adopted by a number of states in the 1970s and unsuccessfully proposed at the federal level by President Jimmy Carter, was one exception. These programs had some success, but most were abandoned in the 1990s as the nation turned away from regulation in general, and because the combination of Medicare prospective payment and managed care contracting were perceived as adequate constraints on hospital costs. Certificate-of-need (CON) legislation—which limited major capital expenditures by hospitals and some other facilities based on the recognition that unneeded facilities increased costs, either by creation of excess capacity or by inducing additional use of services—was more widespread and continues to this day in many states. But most research shows that CON programs had little impact on capital spending in the aggregate, although they did have substantial impact on which institutions expanded facilities.

Other Approaches

In contrast to the United States, OECD countries use a wider array of tools to limit resource use and expenditure growth. Until recently, cost sharing has not been used in these countries, often reflecting their social value of solidarity—equal access to something as critical as health care. Direct regulation of prices, involving unabashed use of government’s sole-buyer purchasing power, and administrative limits on the acquisition and use of expensive technology are used in place of substantial patient cost sharing in these systems. A recent analysis concluded that rates of service use are lower in the United States than in OECD countries and that higher service prices and greater service intensity explain much of the higher U.S. spending rate.5

Initiatives to collect and distribute more information on medical effectiveness, to reduce medical errors and to screen the development of new technologies all presume a rich lode of services that are being delivered today and that will turn out to have little medical benefit to patients. This may be true, and there is compelling evidence from Medicare that suggests higher-than average spending in many areas of the country does not buy better outcomes; in fact,much of the spending variation comes from services in which guidelines based on effectiveness research do not exist.6 Recent research has pointed out that many quality problems in U.S. medicine are associated with underprovision of services that are known to be effective for specific types of patients.7 Thus, while more widespread application of evidence-based practice would surely improve the quality of care, it may not reduce health care use and cost.

A Call for Leadership

The next few years are likely to be a period of particularly intense concern about costs. Increased patient cost sharing is likely to convince the public there is a cost problem, though some may focus more on who pays what share rather than on how much we all pay. Government budgets probably will be tight for some time, and policy makers will find growing outlays for Medicare and Medicaid increasingly intolerable. Private insurers and employers will complain more loudly about government reimbursement cuts being shifted to them. More employers and employees are going to find themselves priced out of the comprehensive health insurance market. Some will take cold comfort in plans with increasingly high deductibles, and others, faced with the choice of expensive comprehensive insurance for broad provider networks or being uninsured, will opt to take the risk and depend on the safety net in the event of serious illness. Hospitals will be alarmed by the increasing diversion of resources to provide uncompensated care to the uninsured and to cover bad debts owed by those who are insured.

Policy makers will likely pursue ideas that promise to reduce costs, including federal support for an information technology infrastructure for hospitals and medical practices and an expanded role for disease management in Medicare and Medicaid.Many of these initiatives have merit because they may improve the quality of care, but we are skeptical about the magnitude of cost reduction. While there certainly will be instances where quality improvement will contain costs at the same time, we doubt that the net impact on costs will be commensurate with the magnitude of the affordability problem.

More effective ways to cope with limited resources will depend on political, professional, corporate, labor and opinion leaders articulating the need to confront trade-offs among clinical effectiveness, costs and equity. Once the rationing imperative is widely acknowledged, a broader and complementary array of cost-containment tools can be brought to bear in the United States. These cannot and need not extend to the kinds of absolute limits on specific resources and consumer choices used by the centralized systems of most OECD countries. Rather, evidence-based practice guidelines and institutionalized technology assessment can help to inform private benefit package design and differential cost-sharing requirements. In contrast to systems that decide for the patient what services are unavailable because of limited clinical value, a system more compatible with American values would continue to allow broad patient and provider choices, coupled with extensive information about likely clinical value and higher cost sharing when the values are small.

Acknowledging that relying on cost sharing alone will ultimately increase segmentation of insured risk pools by socioeconomic class over time, we should also be mindful of the dynamic that is driving increasing fractions of workers to decline coverage over time.8 Today, many lower-income workers are essentially being denied the opportunity to opt for lower cost and more tightly managed care products, such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs)—the type now extensively and successfully relied on by some employers and by Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program—because higher-income people have objected to health care restrictions, especially on their choice of provider.

Some restrictive provider networks are capable of delivering high-quality care; indeed, systematic evaluations of the relative quality of HMOs and fee-for-service medicine have always concluded that average quality was about the same.9 Results from HSC’s Community Tracking Study surveys have shown consistently over time that the public is divided in its willingness to have more restrictive provider choice in return for lower costs, with low-income people much more willing to make that trade-off. Purchasing vehicles and subsidies can be created to permit low-income workers to exercise this choice, while providing time to develop the more sophisticated mechanisms needed to vary cost sharing based on the clinical value of services.

There is much we do not know about how to do effective clinical value rationing at the moment. Estimates of the fraction of physicians’ care decisions that are supported by unambiguous clinical trial evidence range from 11 percent to 65 percent depending on specialty and care setting.10 A strong case can be made that these estimates are upper bounds, since the studies focus on major decisions only and not the full range of care decisions—such as whether to hospitalize a patient or consult with another specialist—that are made in any complex treatment regimen.11

Chronic disease management, provider payment incentive systems and widespread distribution of comparative quality information are all relatively new and will need to be improved before they serve the bulk of patients, payers and providers well. But the time to pretend that we do not need massive public investment and private participation in the development of these cost-quality tools has long since passed. In the end, we still will be devoting more of our income to health care than is the case today, but slowing that trend may keep mainstream health care accessible to more of the population. It also could give us considerably more clinical value for our health care dollars and help ensure that care will be distributed far more equitably throughout our society than if we do nothing.

Notes

| 1. | Chernew,Michael E., Richard A. Hirth and David M. Cutler, "Increased Spending on Health Care: How Much Can the United States Afford?" Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 4 (July/August 2003). |

| 2. | Institute of Medicine, Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. (2002). |

| 3. | Strunk, Bradley C., and Paul B. Ginsburg, "Tracking Health Care Costs: Trends Stabilize but Remain High in 2002," Health Affairs, Web Exclusive (June 11, 2003). |

| 4. | Altman, Drew E., and Larry Levitt, "The Sad History of Health Care Cost Containment as Told in One Chart," Health Affairs, Web Exclusive (Jan. 23, 2002). |

| 5. | Anderson, Gerard F., et al., "It’s the Prices, Stupid:Why the United States is so Different from Other Countries," Health Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 3 (May/June 2003). |

| 6. | Fisher, Elliott S., et al., "The Implications of Regional Variations in Medicare Spending," Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 138, No. 4 (Feb. 18, 2003). |

| 7. | McGlynn, Elizabeth A., et al., "The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States," New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 348, No. 26 (June 26, 2003). |

| 8. | Farber, Henry S., and H. Levy, "Recent Trends in Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Coverage: Are Bad Jobs Getting Worse?" Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January 2000). |

| 9. | Miller, Robert H., and Harold L. Luft, "HMO Plan Performance Update: An Analysis of the Literature, 1997-2001," Health Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 4 (July/August 2002). |

| 10. | "What Proportion of Healthcare is Evidence Based? Resource Guide," www.shef.ac.uk/~scharr/ir/percent.html, accessed Sept. 12, 2003. |

| 11. | We are grateful to Elliott Fisher for this point. |

Back to Top

HSC COMMENTARIES are published by

the Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Vice President: Len M. Nichols