Are Defined Contributions a New Direction for Employer-Sponsored Coverage?

Issue Brief No. 32

October 2000

Sally Trude, Paul B. Ginsburg

![]() efined contributions for health benefits are being promoted as the new silver bullet

for employers to combat the rising costs of health care, the managed care backlash

and the changing climate for employer liability. As interest in this concept grows,

so does the number of proposed alternatives for implementing it. Originally called

fixed contributions, defined contributions now also refer to cash transfers or vouchers,

with reliance on the individual market for health insurance. A more recent angle for

defined contributions is using the Internet as an on-line marketplace for purchasing

health insurance. This Issue Brief examines defined-contribution strategies and

assesses issues relevant to employers, employees and public policy makers.

efined contributions for health benefits are being promoted as the new silver bullet

for employers to combat the rising costs of health care, the managed care backlash

and the changing climate for employer liability. As interest in this concept grows,

so does the number of proposed alternatives for implementing it. Originally called

fixed contributions, defined contributions now also refer to cash transfers or vouchers,

with reliance on the individual market for health insurance. A more recent angle for

defined contributions is using the Internet as an on-line marketplace for purchasing

health insurance. This Issue Brief examines defined-contribution strategies and

assesses issues relevant to employers, employees and public policy makers.

Why Defined Contributions?

![]() he renewed interest in a defined-contribution approach to

health benefits has been inspired by the changing approach to pension benefits.

For retirement benefis, the employer contributes to employees’ pension accounts

based on earnings (defined contribution) instead of guaranteeing a level of

payment upon retirement (defined benefit). This increases portability of pensions

for employees who change jobs, and shifts investment risk and responsibility

from the employer to employees.

he renewed interest in a defined-contribution approach to

health benefits has been inspired by the changing approach to pension benefits.

For retirement benefis, the employer contributes to employees’ pension accounts

based on earnings (defined contribution) instead of guaranteeing a level of

payment upon retirement (defined benefit). This increases portability of pensions

for employees who change jobs, and shifts investment risk and responsibility

from the employer to employees.

Given the growing popularity of defined contributions for pensions, many benefit consultants and employers are devising similar strategies for health benefits, hoping to expand choice for employees, contain costs and relieve employers of the administrative burden of managing health benefits. Despite the growing interest, few employers have adopted defined contributions for health benefits. With a tight labor market, employers are cautious about making any changes that employees might perceive as a reduction in benefits. Also, depending on the approach taken, employers and employees could lose the benefit of tax subsidies, risk pooling and bargaining clout with insurers.

Fixed-Dollar Contribution

![]() defined contribution for health benefits was first proposed

in the late 1970s by Alain Enthoven as part of managed competition, an approach

for containing costs through greater price-based competition among health plans.

A fixed-dollar contribution toward health benefits was expected to make employees

more cost conscious because they would pay for any additional benefits beyond

the lowest-cost plan. Over time, as premiums rise, the fixed-dollar amount could

be increased to keep up with the cost of the lowest-price plan. Alternatively,

the fixed-dollar amount could be increased by the general inflation rate, so

that increases in premiums that exceed general inflation are borne by the employee.

defined contribution for health benefits was first proposed

in the late 1970s by Alain Enthoven as part of managed competition, an approach

for containing costs through greater price-based competition among health plans.

A fixed-dollar contribution toward health benefits was expected to make employees

more cost conscious because they would pay for any additional benefits beyond

the lowest-cost plan. Over time, as premiums rise, the fixed-dollar amount could

be increased to keep up with the cost of the lowest-price plan. Alternatively,

the fixed-dollar amount could be increased by the general inflation rate, so

that increases in premiums that exceed general inflation are borne by the employee.

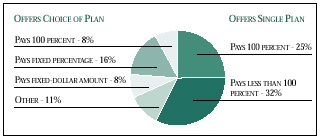

Since that time, most employers have begun offering managed care plans, but relatively few adopted a fixed-dollar contribution strategy. According to The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, a component of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) Community Tracking Study, only 8 percent of employees who are offered health insurance have a choice of plans with a fixed-dollar contribution (see Figure 1).

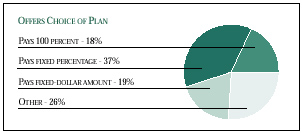

Adopting a fixed-contribution approach requires employers to offer a choice of health plans, which increases the cost and administrative burden of offering health insurance. Even among those employees who are offered a choice of health plans, only 19 percent have a fixed-dollar contribution paid toward their premium (see Figure 2). In contrast, 18 percent of employees have the entire premium for each plan offered paid by their employer, while another 37 percent have a fixed percentage of their premium covered.

Employers who pay a substantial share of the premium may be limited in their ability to set the contribution rate no higher than the premium of the lowest-price plan. In a tight labor market or with a unionized workforce, these employers may be reluctant to reduce their benefits. For example, the fixed-dollar contribution for state employees covered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), which is subject to collective bargaining, exceeds the premiums for many of the plan offerings. As a result, CalPERS employees have several plan offerings available at no cost, with a limited incentive to pick the lowest-price plan. To avoid this, employers offer a cafeteria plan, which allows their employees to apply those savings to other benefits, such as vision or dental.

A fixed-dollar approach increases employers’ need to limit adverse selection. For example, employers can design their benefit offerings and choose plans to avoid having older or sicker workers select one plan while healthy young families select another, or they can offer a selection of plans that do not differ substantially in cost or quality. If adverse selection does occur, employers can readjust their choice of plans or benefit offerings or risk adjust payments, paying plans different amounts for different categories of employees. Health plans also seek to minimize adverse selection through their premiums and product design and by limiting some employers to a single carrier.

Finally, under a fixed-dollar approach, employers must provide adequate information for employees to compare the quality of health plans so they can choose one based on value, not just on cost. This can be expensive and especially difficult for some employers. National companies must collect information across many markets, while smaller companies may not have the staff resources.

Figure 1

Percent of Employees by Contribution Policy of Companies

Offering Insurance

Source: 1997 RWJF Employer Health Insurance Survey

Figure 2

Percent of Employees by Contribution Policy of Companies

Offering a Choice of Plans

Source: 1997 RWJF Employer Health Insurance Survey

Cash Transfers or Vouchers

![]() ecently, defined contributions have been proposed as a way

for employers to step out of the role of health purchaser. Emulating defined

contributions for pension benefits, proponents recommend transferring the risk

and responsibility for health benefits to the employee. To do so, employers

would pay their employees higher wages, and employees could purchase their health

insurance in the individual market. Employers would eliminate the costs and

hassles involved in managing health benefits, and remove themselves from the

firing line of employees’ grievances with health plans. Xerox sparked some controversy

last year when it discussed such a strategy.

ecently, defined contributions have been proposed as a way

for employers to step out of the role of health purchaser. Emulating defined

contributions for pension benefits, proponents recommend transferring the risk

and responsibility for health benefits to the employee. To do so, employers

would pay their employees higher wages, and employees could purchase their health

insurance in the individual market. Employers would eliminate the costs and

hassles involved in managing health benefits, and remove themselves from the

firing line of employees’ grievances with health plans. Xerox sparked some controversy

last year when it discussed such a strategy.

Some critics suggest that this cash approach is tantamount to not offering insurance. Both employers and employees would lose the tax advantage of having the employer’s contribution to the health insurance premium excluded from taxable income. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that this tax subsidy is roughly 26 percent of health insurance premiums, on average, although the amount of the tax subsidy varies by income.

Others have proposed vouchers, which would ensure that funds are used for health insurance and would preserve the tax advantage. Vouchers also allow employers to transfer funds directly as payroll deductions, avoiding the largeadministrative costs of collecting regular payments from individuals.

The Employee Benefit Research Institute estimates that premiums to purchase comparable insurance on the individual market would cost 32 percent more for employees in companies with more than 1,000 workers, and 24 percent more in medium-size companies.1 Given the tight labor market, employers adopting cash transfers or vouchers would have to pay a large offset to compensate for any loss of the tax subsidy and the higher costs of health insurance in the individual market.

If employers adopt cash transfers or vouchers, this could end the pooling through which lower-risk employees subsidize higher-risk employees. Currently, most employees pay the same amount, regardless of their age and sex, and pay a differential only to cover their spouse and children. As a result, employees are rarely aware of payment differentials that account for the higher costs of the older worker compared to the younger worker. For example, in the individual health insurance market the premium for the same health plan product may be twice as expensive for a 50-year-old male as for a 25-year-old male. Nor are employees typically aware that those with individual coverage subsidize those with family coverage.

Employers may also find that employees resist cash transfers and vouchers because they do not want to lose the employer’s ability to advocate on their behalf. For example, in addition to negotiating premiums, employers play an important role in resolving poor customer service and employee grievances.

A recent study of employees in large firms found that the workers did not want to purchase insurance on the individual market because they valued their employers’ role in negotiating with insurers over rates and benefits, and in reducing the complexity of their choices.2 Employees who had had serious illnesses also valued their employer’s advocacy role in helping them get the full range of covered services. A 1999 national survey found that, given current tax laws, 75 percent of employees preferred to get health insurance through their employer than to receive higher wages and purchase health insurance on their own.3

Internet Innovations

![]() nternet-based ventures are poised to offer technological

strategies to more easily allow employers to implement defined-benefit approaches.

Firms such as eBenX.com and Sageo.com help employers administer their health

benefits and allow employees to choose their health plan on-line. In particular,

these firms can provide performance and provider network information customized

to the employee. For example, some employees may select plans based on customer

service and satisfaction ratings, while others may select plans based on the

availability of a particular physician.

nternet-based ventures are poised to offer technological

strategies to more easily allow employers to implement defined-benefit approaches.

Firms such as eBenX.com and Sageo.com help employers administer their health

benefits and allow employees to choose their health plan on-line. In particular,

these firms can provide performance and provider network information customized

to the employee. For example, some employees may select plans based on customer

service and satisfaction ratings, while others may select plans based on the

availability of a particular physician.

Other Internet ventures may facilitate employers’ move to defined-contribution approaches by establishing mechanisms that preserve risk pooling and tax advantages. The strategies of companies such as HealthSync and Vivius that seek to fill this niche vary substantially, however. One seeks to establish an on-line marketplace for choosing health plans, while the other would have consumers customize their own network of providers and create their own plan. It is still too early to tell whether these ventures will be successful or what new issues will arise.

Policy Implications

![]() f employers implement defined contributions, public policy

makers will be particularly interested in assessing the potential effect on

the number of uninsured persons. Cash transfers or vouchers could increase the

number of uninsured persons if employer contributions do not cover the higher

costs of insurance adequately in the individual market. Currently, 5 percent

of workers with access to employer-sponsored coverage do not enroll and are

uninsured as a result, principally because of costs. Low-wage workers are much

more likely to be uninsured because of not enrolling in plans they are eligible

for.4

f employers implement defined contributions, public policy

makers will be particularly interested in assessing the potential effect on

the number of uninsured persons. Cash transfers or vouchers could increase the

number of uninsured persons if employer contributions do not cover the higher

costs of insurance adequately in the individual market. Currently, 5 percent

of workers with access to employer-sponsored coverage do not enroll and are

uninsured as a result, principally because of costs. Low-wage workers are much

more likely to be uninsured because of not enrolling in plans they are eligible

for.4

With reliance on the individual market, some older workers or those with chronic illnesses may find that they cannot obtain or afford coverage. In addition, cash transfers may increase the number of uninsured young, healthy workers who might prefer to use their higher wages for other purposes.

On the other hand, some defined-contribution strategies may reduce the number of uninsured persons by enhancing low-wage workers’ ability to afford insurance. For example, an employer may currently cover 75 percent of a health plan with high premiums. By moving to a fixed-dollar contribution, the employer may cover the full premium of a lower-priced plan, but have employees pay more for the higher-priced plan. In this case, more low-wage workers would be likely to take up insurance. However, this lower-priced plan may have more restrictions, reduced benefits or higher deductibles. Also, employers’ efforts to minimize adverse selection through benefit design and plan selection could limit their ability to substantially reduce the employee contribution.

Some proposed reforms to improve insurance coverage for small businesses and self-employed workers could inadvertently encourage some large employers to adopt defined-contribution approaches. For example, current proposals to make tax deductions equitable for the self-employed or employees of small businesses would allow 100 percent tax deductions for health insurance purchased on the individual market. If the provision does not exclude employees of large companies, some large employers might be more likely to pursue the cash-transfer approach to defined contributions.

Finally, employers currently play an important role as advocates on behalf of their employees-for example, resolving customer service issues and disputes over coverage. Some employers also play an important role in improving the health system in general by pushing for patient safety, quality improvement and accountability. Ironically, although some employers may move toward defined contributions to sidestep the managed care backlash, erosion of employer-based coverage may intensify employees’ concerns. Therefore, a trend toward defined contributions could be accompanied by additional regulation of health plans through patient protection legislation.

Defined Contributions: How Relevant Is the Pension Approach to Health Benefits?

![]() efined contributions for pensions are attractive to employers because they

make retirement savings more portable for people who change jobs and shift responsibility

for investment decisions from employers to employees. These features apply to

health benefits as well, but two key issues do not have a parallel in the pension

world.

efined contributions for pensions are attractive to employers because they

make retirement savings more portable for people who change jobs and shift responsibility

for investment decisions from employers to employees. These features apply to

health benefits as well, but two key issues do not have a parallel in the pension

world.

One difference with health benefits is the importance of risk pools, where all employees pay the same amount for coverage, despite large differences in likely use of services. Some defined-contribution approaches would end this practice, resulting in substantial redistribution among employees and changing the population for whom insurance is affordable.

A second difference is risk selection. Because individuals who are more likely to use services are also more likely to obtain insurance and choose plans with more extensive benefits, employers and health plans limit the range of choices to avoid this adverse selection. While the defined-contribution approach to health benefits arose partly as an attempt to expand choice, the failure of insurance markets to cope with risk selection remains problematic.

Notes

1. Fronstin, Paul, Presentation to Healthcare Business Media, Inc., Employee Benefit Research Institute (May 2000). Note: Medium-sized companies have 100 to 999 employees.

2. Lave, Judith, R., et al., "Changing the Employer-Sponsored Health Plan System: The Views of Employees in Large Firms," Health Affairs, Vol. 18, No. 4 (July/August 1999).

3. Fronstin, Paul, "Employment-Based Health Insurance Remains Popular," Employee Benefit Research Institute News Brief (April 29, 1999).

4. Cunningham, Peter J., Elizabeth Schaefer and Christopher Hogan, "Who Declines Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance and Is Uninsured?" Issue Brief No. 22 (October 1999).

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group