Word of Mouth and Physician Referrals Still Drive Health Care Provider Choice

HSC Research Brief No. 9

December 2008

Ha T. Tu, Johanna Lauer

Sponsors of health care price and quality transparency initiatives often identify all consumers as their target audiences, but the true audiences for these programs are much more limited. In 2007, only 11 percent of American adults looked for a new primary care physician, 28 percent needed a new specialist physician and 16 percent underwent a medical procedure at a new facility, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Among consumers who found a new provider, few engaged in active shopping or considered price or quality information—especially when choosing specialists or facilities for medical procedures. When selecting new primary care physicians, half of all consumers relied on word-of-mouth recommendations from friends and relatives, but many also used doctor recommendations (38%) and health plan information (35%), and nearly two in five used multiple information sources when choosing a primary care physician. However, when choosing specialists and facilities for medical procedures, most consumers relied exclusively on physician referrals. Use of online provider information was low, ranging from 3 percent for consumers undergoing procedures to 7 percent for consumers choosing new specialists to 11 percent for consumers choosing new primary care physicians.

- How Many Consumers Need to Shop for Health Care Providers?

- Word of Mouth, Physician Referrals Dominate

- Consumer Use of Price and Quality Information Remains Modest

- What Factors Matter Most to Shoppers?

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source and Funding Acknowledgement

How Many Consumers Need to Shop for Health Care Providers?

![]() onsumer-directed health care is premised on the notion that consumers faced with substantial cost-sharing requirements will be motivated and knowledgeable enough to shop for the best value in health care, taking both price and quality into account when choosing providers and treatment options. In addition to many insured consumers facing increased cost sharing, large numbers of uninsured Americans face even heavier out-of-pocket medical costs.

onsumer-directed health care is premised on the notion that consumers faced with substantial cost-sharing requirements will be motivated and knowledgeable enough to shop for the best value in health care, taking both price and quality into account when choosing providers and treatment options. In addition to many insured consumers facing increased cost sharing, large numbers of uninsured Americans face even heavier out-of-pocket medical costs.

Despite growing incentives for at least some consumers to shop and numerous public and private initiatives aimed at providing price and quality information, most consumers still rely on physician referrals and word-of-mouth recommendations from family and friends when choosing health providers, according to findings from HSC’s nationally representative 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey (see Data Source). Few consumers used price and quality information or online information sources to choose providers.

Sponsors of price and quality transparency initiatives often identify their target audiences as all consumers—or, in the case of programs sponsored by state governments, all state residents. However, the true consumer audiences for such initiatives are much more limited. When measuring the universe of consumers potentially shopping for health care providers, it is important to establish how many consumers need new primary care physicians, specialists or medical facilities for procedures during a given time. These estimates can be used to approximate the size of target markets for price and quality transparency initiatives. The findings presented in this study may be somewhat conservative estimates of the total number of shoppers because children are excluded from the estimates.

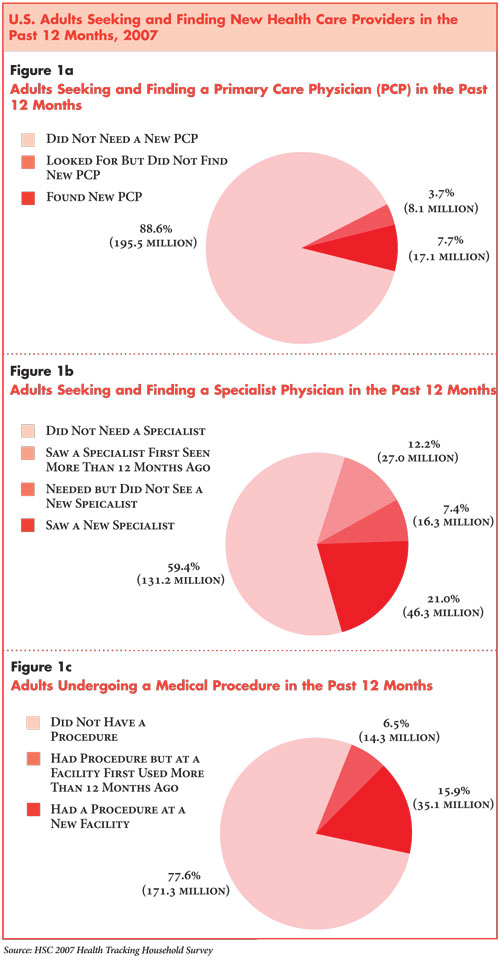

Approximately 25 million adults—more than one in 10 adults—reported looking for a new primary care physician at some point in the previous 12 months (see Figure 1a). Seventeen million of these adults found a new primary care physician, while the remaining 8 million did not.1

More consumers reported needing new specialists than primary care physicians in the previous year. Almost 63 million adults—nearly three in 10—said they needed a new specialist in the previous year, with 46 million actually seeing a new specialist (see Figure 1b).

About 35 million adults—nearly one in six—reported undergoing a medical procedure at a new facility in the past year (see Figure 1c).2 This figure included both inpatient and outpatient facilities and both surgical and nonsurgical procedures; consumers were not asked to identify the exact procedure they underwent. Approximately 19 million, or nearly 9 percent of all adults, had their procedures performed at hospitals rather than other settings, such as physician offices or ambulatory surgery centers.

Overall, adults reported needing new specialists or facilities for medical procedures more often than they needed new primary care physicians. However, it would be very challenging, if not impossible, to provide consumers with information encompassing all the types of specialists and facilities for procedures that they might need. As a result, most quality transparency programs, for instance, have focused on reporting only the most common specialties and on hospital-based procedures.

The rest of this study focuses on the consumers who actually found new primary care physicians and specialists and underwent procedures at new facilities, referring to these consumers as “shoppers,” regardless of whether they actively shopped for providers.

Back to Top

Word of Mouth, Physician Referrals Dominate

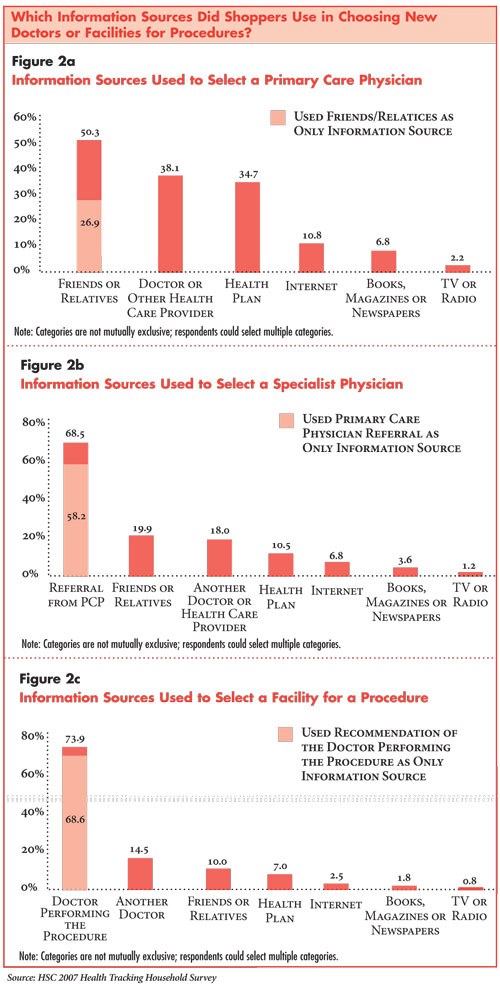

![]() mong the 17 million adults who found a new primary care

physician in the past year, half relied on recommendations from friends and

relatives, and more than one in four used such recommendations as their only

information source (see Figure 2a). This reliance on word

of mouth is consistent with previous research,3 some of

which suggests that consumers trust recommendations from friends and family

more than other sources, such as provider report cards.4

mong the 17 million adults who found a new primary care

physician in the past year, half relied on recommendations from friends and

relatives, and more than one in four used such recommendations as their only

information source (see Figure 2a). This reliance on word

of mouth is consistent with previous research,3 some of

which suggests that consumers trust recommendations from friends and family

more than other sources, such as provider report cards.4

Although word of mouth was the most commonly used information source for primary care physician selection, sizable minorities of primary care physician shoppers also used recommendations from doctors or other health care providers (38%) and information supplied by their health plans (35%). The Internet was consulted by only about one in nine shoppers. About 37 percent of primary care physician shoppers used multiple sources of information. Younger and more-educated consumers were more likely to use the Internet and to use multiple information sources in choosing primary care physicians.5

Patterns of specialist and procedure shopping differed markedly from those for primary care physician shopping. The dominant source used by consumers to find a specialist was referrals from primary care physicians: Almost seven in 10 specialist shoppers used this source, and almost six in 10 relied exclusively on this source (see Figure 2b). One in five specialist shoppers used recommendations from friends and relatives, and only 15 percent used multiple sources of information. People with chronic conditions and those in fair or poor health were more likely to rely solely on their primary care physicians’ referrals, while younger and more-educated consumers were more likely to turn to other sources, including the Internet and health plan information.

In choosing facilities for procedures, consumers were even more reliant on physician guidance. Nearly three in four consumers who had procedures relied on the recommendation or referral of the physician performing the procedure; almost all of these consumers used no other source of information (see Figure 2c). Alternative information sources were used by relatively few consumers, and only one in 12 procedure shoppers used multiple information sources when choosing a facility. Older shoppers and those with chronic conditions were more likely to rely solely on their physicians’ referrals or recommendations in choosing a facility for a procedure.

It is not surprising that consumers rely more on word of mouth when choosing primary care physicians than when choosing specialists or facilities for procedures. Since most people have a regular primary care physician, it is relatively easy to find friends and family who can recommend such a doctor. However, finding a friend or relative who has visited a certain type of specialist or undergone a particular procedure is more difficult—hence the overwhelming reliance on physician referrals. In addition, seeing a specialist or undergoing a procedure may often be associated with a more serious medical event, making consumers more inclined to rely on professional expertise. And, some health maintenance organizations (HMOs) require a primary care physician referral before an enrollee can see most types of specialists. HMO enrollees also may be required to have their procedures performed at specific facilities—thereby reducing consumers’ choices and making them less likely to consult information sources other than their doctors.

Back to Top

Consumer Use of Price and Quality Information Remains Modest

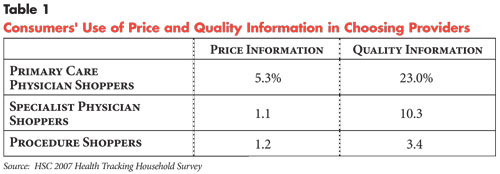

![]() ew of the consumers who needed new providers reported using

either price or quality information in choosing those providers (see Table

1). Use of price information was extremely rare across all types of shoppers.

This may reflect the scarcity of publicly available price information that consumers

find relevant and usable.6 In addition, limited use of

price information likely reflects the fact that most insured consumers have

little or no financial incentive to compare provider prices because their out-of-pocket

expenses stay constant across in-network providers.7

ew of the consumers who needed new providers reported using

either price or quality information in choosing those providers (see Table

1). Use of price information was extremely rare across all types of shoppers.

This may reflect the scarcity of publicly available price information that consumers

find relevant and usable.6 In addition, limited use of

price information likely reflects the fact that most insured consumers have

little or no financial incentive to compare provider prices because their out-of-pocket

expenses stay constant across in-network providers.7

Self-reported use of quality information was low among specialist and procedure shoppers but was higher (23%) for primary care physician shoppers. The survey did not ask respondents to specify the exact types of price or quality information used, so it is possible—even likely—that some consumers considered favorable recommendations from health care providers or friends and relatives to be “quality information.” Previous research suggests that most consumers do not believe clinical quality varies significantly across doctors, hence the low consumer demand for clinical quality report cards.8 At the same time, most consumers care about finding doctors who listen well and have an approachable and compassionate manner—the type of information they can obtain from friends and family.9 To the extent that primary care physician shoppers are treating such anecdotal patient-experience reports as quality information, the estimate of quality-information use for primary care physician shopping may be overstated.

Back to Top

What Factors Matter Most to Shoppers?

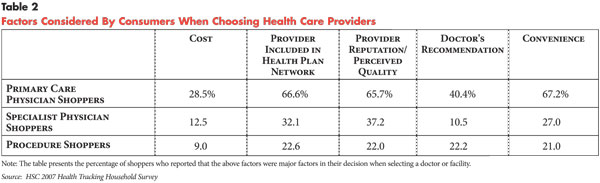

![]() onsumers were asked about various factors—cost, insurance

coverage, perceived quality (including provider reputation), doctor recommendation

and convenience—that they considered in choosing new doctors or facilities

for procedures. Regardless of the type of provider they were seeking, consumers

placed approximately equal weight on perceived quality, convenience factors

(including location and short waits for appointments) and inclusion of the provider

in their health plan network as major factors in choosing particular providers

(see Table 2).

onsumers were asked about various factors—cost, insurance

coverage, perceived quality (including provider reputation), doctor recommendation

and convenience—that they considered in choosing new doctors or facilities

for procedures. Regardless of the type of provider they were seeking, consumers

placed approximately equal weight on perceived quality, convenience factors

(including location and short waits for appointments) and inclusion of the provider

in their health plan network as major factors in choosing particular providers

(see Table 2).

Cost concerns trailed most other factors by a wide margin—again, likely a reflection of the fact that most insured consumers face no out-of-pocket cost differences when choosing among in-network providers. Indeed, uninsured shoppers were more than twice as likely as their insured counterparts to cite cost as a major factor in selecting providers. Young and low-income consumers also were substantially more likely to consider cost a major concern. Consumers with higher education levels were more likely to cite quality-related considerations, including provider reputation.

One striking pattern is that every single factor was cited much less often by specialist and procedure shoppers than primary care physician shoppers. Even though physician referrals were their dominant information source in selecting providers, specialist and procedure shoppers were much less likely than primary care physician shoppers to cite doctor recommendations as a major factor in their provider selection process. These patterns may reflect a tendency on the part of many consumers to regard the selection of primary care physicians as a more active process—one that requires them to consciously consider such priorities as provider reputation and convenience—while the selection of specialists and facilities for procedures may not be regarded as an active choice by many consumers.

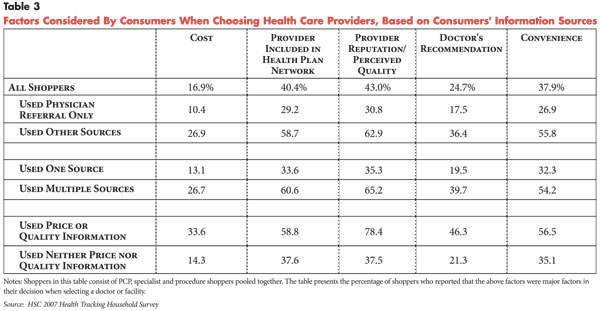

Shoppers who relied only on one information source, as well as those who relied solely on their doctor’s referral, were much less likely to report considering any other factors in choosing a provider—be it cost, quality, insurance coverage or convenience (see Table 3). This finding highlights the relative passivity of shoppers who did not use alternative or multiple information sources. For such shoppers, provider selection may be similar to filling prescriptions—simply carrying out their doctors’ instructions.

Back to Top

Implications

![]() he consumer-directed health care vision of consumers actively shopping is far removed from the reality of how most consumers currently choose health care providers. Few consumers make use of Internet information sources or price and quality information. Most still rely on the traditional sources of physician referrals or word-of-mouth recommendations from friends and family.

he consumer-directed health care vision of consumers actively shopping is far removed from the reality of how most consumers currently choose health care providers. Few consumers make use of Internet information sources or price and quality information. Most still rely on the traditional sources of physician referrals or word-of-mouth recommendations from friends and family.

One powerful impediment to active shopping may be a shortage of providers in some geographic markets or particular health plan networks. For example, consumers seeking a new primary care physician may find very few primary care physicians within a convenient distance who are actually accepting new patients. Similarly, some health plan networks may include only one specialist or subspecialist of a certain type in a given market. Consumers faced with such constraints have limited opportunities to shop.

Even when choice of providers is not constrained, there remain other impediments to shopping. This study shows that passive shoppers—those who did not use independent or multiple information sources—considered fewer factors before selecting a provider and may not regard provider selection as a choice at all. Passive shoppers, even if supplied with accurate and usable price and quality information, may be unlikely to use such information unless given compelling reasons to do so.

The most compelling reason to use price information would be strong out-of-pocket cost differentials for consumers depending upon the providers they chose. Currently, such incentives are weak or absent for most insured consumers when they stay within their health plan’s provider network.

On the quality side, consumers would likely feel more compelled to use quality information if they believed that quality differed substantially across providers, and that these differences can have concrete, serious—even life-or-death—consequences.10 For policy makers seeking to engage consumers in provider shopping and quality improvement efforts, a critical challenge is to educate consumers about the existence and the serious implications of provider quality gaps.

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Data Source

This Research Brief presents findings from the HSC 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey, which was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and conducted between April 2007 and January 2008. The overall sample size for the nationally representative survey was 18,000 people in 9,400 families. The sample size for this study was approximately 13,500 adults. The survey response rate was 43 percent. Samples were drawn using random-digit dialing techniques, and interviews were conducted by telephone using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) methods. The Household Survey module on consumer shopping for providers is available upon request from the authors.

Funding Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the California HealthCare Foundation.

Back to Top

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org