Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

HMO Model Shaken but Remains Intact

Orange County, Calif.

Community Report No. 09

Summer 2001

Aaron Katz, Robert E. Hurley, Leslie A. Jackson, Timothy K. Lake, Ashley C. Short, Paul B. Ginsburg, Joy M. Grossman

n January 2001, a team of researchers

visited Orange County, Calif., to study

that community’s health system, how

it is changing and the effects of those

changes on consumers. The Center for

Studying Health System Change

(HSC), as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more

than 80 leaders in the health care market.

Orange County is one of 12

communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to Orange

County, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are tracked.

The Orange County market encompasses

an area of about 30 cities south

of Los Angeles. n January 2001, a team of researchers

visited Orange County, Calif., to study

that community’s health system, how

it is changing and the effects of those

changes on consumers. The Center for

Studying Health System Change

(HSC), as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more

than 80 leaders in the health care market.

Orange County is one of 12

communities tracked by HSC every

two years through site visits and surveys.

Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to Orange

County, in 1996 and 1998, provided

baseline and initial trend information

against which changes are tracked.

The Orange County market encompasses

an area of about 30 cities south

of Los Angeles.

Despite sustained turmoil in the Orange County health care market, health maintenance

organizations (HMOs) continue to dominate. The market remains unique, not only

because of extensive enrollment in HMOs, but also because large physician organizations

assume much of the financial risk and care management that is typically within

health plans’ purview. Plans, providers and consumers have been comfortable with

this arrangement, so Orange County has not yet seen the shift from HMOs to preferred

provider organizations (PPOs) experienced elsewhere.

Nevertheless, turmoil among physician organizations

shook the market two years ago, and several recent

developments continue to threaten its stability:

- The market’s largest physician practice management

company (PPMC) declared bankruptcy, jeopardizing

access and quality for patients.

- A premier hospital system, along with affiliated

physicians, terminated its contract with the market’s

leading health plan, disrupting access to care.

-

The market is bracing for a rapid rise in its historically low HMO premiums, which

may result in higher consumer cost sharing and expansion of PPOs.

Unstable Provider Networks Provoke Concerns

ince 1998, two major disruptions have

shaken and destabilized provider networks

in Orange County. The first was

the bankruptcy in November 2000

of KPC Medical Management, the area’s

largest PPMC. The second was a decision

by the largest provider, St. Joseph Health

System, to drop several HMO contracts,

including its contract with PacifiCare, one

of the county’s leading longtime health

plans. These disruptions have heightened

concerns among consumers, health

plans and employers and increased regulatory

scrutiny.

KPC’s Demise. KPC’s abrupt closure of 38 clinics and the subsequent bankruptcy

temporarily disrupted access to medical care for up to 300,000 people. Furthermore,

KPC’s failure to transmit patient records and test results in a timely manner-attributed

to the group’s financial distress-raised concerns about quality of care.

The demise of KPC signaled the end

of the PPMC model in Orange County.

PPMCs were designed to organize large

numbers of physicians into networks to

accept financial risk, streamline practice

management and negotiate with health

plans. Once expected to flourish in Orange

County, PPMCs have struggled since 1998.

Two forerunners to KPC-MedPartners

and FPA, Inc.-failed in 1998, disrupting

patient care in the county and raising questions

about the state’s role in overseeing

capitated payment arrangements between

provider organizations and health plans.

KPC’s financial difficulties ignited a

political and public relations battle between

state medical and health plan associations,

and California policy makers took several

steps to intervene. Gov. Gray Davis’

administration encouraged several health

plans to contribute to a financial assistance

package to keep KPC operating. Although

a $30 million loan package was negotiated,

KPC failed nonetheless. After KPC filed

for bankruptcy protection, a judge installed

a new director of the organization to ensure

that medical records were distributed to

patients’ new providers as quickly as possible

to avoid the protracted problems

that occurred two years ago.

The newly created state Department

of Managed Health Care also stepped in

to ensure access to care by working with

health plans to facilitate the transfer of

KPC patients to other providers. The

agency was not able to be more proactive

because KPC’s operating status was not

within the purview of California regulators.

Newly issued rules requiring physician

organizations to report financial data are

intended to improve oversight and to

avoid future problems.

St. Joseph and PacifiCare Part Ways. In a bold move, St. Joseph Health

System announced in June 2000 that it would terminate all 14 of its existing HMO

contracts and, through a competitive bidding process, select five plans with which

it would establish five-year contracts. The system’s decision to terminate its

contract with PacifiCare, which St. Joseph says will stand for at least five years,

ended a long-standing relationship between the two organizations. About half of

the 100,000 PacifiCare members in Orange County who received care at St. Joseph

may change insurers so they can remain with their St. Joseph provider when the

current contract ends in July 2001.

Consumer Concerns Grow. KPC’s bankruptcy and St. Joseph’s contract termination

have increased concerns among health plans and purchasers that provider network

instability will jeopardize access, continuity of care and customer service. Some

health plans, such as Blue Shield and CIGNA, have tried to pull members out of

failing physician organizations to avert access and quality problems. To prevent

organizational failures and improve physician organizations’ overall financial

and clinical performance, nearly all plans have devised surveillance and consultation

strategies.

Employers are concerned that employees

will have a diminishing choice of providers.

Some employers dropped PacifiCare when

St. Joseph terminated its contract, but others

have taken a wait-and-see approach.

Because the St. Joseph/PacifiCare break

occurred after many employers had made

their 2001 plan offerings, its full effect on

employees may not be seen until next year. ince 1998, two major disruptions have

shaken and destabilized provider networks

in Orange County. The first was

the bankruptcy in November 2000

of KPC Medical Management, the area’s

largest PPMC. The second was a decision

by the largest provider, St. Joseph Health

System, to drop several HMO contracts,

including its contract with PacifiCare, one

of the county’s leading longtime health

plans. These disruptions have heightened

concerns among consumers, health

plans and employers and increased regulatory

scrutiny.

KPC’s Demise. KPC’s abrupt closure of 38 clinics and the subsequent bankruptcy

temporarily disrupted access to medical care for up to 300,000 people. Furthermore,

KPC’s failure to transmit patient records and test results in a timely manner-attributed

to the group’s financial distress-raised concerns about quality of care.

The demise of KPC signaled the end

of the PPMC model in Orange County.

PPMCs were designed to organize large

numbers of physicians into networks to

accept financial risk, streamline practice

management and negotiate with health

plans. Once expected to flourish in Orange

County, PPMCs have struggled since 1998.

Two forerunners to KPC-MedPartners

and FPA, Inc.-failed in 1998, disrupting

patient care in the county and raising questions

about the state’s role in overseeing

capitated payment arrangements between

provider organizations and health plans.

KPC’s financial difficulties ignited a

political and public relations battle between

state medical and health plan associations,

and California policy makers took several

steps to intervene. Gov. Gray Davis’

administration encouraged several health

plans to contribute to a financial assistance

package to keep KPC operating. Although

a $30 million loan package was negotiated,

KPC failed nonetheless. After KPC filed

for bankruptcy protection, a judge installed

a new director of the organization to ensure

that medical records were distributed to

patients’ new providers as quickly as possible

to avoid the protracted problems

that occurred two years ago.

The newly created state Department

of Managed Health Care also stepped in

to ensure access to care by working with

health plans to facilitate the transfer of

KPC patients to other providers. The

agency was not able to be more proactive

because KPC’s operating status was not

within the purview of California regulators.

Newly issued rules requiring physician

organizations to report financial data are

intended to improve oversight and to

avoid future problems.

St. Joseph and PacifiCare Part Ways. In a bold move, St. Joseph Health

System announced in June 2000 that it would terminate all 14 of its existing HMO

contracts and, through a competitive bidding process, select five plans with which

it would establish five-year contracts. The system’s decision to terminate its

contract with PacifiCare, which St. Joseph says will stand for at least five years,

ended a long-standing relationship between the two organizations. About half of

the 100,000 PacifiCare members in Orange County who received care at St. Joseph

may change insurers so they can remain with their St. Joseph provider when the

current contract ends in July 2001.

Consumer Concerns Grow. KPC’s bankruptcy and St. Joseph’s contract termination

have increased concerns among health plans and purchasers that provider network

instability will jeopardize access, continuity of care and customer service. Some

health plans, such as Blue Shield and CIGNA, have tried to pull members out of

failing physician organizations to avert access and quality problems. To prevent

organizational failures and improve physician organizations’ overall financial

and clinical performance, nearly all plans have devised surveillance and consultation

strategies.

Employers are concerned that employees

will have a diminishing choice of providers.

Some employers dropped PacifiCare when

St. Joseph terminated its contract, but others

have taken a wait-and-see approach.

Because the St. Joseph/PacifiCare break

occurred after many employers had made

their 2001 plan offerings, its full effect on

employees may not be seen until next year.

Back to Top

Capitated, Delegated Managed

Care Survives—for Now

anaged care has long been widespread

and aggressive in Orange County. HMO

penetration hovers around 50 percent,

and health plans continue to delegate

considerable financial risk to providers-

including not only physicians’ fees, but

also ancillary services and sometimes

hospital care. The recent provider network

instability and continued turmoil

among physician organizations are a sign,

however, that big changes may be on

the horizon.

Hospitals in Orange County, like their

counterparts nationally, have experienced

financial hardship from reductions in

Medicare revenue under the 1997 Balanced

Budget Act and rising costs. In addition,

many Orange County and other California

hospitals must renovate facilities to comply

with state seismic standards, an

undertaking that could require as much

as $24 billion in hospital capital spending

statewide (reportedly more than the total

value of existing facilities) by 2030.

Moreover, labor shortages, which have

been driving up costs nationally, have

been particularly severe in Orange County,

where as many as 20 percent of hospital

nursing positions are vacant.

In response to such pressures, many

hospitals are refusing to accept capitated

payment for their services. Tenet Healthcare

Corp., which operates 10 hospitals in the

county, and the University of California-

Irvine Medical Center have decided to

drop capitation payment as their HMO

contracts come up for renewal. Similarly,

St. Joseph has eliminated hospital capitation

in newly negotiated contracts.

Meanwhile, physician organizations-

which typically bear the lion’s share of

financial risk in the Orange County market-

have continued to struggle under

capitation rates that they contend have

not kept pace with rising costs. Many are

now trying to shed risk for ancillary services

such as pharmacy or injectable

drugs, which they view as too difficult

and unpredictable to manage. Physician

organizations are retaining risk for professional

services but pushing for higher

capitation rates to cover costs.

Market observers worry that providers’

dramatic pushback on risk contracting

and demand for higher payments eventually

may undermine the substantial price

advantage HMOs have enjoyed in the

county and open the market to growth

of more expensive and less aggressively

managed products, such as PPOs. In fact,

driven by fears of more provider network

instability and already rising premiums,

health plans are positioning themselves

for a possible shift toward PPOs by

preparing for fee-for-service contracts

with individual physicians.

Any shift away from HMOs in Orange

County is still down the road, because

many physician organizations and health

plans in the market remain firmly committed

to the fully delegated model of

capitated managed care. Indeed, large

barriers stand in the way of such a shift:

Physician organizations would have to

greatly expand their ability to bill for

services, and health plans would have to

develop the capacity to manage service

utilization now handled by physician

practices. anaged care has long been widespread

and aggressive in Orange County. HMO

penetration hovers around 50 percent,

and health plans continue to delegate

considerable financial risk to providers-

including not only physicians’ fees, but

also ancillary services and sometimes

hospital care. The recent provider network

instability and continued turmoil

among physician organizations are a sign,

however, that big changes may be on

the horizon.

Hospitals in Orange County, like their

counterparts nationally, have experienced

financial hardship from reductions in

Medicare revenue under the 1997 Balanced

Budget Act and rising costs. In addition,

many Orange County and other California

hospitals must renovate facilities to comply

with state seismic standards, an

undertaking that could require as much

as $24 billion in hospital capital spending

statewide (reportedly more than the total

value of existing facilities) by 2030.

Moreover, labor shortages, which have

been driving up costs nationally, have

been particularly severe in Orange County,

where as many as 20 percent of hospital

nursing positions are vacant.

In response to such pressures, many

hospitals are refusing to accept capitated

payment for their services. Tenet Healthcare

Corp., which operates 10 hospitals in the

county, and the University of California-

Irvine Medical Center have decided to

drop capitation payment as their HMO

contracts come up for renewal. Similarly,

St. Joseph has eliminated hospital capitation

in newly negotiated contracts.

Meanwhile, physician organizations-

which typically bear the lion’s share of

financial risk in the Orange County market-

have continued to struggle under

capitation rates that they contend have

not kept pace with rising costs. Many are

now trying to shed risk for ancillary services

such as pharmacy or injectable

drugs, which they view as too difficult

and unpredictable to manage. Physician

organizations are retaining risk for professional

services but pushing for higher

capitation rates to cover costs.

Market observers worry that providers’

dramatic pushback on risk contracting

and demand for higher payments eventually

may undermine the substantial price

advantage HMOs have enjoyed in the

county and open the market to growth

of more expensive and less aggressively

managed products, such as PPOs. In fact,

driven by fears of more provider network

instability and already rising premiums,

health plans are positioning themselves

for a possible shift toward PPOs by

preparing for fee-for-service contracts

with individual physicians.

Any shift away from HMOs in Orange

County is still down the road, because

many physician organizations and health

plans in the market remain firmly committed

to the fully delegated model of

capitated managed care. Indeed, large

barriers stand in the way of such a shift:

Physician organizations would have to

greatly expand their ability to bill for

services, and health plans would have to

develop the capacity to manage service

utilization now handled by physician

practices.

Back to Top

Providers Redirect Market Strategies

n the late 1990s, provider efforts in Orange County and elsewhere

emphasized integrating inpatient and outpatient services, thereby creating networks

or systems that could take risk for and coordinate the whole range of medical

care. The failure of risk-bearing intermediaries and growing pressures on revenues

and capacity-from population increases, labor shortages and low payment rates-have

led to a shift away from integration strategies among both hospitals and physicians.

Hospitals Build, Specialize. As Orange County hospitals move away from

capitated payment arrangements, they increasingly have focused on building revenue-

generating services. This strategy is motivated in part by changed financial incentives

and in part by newly emerging capacity problems. After trying to reduce excess

capacity for years, many prominent hospitals apparently now face capacity constraints.

Hospitals attribute this change to labor shortages, growing demand for services

and, thanks to more accommodating HMO products, greater consumer leeway in choosing

providers.

Hospitals have responded by turning

their attention to building inpatient and

outpatient capacity, improving their brand

identities in both geographic and product

markets and developing specialty-focused,

centers of excellence. For example: n the late 1990s, provider efforts in Orange County and elsewhere

emphasized integrating inpatient and outpatient services, thereby creating networks

or systems that could take risk for and coordinate the whole range of medical

care. The failure of risk-bearing intermediaries and growing pressures on revenues

and capacity-from population increases, labor shortages and low payment rates-have

led to a shift away from integration strategies among both hospitals and physicians.

Hospitals Build, Specialize. As Orange County hospitals move away from

capitated payment arrangements, they increasingly have focused on building revenue-

generating services. This strategy is motivated in part by changed financial incentives

and in part by newly emerging capacity problems. After trying to reduce excess

capacity for years, many prominent hospitals apparently now face capacity constraints.

Hospitals attribute this change to labor shortages, growing demand for services

and, thanks to more accommodating HMO products, greater consumer leeway in choosing

providers.

Hospitals have responded by turning

their attention to building inpatient and

outpatient capacity, improving their brand

identities in both geographic and product

markets and developing specialty-focused,

centers of excellence. For example:

- Hoag Memorial is planning to build a new

patient tower with an obstetrics/gynecology

focus and outpatient cardiology and

oncology facilities.

- Similarly, St. Joseph Hospital is building a new patient care tower and new

cardiology and oncology outpatient units in partnership with specialty physicians.

- MemorialCare, which has increased its capacity by buying two hospitals, is

striving to establish its identity as the county’s premier, high-quality hospital

system.

Physician Organizations Largely Intact. The physician market in Orange

County remains highly organized, despite KPC’s demise. Large primary care or multispecialty

physician groups and independent practice associations (IPAs) -some of which were

part of KPC- continue to dominate the county’s landscape and wield considerable

clout with health plans.

For example, Monarch Healthcare IPA, the largest independent physician organization

in the market, contracts with 800 physicians, including 250 primary care physicians,

most of whom practice in small groups or solo practices. Monarch serves about

150,000 HMO enrollees, including 20,000 Medicare+Choice enrollees. The IPA has

substantial negotiating leverage with health plans and strong leverage over local

physicians practicing in southern Orange County.

Damage from the MedPartners/KPC downfall and historically low fees continue to

affect physician practices, and many of the preexisting groups have shrunk. Most

of the physician organizations that were acquired by MedPartners have become independent

again, but many physicians in these organizations have moved to smaller practices.

Moreover, physician organizations are widely perceived to be in worse financial

condition as a result of years of inadequate investment and the need for more

working capital than usual because of late payments from plans.

Back to Top

Plans See Enrollment Shifts,

Employers Face Premium Hikes

lthough the number of major health plans in Orange County

has changed little in the past two years, turbulence in provider contracts and

impending health plan premium increases have created instability and uncertainty

in the health plan market (see box). Indeed, by March 2001,

PacifiCare’s large Medicare product, Secure Horizons, had already lost 10,000

members in Orange County. Adding to PacifiCare’s woes nationally were leadership

turnover, strict federal caps on Medicare payment increases and a sharp drop in

its stock price.

Recent federal limits on payment increases for Medicare managed care plans also

are a cause of concern. Though the Medicare+Choice market in Orange County is

still attractive to health plans and beneficiaries-42 percent are in HMOs-plans

are trimming benefits and putting enrollees on notice for more changes down the

line. PacifiCare, whose Secure Horizons is the nation’s largest Medicare HMO and

covers more than 60,000 enrollees in Orange County, reduced its prescription drug

benefit, and Kaiser added a $20 monthly premium for its 23,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Observers expect these types of changes to increase enrollment shifts among major

health plans in the local Medicare market.

More turmoil is expected in the

county’s commercial market as employers

brace for double-digit premium increases

from health plans. Some employers are

trying to hold down cost increases in the

short term through benefit modifications,

such as increasing consumer copayments

and deductibles and instituting three-tiered

pharmacy benefits. For example, the

California Public Employees’ Retirement

System (CalPERS)-viewed as a bellwether

for employer benefit strategies locally and

nationally-responded to proposed double-digit

premium increases for its fully insured

HMO products in 2002 by rejecting all

HMO contracts and requesting new bids.

This tactic, along with increased copay-ments

for office visits and prescription

drugs, allowed CalPERS to hold its HMO

premium increases to 6 percent.

Employers worry that the higher payment rates obtained by St. Joseph and other

providers, along with increased utilization rates and prescription drugs costs,

will push premiums up even faster over the next few years. Meanwhile, dissatisfaction

with the quality of customer service by carriers is rising among both employers

and employees, adding impetus for a potential move away from HMOs in favor of

more loosely managed products such as PPOs. lthough the number of major health plans in Orange County

has changed little in the past two years, turbulence in provider contracts and

impending health plan premium increases have created instability and uncertainty

in the health plan market (see box). Indeed, by March 2001,

PacifiCare’s large Medicare product, Secure Horizons, had already lost 10,000

members in Orange County. Adding to PacifiCare’s woes nationally were leadership

turnover, strict federal caps on Medicare payment increases and a sharp drop in

its stock price.

Recent federal limits on payment increases for Medicare managed care plans also

are a cause of concern. Though the Medicare+Choice market in Orange County is

still attractive to health plans and beneficiaries-42 percent are in HMOs-plans

are trimming benefits and putting enrollees on notice for more changes down the

line. PacifiCare, whose Secure Horizons is the nation’s largest Medicare HMO and

covers more than 60,000 enrollees in Orange County, reduced its prescription drug

benefit, and Kaiser added a $20 monthly premium for its 23,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Observers expect these types of changes to increase enrollment shifts among major

health plans in the local Medicare market.

More turmoil is expected in the

county’s commercial market as employers

brace for double-digit premium increases

from health plans. Some employers are

trying to hold down cost increases in the

short term through benefit modifications,

such as increasing consumer copayments

and deductibles and instituting three-tiered

pharmacy benefits. For example, the

California Public Employees’ Retirement

System (CalPERS)-viewed as a bellwether

for employer benefit strategies locally and

nationally-responded to proposed double-digit

premium increases for its fully insured

HMO products in 2002 by rejecting all

HMO contracts and requesting new bids.

This tactic, along with increased copay-ments

for office visits and prescription

drugs, allowed CalPERS to hold its HMO

premium increases to 6 percent.

Employers worry that the higher payment rates obtained by St. Joseph and other

providers, along with increased utilization rates and prescription drugs costs,

will push premiums up even faster over the next few years. Meanwhile, dissatisfaction

with the quality of customer service by carriers is rising among both employers

and employees, adding impetus for a potential move away from HMOs in favor of

more loosely managed products such as PPOs.

Back to Top

Tobacco Money Galvanizes

Safety Net

range County’s fragile safety net system

appears to be getting stronger and more

organized. Many are optimistic that the

state’s new tobacco-related funds, along

with existing and expanding public insurance

programs, will help improve the overall

capacity of both community clinics and

major safety net hospitals. On the other

hand, local political conflicts, potential state

and federal program budget constraints and

a possible economic downturn could threaten

the well-being of safety net providers and

uninsured families alike.

Funds from the new state tobacco

tax and the state’s tobacco settlement

promise important gains for the local

safety net. Orange County has set aside

part of its $50 million allocation from the

state tobacco tax to develop comprehensive

health and early childhood development

programs for children under 6. This

money will help to expand access at the

region’s two major safety net hospitals,

Children’s Hospital of Orange County

and University of California-Irvine Medical

Center. The state also plans to allocate $24

million a year in tobacco settlement funds

to health services that will benefit safety

net providers as well. Community clinics

in Orange County, for example, will receive

about $3.5 million for expansions.

In addition, the State Children’s

Health Insurance Program (SCHIP),

Healthy Families, has expanded coverage

to about one-third of the county’s estimated

90,000 uninsured children, thanks

largely to targeted outreach efforts by

community organizations. A recent

expansion of eligibility for children and a

newly submitted federal waiver to expand

Healthy Families to the parents of eligible

children are expected to help even more.

CalOPTIMA, a quasi-public agency that

oversees the county’s Medicaid managed

care program, has been instrumental in

the success of Healthy Families-and the

continued strength of the safety net-in

coordinating outreach and new strategies

to address the uninsured.

Despite these improvements, the safety

net and uninsured families in Orange County

remain vulnerable. First and foremost, many

observers fear that if the economy worsens,

uninsurance will grow beyond the already

high rate of one in five people. The rising

number of non-English-speaking immigrants

presents an added challenge to the

local safety net. Many advocates worry

that the county’s limited medically indigent

program leaves many needy people without

care and, because of its low payment

levels, increases the charity care burden

on providers. And while advocates are

buoyed by expanded public programs

and funding, they worry that tobacco

revenues will dry up and that federal or

state budget decisions-perhaps as fallout

from the state’s energy crisis-will jeopardize

recent coverage expansions. range County’s fragile safety net system

appears to be getting stronger and more

organized. Many are optimistic that the

state’s new tobacco-related funds, along

with existing and expanding public insurance

programs, will help improve the overall

capacity of both community clinics and

major safety net hospitals. On the other

hand, local political conflicts, potential state

and federal program budget constraints and

a possible economic downturn could threaten

the well-being of safety net providers and

uninsured families alike.

Funds from the new state tobacco

tax and the state’s tobacco settlement

promise important gains for the local

safety net. Orange County has set aside

part of its $50 million allocation from the

state tobacco tax to develop comprehensive

health and early childhood development

programs for children under 6. This

money will help to expand access at the

region’s two major safety net hospitals,

Children’s Hospital of Orange County

and University of California-Irvine Medical

Center. The state also plans to allocate $24

million a year in tobacco settlement funds

to health services that will benefit safety

net providers as well. Community clinics

in Orange County, for example, will receive

about $3.5 million for expansions.

In addition, the State Children’s

Health Insurance Program (SCHIP),

Healthy Families, has expanded coverage

to about one-third of the county’s estimated

90,000 uninsured children, thanks

largely to targeted outreach efforts by

community organizations. A recent

expansion of eligibility for children and a

newly submitted federal waiver to expand

Healthy Families to the parents of eligible

children are expected to help even more.

CalOPTIMA, a quasi-public agency that

oversees the county’s Medicaid managed

care program, has been instrumental in

the success of Healthy Families-and the

continued strength of the safety net-in

coordinating outreach and new strategies

to address the uninsured.

Despite these improvements, the safety

net and uninsured families in Orange County

remain vulnerable. First and foremost, many

observers fear that if the economy worsens,

uninsurance will grow beyond the already

high rate of one in five people. The rising

number of non-English-speaking immigrants

presents an added challenge to the

local safety net. Many advocates worry

that the county’s limited medically indigent

program leaves many needy people without

care and, because of its low payment

levels, increases the charity care burden

on providers. And while advocates are

buoyed by expanded public programs

and funding, they worry that tobacco

revenues will dry up and that federal or

state budget decisions-perhaps as fallout

from the state’s energy crisis-will jeopardize

recent coverage expansions.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

he Orange County health market is a place of contrasts. All

players-providers, insurers, purchasers and consumers- continue to rely on HMO

products and delegated risk and care management. In addition, managed care is

highly successful and stable in the Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP programs. But

the ongoing turmoil in physician organizations and in provider-health plan relations

may lead to dramatic changes. As the market continues to unfold, the following

issues will be important to track: he Orange County health market is a place of contrasts. All

players-providers, insurers, purchasers and consumers- continue to rely on HMO

products and delegated risk and care management. In addition, managed care is

highly successful and stable in the Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP programs. But

the ongoing turmoil in physician organizations and in provider-health plan relations

may lead to dramatic changes. As the market continues to unfold, the following

issues will be important to track:

- Will increasing provider payment and

scrutiny of physician organization finances

help to stabilize the provider market? If

so, how will health plan premiums and

consumer access to care be affected?

- Will purchasers respond to rising premiums by reducing benefits or shifting

costs to consumers?

- To what extent will PPOs and other less restricted network products emerge,

and how will they be received by purchasers, consumers and providers long

accustomed to HMOs?

- Will collaborations involving new tobacco-related

funding be sustained and result

in stronger and more widely accessible

safety net services?

Back to Top

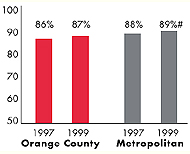

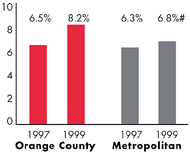

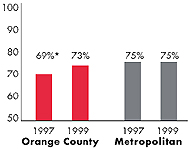

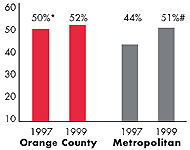

Orange County’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997

and 1999

Back to Top

Background and Observations

| Orange County Demographics |

| Orange County |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

2,760,948 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 15% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $30,635 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 11% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 11% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Orange County |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 18% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 15% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 81% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $156 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Orange County |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 2.1 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 2.2 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 46% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 46% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

Back to Top

Instability and Uncertainty among Health Plans: Who Benefits?

ith PacifiCare under duress, the pole position among Orange County health

plans appears to be shifting to Kaiser, which has grown steadily over the past five

years to more than 300,000 enrollees. Kaiser has bounced back from the financial

stress and capacity problems that were evident in 1998. Furthermore, it has

escaped—and, indeed, benefited from—provider network stability issues because

of its group-model structure built around an exclusive relationship with a single

large medical group and affiliated hospitals. Kaiser reportedly is ahead of its competitors

in its use of disease management initiatives and Web-based communications

with consumers, in part because members stay with the health plan for an average

of 12 years.

Other health plans may benefit from shifts and uncertainty in Orange County’s

health insurance market. Some health plans that already offer PPOs—such as

Wellpoint’s Blue Cross of California, Blue Shield of California, CIGNA and Aetna—

may be more agile in the changing health plan market. These plans have developed

individual, nonrisk contracts with physicians under PPOs, as well as utilization

management programs, that would allow them to grow if and when the market

shifts away from HMOs. PPOs may be less susceptible to large-scale disruptions

from provider pushback because they rely on individual contracts with physicians. ith PacifiCare under duress, the pole position among Orange County health

plans appears to be shifting to Kaiser, which has grown steadily over the past five

years to more than 300,000 enrollees. Kaiser has bounced back from the financial

stress and capacity problems that were evident in 1998. Furthermore, it has

escaped—and, indeed, benefited from—provider network stability issues because

of its group-model structure built around an exclusive relationship with a single

large medical group and affiliated hospitals. Kaiser reportedly is ahead of its competitors

in its use of disease management initiatives and Web-based communications

with consumers, in part because members stay with the health plan for an average

of 12 years.

Other health plans may benefit from shifts and uncertainty in Orange County’s

health insurance market. Some health plans that already offer PPOs—such as

Wellpoint’s Blue Cross of California, Blue Shield of California, CIGNA and Aetna—

may be more agile in the changing health plan market. These plans have developed

individual, nonrisk contracts with physicians under PPOs, as well as utilization

management programs, that would allow them to grow if and when the market

shifts away from HMOs. PPOs may be less susceptible to large-scale disruptions

from provider pushback because they rely on individual contracts with physicians.

Back to Top

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Orange County Community Report:

Aaron Katz, University

of Washington

Robert E. Hurley, Virginia Commonwealth University

Leslie Jackson,

HSC

Timothy K. Lake, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Ashley C. Short, HSC

Paul B. Ginsburg, HSC

Joy M. Grossman, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|