Managed Care Redux: Health Plans Shift Responsibilities to Consumers

Issue Brief No. 79

March 2004

Debra A. Draper, Gary Claxton

| Errata: An error was found in Issue Brief No. 79, Managed Care Redux: Health Plans Shift Responsibilities to Consumers, after the report’s release. On page 2, we incorrectly reported that OualChoice health plan in Little Rock, Ark., had reinstated prior-authorization requirements for MRI and CAT scans. The online documents were corrected to reflect the change on Feb. 18, 2005. |

- Plan Product Strategies Shift Responsibilities to Consumers

- Targeted Managed Care

- Plans Focus on High-Cost Patients

- Consumer Involvement

- Helping Consumers Navigate

- Are Consumers Ready?

- Notes

- Data Source

Plan Product Strategies Shift Responsibilities to Consumers

![]() n 2003, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums rose

an average of nearly 14 percent, the largest increase since 1990 and the third

straight year of double-digit increases.1 Faced with employers seeking premium

relief and consumer demands for broad choice, health plans are under pressure

to identify new ways to slow escalating premium trends while tempering consumer

discontent, according to findings from HSC’s 2002-03 site visits to 12 nationally

representative communities (see Data Source). In collaboration with employers,

plans are redeploying some traditional managed care practices, albeit with a

more targeted focus on high-cost services and patients, and developing new products

to encourage consumers to make more cost-conscious health care choices.

n 2003, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums rose

an average of nearly 14 percent, the largest increase since 1990 and the third

straight year of double-digit increases.1 Faced with employers seeking premium

relief and consumer demands for broad choice, health plans are under pressure

to identify new ways to slow escalating premium trends while tempering consumer

discontent, according to findings from HSC’s 2002-03 site visits to 12 nationally

representative communities (see Data Source). In collaboration with employers,

plans are redeploying some traditional managed care practices, albeit with a

more targeted focus on high-cost services and patients, and developing new products

to encourage consumers to make more cost-conscious health care choices.

Back to Top

Targeted Managed Care

![]() n the early and mid-1990s, managed care plans—in

response to employers’ desires to slow rapidly rising health care costs—limited

patients’ choice of physicians and hospitals, required prior approval for certain

high-cost services and restricted physicians’ clinical authority.

n the early and mid-1990s, managed care plans—in

response to employers’ desires to slow rapidly rising health care costs—limited

patients’ choice of physicians and hospitals, required prior approval for certain

high-cost services and restricted physicians’ clinical authority.

But consumers disliked restrictions on their care, prompting a powerful backlash. Competing to attract and retain workers in a tight labor market during the economic boom of the late 1990s, many employers moved away from insurance coverage with limited provider choice and extensive care restrictions. Many health plans expanded provider networks and eased restrictions on care by eliminating primary care physician (PCP) gatekeeping and prior approvals for specialty referrals and many tests and procedures.

During HSC’s 2000-01 site visits, plans in the 12 communities reported no major changes in utilization as a result of the relaxation of utilization management controls.2 By 2002-03, however, many plans had changed their assessment, and some had reintroduced administrative controls on care use. In Little Rock, for example, QualChoice reported that after eliminating prior-authorization requirements for computed axial tomography (CAT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, utilization rates doubled. According to one plan executive, "The mere fact that physicians had to justify why they were doing something helped to control unnecessary utilization."

Similarly, Aetna in northern New Jersey eliminated many prior-authorization requirements, but utilization reportedly "increased off the wall." While Aetna reinstated some requirements, plans across the 12 communities expressed little interest in returning to blanket pre-authorization requirements. Instead, plans are focusing on services that are high-cost or at high risk for inappropriate use. Some targeted services include outpatient surgery, plastic surgery, diagnostic imaging, chiropractic care and physical therapy. Likewise, plans are increasing patient cost-sharing requirements for services that tend to be more discretionary and prone to overuse.

Plans also continue to move away from PCP gatekeeping, giving consumers more liberal access to a wider range of services and providers. In Phoenix, for example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona eliminated gatekeeping requirements by moving all of its health maintenance organization (HMO) members to open-access products. Group Health Cooperative in Seattle also eliminated PCP gatekeeping requirements in its group model HMO, and now these members can see specialists in the group without a referral. At the same time, the plan instituted same-day primary care appointments to encourage members to see their PCPs first.

One exception to the general rollback of utilization management tools has been in plans serving Medicaid enrollees. These plans have largely retained prior authorization, primary care gatekeeping and other restrictions associated with traditional HMO products. The retention of these tools, in part, reflects Medicaid requirements that sharply limit beneficiary cost sharing. However, it also reflects the often low, fixed payment rates in Medicaid that require more aggressive management to contain costs related to volume; state purchaser preferences for tight controls; participating plans’ belief in the effectiveness of these tools for Medicaid enrollees; and, the weak political clout of low-income patients.3

Plans serving the privately insured also continue to manage pharmacy benefits aggressively, most prominently through the use of increased patient cost sharing. Increasingly, plans are instituting priorauthorization requirements for drugs that are both expensive and prone to misuse, such as Viagra and OxyContin. In most of the 12 communities, there is extensive use of tiered-pharmacy arrangements—three-tier and, increasingly, four-tier—which were introduced during the mid-1990s. Plans have been especially aggressive with increasing the copayment amounts in these tiered arrangements, and purchasers have been relatively supportive because these higher copayments help offset premium increases.

Four years ago, a typical three-tier pharmacy copayment design was $5 for generics, $10 for preferred brand names and $15 for nonpreferred brand names. Now, plans have doubled or even tripled these amounts or replaced copayments with coinsurance, where patients pay a percentage of the total cost.Moreover, out-of-pocket maximums that typically exist for medical services tend not to apply to pharmacy cost sharing. Across the 12 communities, plans and purchasers believe that the financial incentives associated with these tiered-pharmacy designs have been instrumental in engaging consumers more actively in drug purchasing decisions and, as a result, are shifting usage to lower cost generic drugs.

Back to Top

Plans Focus on High-Cost Patients

![]() ather than focusing on traditional managed

care practices that affect many members,

such as prior-authorization requirements for

a broad range of services, plans are instead

ramping up care management for the small

percentage of members that use a disproportionate

share of resources. Disease management

is one approach plans are actively using

across product platforms ranging from more

restrictive HMO products to more loosely

managed preferred provider organization

(PPO) products. Disease management programs

require active patient engagement and

emphasize self-care, self-management and

monitoring, and self-education.

ather than focusing on traditional managed

care practices that affect many members,

such as prior-authorization requirements for

a broad range of services, plans are instead

ramping up care management for the small

percentage of members that use a disproportionate

share of resources. Disease management

is one approach plans are actively using

across product platforms ranging from more

restrictive HMO products to more loosely

managed preferred provider organization

(PPO) products. Disease management programs

require active patient engagement and

emphasize self-care, self-management and

monitoring, and self-education.

Plans typically offer disease management programs that focus on conditions such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension, depression, cardiovascular disease and high-risk pregnancies, where proactive and timely intervention may result in delayed progression of the disease, better health outcomes, and/or lower overall costs.4 Plans sometimes offer incentives to members to encourage participation. In Cleveland, for example, Medical Mutual of Ohio waives patient copayments on diabetic supplies for members who enroll in its diabetes disease management program.

While disease management programs appear to be a potentially promising approach to working more closely with patients to better manage their health, there is limited evidence of the impact of these activities on service use, cost and quality.

Another approach that plans are using to engage patients in the management of their care is intensive case management programs, which use highly individualized care coordination for high-risk patients with multiple or complex medical conditions—typically patients most at risk for hospitalizations and other potentially costly care.5

Increasingly, plans are using predictive modeling programs as a more systematic way of identifying high-risk members in need of more intensive care management. These modeling programs typically use a scoring system that predicts members’ expected health care costs over a designated time with the specific intervention. For example, a member with a score indicating a low level of acuity may receive educational mailings; members with a score indicating a high level of acuity may receive more intensive intervention through disease management and/or case management activities.

Back to Top

|

Consumer Involvement

![]() ealth plans are developing new products

that provide consumers with significant

control over how they access and use

health care. Plans also are encouraging

more consumer involvement in weighing

the costs and benefits of those decisions.

Products going the farthest down this road

are the consumer-driven products, which

combine a personal health care spending

account with a high-deductible health

plan.6 While plans across most of the 12

communities report developing consumerdriven

products, many have proceeded

slowly with the marketing and sale of these

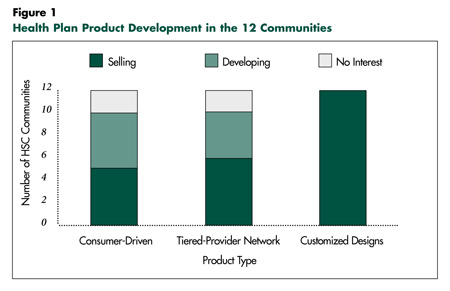

products (see Figure 1). Indeed, for plans

that have launched consumer-driven products,

take-up rates by employers are quite

small. For employers purchasing these

products as one of several product options

offered, there also has been limited take up

by employees.

ealth plans are developing new products

that provide consumers with significant

control over how they access and use

health care. Plans also are encouraging

more consumer involvement in weighing

the costs and benefits of those decisions.

Products going the farthest down this road

are the consumer-driven products, which

combine a personal health care spending

account with a high-deductible health

plan.6 While plans across most of the 12

communities report developing consumerdriven

products, many have proceeded

slowly with the marketing and sale of these

products (see Figure 1). Indeed, for plans

that have launched consumer-driven products,

take-up rates by employers are quite

small. For employers purchasing these

products as one of several product options

offered, there also has been limited take up

by employees.

Another new product, tiered-provider networks, replaces the network restrictions common in tightly managed care plans with financial incentives that encourage patients to use more cost-efficient providers. There is considerable interest in most of the 12 communities in developing tiered-provider network products, and they are currently available in Boston,Miami, northern New Jersey, Orange County, Seattle and Syracuse.7 Similar to consumer-driven products, employer and employee take-up rates for tiered-provider networks remain small in most instances.

Health plans also are developing customized product approaches that provide employers and consumers with more limited and structured choices over benefit design and out-of-pocket costs. One fairly common approach in the 12 communities is multiple-option products that permit employees to choose among defined cost sharing and benefit options after their employer has chosen a core set or level of benefits. For example, in Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield’s version of this approach, called Anthem By Design, employers select a core level of benefits, and employees can opt to upgrade benefits for additional cost. In Phoenix, HealthNet allows employers to select one of three PPO products and then employees have an option to pay more for an enhanced product. Similarly, Humana’s SmartSuite, which is available to employers with more than 50 employees in Phoenix, allows employers and their employees to choose from a variety of options, including deductible levels and copayment amounts.8 The appeal of these products is that they offer employers some control over the cost of the options, while giving employees choices that typically come with higher cost-sharing requirements.

Back to Top

Helping Consumers Navigate

Aetna, for example, offers Internet access to information on the average costs of 35 standard health care procedures to members in its HealthFund consumerdirected product. The plan also is adding provider-specific information on procedure volume and outcomes. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida, which introduced a suite of consumer-driven health plan designs in 2003, provides access to an online information system through an external vendor, HealthDialog, which gives members access to clinical information on diagnoses and treatment alternatives, linked with a telephone advice line for more specific information.

Vendors like Subimo are assisting some health plans to adopt information systems that provide enrollees with hospital-specific information on volume, outcomes and quality for specific conditions and procedures. Although plans are investing heavily in these tools, they are, for the most part, still relatively underused and of indeterminate value and will require additional development to be of significant benefit to consumers.

Back to Top

Are Consumers Ready?

![]() learly, health plans, with the support of

employers, are redeploying some utilization

management techniques and shifting more

financial and care management responsibilities

to consumers. In fact, the success of plans’

current product strategies is largely dependent

on consumers becoming more cost-conscious

health care users. Plans are hedging their bets

by adding new products to their portfolios and

by refocusing many of their existing utilization

and care management practices to position

themselves strategically should this new

"consumer-empowerment"movement take off.

learly, health plans, with the support of

employers, are redeploying some utilization

management techniques and shifting more

financial and care management responsibilities

to consumers. In fact, the success of plans’

current product strategies is largely dependent

on consumers becoming more cost-conscious

health care users. Plans are hedging their bets

by adding new products to their portfolios and

by refocusing many of their existing utilization

and care management practices to position

themselves strategically should this new

"consumer-empowerment"movement take off.

Some plans in the 12 communities believe that this shift toward consumers is where markets are headed; others are less optimistic but want to be well positioned, just in case. In combination with increased consumer responsibility, plans hope that targeted utilization management can reduce inappropriate care without alienating consumers, help curb costs and lessen the rate of premium increases passed on to employers.However, the collective effect of these strategies on costs is not currently known, although, for now, it is likely to be small.

The appetite of consumers to take on new financial and care management responsibilities is unclear at present. Some of the ambiguity lies in the fact that plans have only recently developed many of these new product arrangements, so current sales and take-up rates are limited. Consumers, however,may need more incentives to move in the direction plans and employers are hopeful they will go. Financial incentives in the form of premium breaks or more targeted cost sharing, for example, might encourage more rapid consumer engagement. Additionally, heightened health plan accountability may be needed to make sure consumers have adequate decisionsupport tools to aid them with their new responsibilities. Ultimately—even with appropriate tools and incentives—it is unclear whether consumers will embrace greater financial and care management responsibility as a fair trade-off for fewer restrictions on access to care.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | Gabel, Jon, et al., "Health Benefits in 2003: Premiums Reach Thirteen-Year High as Employers Adopt New Forms of Cost Sharing," Health Affairs,Vol. 22, No. 5 (September/October 2003). |

| 2. | Draper, D., R. Hurley, C. Lesser and B. Strunk, "The Changing Face of Managed Care," Health Affairs,Vol. 21, No. 1 (January/February 2002). |

| 3. | Draper, D., R. Hurley and A. Short,"Medicaid Managed Care: The Last Bastion of the HMO Product?," Health Affairs,Vol. 23, No. 2 (March/April 2004). |

| 4. | Short, A., G. Mays and J. Mittler, Disease Management: A Leap of Faith to Lower-Cost, Higher Quality Health Care, Issue Brief No. 69, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (October 2003). |

| 5. | Ibid. |

| 6. | For additional description of these types of products, see for example, Christianson, J., S. Parente and R. Taylor, "Defined-Contribution Health Insurance Products: Development and Prospects," Health Affairs,Vol. 21, No. 1 (January/February 2002). |

| 7. | Mays, G., G. Claxton and B. Strunk, Tiered-Provider Networks: Patients Face Cost-Choice Trade-Offs, Issue Brief No. 71, Center for Studying Health System Change,Washington, D.C. (November 2003). |

| 8. | Humana, Inc. http://www.humana.com/ corporatecomm/newsroom/releases/PR-News- 20020926-083544-NR.html (Sept. 26, 2002). |

Back to Top

Data Source

Every two years, HSC researchers visit 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities to track changes in local health care markets. The 12 communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. HSC researchers interviewed key individuals in each community, including representatives of health plans, providers, employers, policy makers and other stakeholders. This Issue Brief is based on an analysis of these individuals’ assessments of health plans’ evolving product strategies and the expectations concerning their impact on the role of consumers in the management of their health care.

Back to Top

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Vice President: Len M. Nichols

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser