Physicians Slow to Adopt Patient E-mail

Data Bulletin No. 32

September 2006

Allison Liebhaber, Joy M. Grossman

![]() ecently, two health care trends—consumerism and

health information technology (IT)—have converged as interest grows in

helping patients more effectively manage their care. The American Health Information

Community (AHIC), a recently formed federal commission, identified secure online

communication between physicians and patients—especially those with chronic

conditions—as one of a limited number of “breakthrough” information technologies

targeted for rapid development.1 Moreover, public opinion

polls show that 80 percent of online Americans would like to communicate with

their doctors via e-mail.2

ecently, two health care trends—consumerism and

health information technology (IT)—have converged as interest grows in

helping patients more effectively manage their care. The American Health Information

Community (AHIC), a recently formed federal commission, identified secure online

communication between physicians and patients—especially those with chronic

conditions—as one of a limited number of “breakthrough” information technologies

targeted for rapid development.1 Moreover, public opinion

polls show that 80 percent of online Americans would like to communicate with

their doctors via e-mail.2

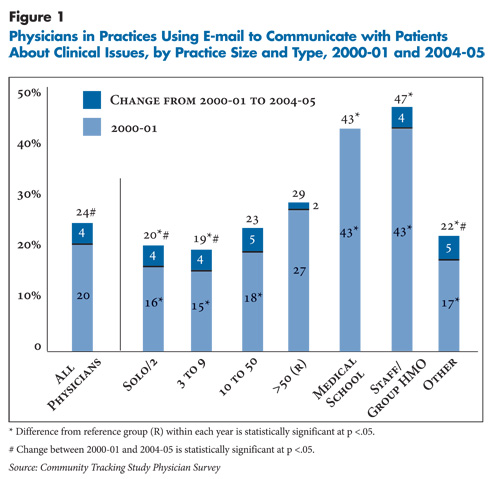

Nevertheless, physician adoption of patient e-mail is growing slowly and remains low. Only about one in four physicians (24%) reported that e-mail was used in their practice to communicate clinical issues with patients in 2004-05, up from one in five physicians in 2000-01, according to HSC’s nationally representative Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey (see Figure 1 and Data Source).3 The 20 percent growth in physician-patient e-mail between 2000-01 and 2004-05 lagged growth in access to IT for other clinical activities, such as writing prescriptions and accessing patient notes.4

Electronic messaging tools for physician-patient communications have expanded beyond traditional unencrypted e-mail to include encrypted e-mail and newer secure platforms, such as Web portals and electronic medical record systems. While policy makers are promoting secure online communication, the CTS survey estimates reflect physician practice adoption of the broad array of both secure and unsecure e-mail tools.

Who Will Pay?

![]() ack of reimbursement for e-mail consultations reportedly

is a major barrier to physician adoption.5 Some health

plans are testing payment for e-mail consultations, but reimbursement remains

limited. A few practices are experimenting with charging patients directly,

but whether and how much patients will be willing to pay out of pocket is unclear.

Moreover, implementing a secure messaging system is more costly than using unencrypted

e-mail, and physicians are less likely to make such an investment without payment

for electronic consultations. Physicians also fear e-mail will add to their

workload instead of substituting for face-to-face or telephone consultations.

While some studies have shown e-mail can improve physician efficiency and patient

satisfaction by providing more timely communication, even less is known about

the effects of e-mail use on quality of care.6

ack of reimbursement for e-mail consultations reportedly

is a major barrier to physician adoption.5 Some health

plans are testing payment for e-mail consultations, but reimbursement remains

limited. A few practices are experimenting with charging patients directly,

but whether and how much patients will be willing to pay out of pocket is unclear.

Moreover, implementing a secure messaging system is more costly than using unencrypted

e-mail, and physicians are less likely to make such an investment without payment

for electronic consultations. Physicians also fear e-mail will add to their

workload instead of substituting for face-to-face or telephone consultations.

While some studies have shown e-mail can improve physician efficiency and patient

satisfaction by providing more timely communication, even less is known about

the effects of e-mail use on quality of care.6

Large Practice E-mail Adoption Stalls

![]() hysician-patient e-mail is most common in larger practices.

In 2004-05, physicians in staff/group health maintenance organizations (HMOs)

and medical school faculty practices reported the highest rates of adoption

(47% and 43%, respectively), followed by group practices of more than 50 physicians

(29%). Smaller practices lagged behind; for example, about 20 percent of physicians

in practices with nine or fewer physicians reported e-mail use in their practice.

hysician-patient e-mail is most common in larger practices.

In 2004-05, physicians in staff/group health maintenance organizations (HMOs)

and medical school faculty practices reported the highest rates of adoption

(47% and 43%, respectively), followed by group practices of more than 50 physicians

(29%). Smaller practices lagged behind; for example, about 20 percent of physicians

in practices with nine or fewer physicians reported e-mail use in their practice.

However, growth in e-mail adoption essentially stalled in larger practices between 2000-01 and 2004-05. At the same time, smaller practices with nine or fewer physicians did have statistically significant growth in e-mail use. The stagnant growth among large practices—traditionally early IT adopters—suggests e-mail use is not progressing rapidly.

Some Patients Lack E-mail Access

![]() hysician decisions about adopting e-mail differ from other

clinical IT because patients also must be able and willing to use e-mail. Rural,

low-income, elderly and African-American consumers are among those less likely

to have Internet access and, if they have it, to use e-mail.7

Practices with higher proportions of such patients may move more cautiously

to offer e-mail consultations because of more limited patient demand and capability.

Indeed, physicians in practices in nonmetropolitan areas, practices with high

Medicaid and/or high Medicare revenue and practices with a high percent of African-American

patients (data not shown) are less likely to report e-mail is used to communicate

with patients, and e-mail growth in these practices has stagnated as well (see

Table 1).

hysician decisions about adopting e-mail differ from other

clinical IT because patients also must be able and willing to use e-mail. Rural,

low-income, elderly and African-American consumers are among those less likely

to have Internet access and, if they have it, to use e-mail.7

Practices with higher proportions of such patients may move more cautiously

to offer e-mail consultations because of more limited patient demand and capability.

Indeed, physicians in practices in nonmetropolitan areas, practices with high

Medicaid and/or high Medicare revenue and practices with a high percent of African-American

patients (data not shown) are less likely to report e-mail is used to communicate

with patients, and e-mail growth in these practices has stagnated as well (see

Table 1).

Table 1

|

|

2000-01

|

2004-05

|

||

| Location | |||

| Metropolitan (R) |

21%

|

26%#

|

|

| Nonmetropolitan |

11*

|

11*

|

|

| Medicaid Revenue | |||

| <25% of Practice Revenue (R) |

20

|

25#

|

|

| >25% of Practice Revenue |

20

|

20*

|

|

| Medicare Revenue | |||

| <50% of Practice Revenue (R) |

21

|

26#

|

|

| >50% of Practice Revenue |

16*

|

18*

|

|

| Specialty | |||

| Primary Care |

18

|

24#

|

|

| Surgical Specialist |

23*

|

28*#

| |

| Medical Specialist (R) |

20

|

22

|

|

| Physician Age | |||

| Younger than 35 |

18

|

20*

|

|

| 35 to 54 (R) |

21

|

25#

|

|

| Older than 54 |

17*

|

24#

|

|

|

Note: Nonmetropolitan areas include micropolitan and rural areas. Micropolitan

areas, as defined by the White House Office of Management and Budget,

are generally nonmetro counties with an urban area between 10,000 and

50,000 in population or that meet specified commuting criteria to an urban

area. For purposes of this analysis, rural areas are generally nonmetro

counties that do not meet the micropolitan definition. Source: Community Tracking Study Physician Survey |

|||

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | Barrett, Craig, and Mark McClellan, Draft AHIC Chronic Care Workgroup Recommendation Letter (May 1, 2006). |

| 2. | Gullo, Kelly, Many Nationwide Believe in the Potential Benefits of Electronic Medical Records and are Interested in Online Communications with Physicians, HarrisInteractive Health Care Poll (March 2005). |

| 3. | Because physicians were asked whether e-mail is used in their practice to discuss clinical issues with patients but not whether they themselves use it or the frequency of use, the estimates presented here are an upper bound on the proportion of physicians regularly using e-mail to communicate with patients. |

| 4. | Reed, Marie C., and Joy M. Grossman, Growing Availability of Clinical Information Technology in Physician Practices, Data Bulletin No. 31, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (June 2006). |

| 5. | Katz, Steven J., and Cheryl A. Moyer, “The Emerging Role of Online Communication Between Patients and Their Providers,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 19 (September 2004). |

| 6. | Car, Josip, and Aziz Shiekh, “Email Consultations in Health Care: 1—Scope and Effectiveness, and 2—Acceptability and Safe Application” BMJ, Vol. 329 (August 2004). |

| 7. | See Pew Internet and American Life Project. Data available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/. |

Data Source

This Data Bulletin presents findings from the HSC Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of physicians involved in direct patient care in the continental United States conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99, 2000-01 and 2004-05. The sample of physicians was drawn from the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association master files and included active, nonfederal, office- and hospital-based physicians who spent at least 20 hours a week in direct patient care. Residents and fellows were excluded. Questions on information technology were added to the 2000-01 survey and continued in the 2004-05 survey. The 2000-01 survey contains information on about 12,000 physicians, while the 2004-05 survey includes responses from more than 6,600 physicians. The response rates were 52 percent (2004-05) and 59 percent (2000-01). More detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.