If the Price is Right, Most Uninsured—Even Young Invincibles—Likely to Consider New Health Insurance Marketplaces

HSC Research Brief No. 28

September 2013

Peter J. Cunningham, Amelia M. Bond

A key issue for the new insurance exchanges under national health reform is whether enough younger and healthier people will take advantage of new subsidized coverage on Jan. 1, 2014. Without enough good risks to offset older and sicker people who are likely to jump at the opportunity to gain more-affordable coverage, the exchanges risk significant adverse selection—attracting a sicker-than-average population—that will drive up premiums. Key to persuading younger and healthier uninsured people to opt for coverage will be convincing them that health insurance is a good deal, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). While most uninsured people believe health insurance is important, far fewer now believe coverage is affordable and worth the cost. However, new federal subsidies for lower-to-middle-income people may change the calculus of whether coverage is affordable.

While uninsured people who are younger, have few or no health problems, and are self-described risk-takers are more likely to believe they can go without health insurance, even a majority of these so-called young invincibles believe health insurance is important. The findings indicate that most uninsured people are not inherently resistant to the idea of having health insurance. The main challenge will be to convince them that new coverage options under national health reform are affordable and offer enough protection to offset the medical and financial risks of going without health coverage.

- A New Deal for Health Insurance

- Attitudes About Health Insurance

- Makiing the Sale to Risk-Takers

- Young Invincibles vs. Older Adults

- Eligibility for ACA Coverage Expansions

- African Americans and Coverage Preferences

- State Variation in Health Insurance Preferences

- Implications for Health Reform

- Notes

- Data Source

- Supplementary Tables

- Funding Acknowledgement

A New Deal for Health Insurance

![]() he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 will make health insurance more affordable for millions of uninsured people by providing subsidies to purchase private coverage in new health insurance exchanges. Additionally, the law will assess a tax penalty—the individual mandate—on people with access to affordable coverage who choose to remain uninsured.

he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 will make health insurance more affordable for millions of uninsured people by providing subsidies to purchase private coverage in new health insurance exchanges. Additionally, the law will assess a tax penalty—the individual mandate—on people with access to affordable coverage who choose to remain uninsured.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates 24 million people will use the new health insurance exchanges by 2023 to buy subsidized private coverage under the ACA.1 However, there is great uncertainty in the near term about how many uninsured people will opt to purchase coverage starting in January 2014 when the exchanges will open for business.

A key issue for the new insurance exchanges under national health reform is whether enough younger and healthier people will take advantage of new subsidized coverage. Without enough good risks to offset older and sicker people who are likely to jump at the opportunity to gain more-affordable coverage, the exchanges risk significant adverse selection—attracting a sicker-than-average population—that will drive up premiums. Key to persuading younger and healthier uninsured people to opt for coverage will be convincing them that health insurance is a good deal.

Back to Top

Attitudes About Health Insurance

![]() ninsured people’s attitudes about health insurance will play an important role in whether and how quickly they enroll for coverage in the new exchanges. Findings from the nationally representative 2008-2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) indicate that most uninsured nonelderly adults without access to employer-sponsored coverage believe health insurance is important, but a significant minority also believes health insurance is unaffordable (see Data Source).

ninsured people’s attitudes about health insurance will play an important role in whether and how quickly they enroll for coverage in the new exchanges. Findings from the nationally representative 2008-2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) indicate that most uninsured nonelderly adults without access to employer-sponsored coverage believe health insurance is important, but a significant minority also believes health insurance is unaffordable (see Data Source).

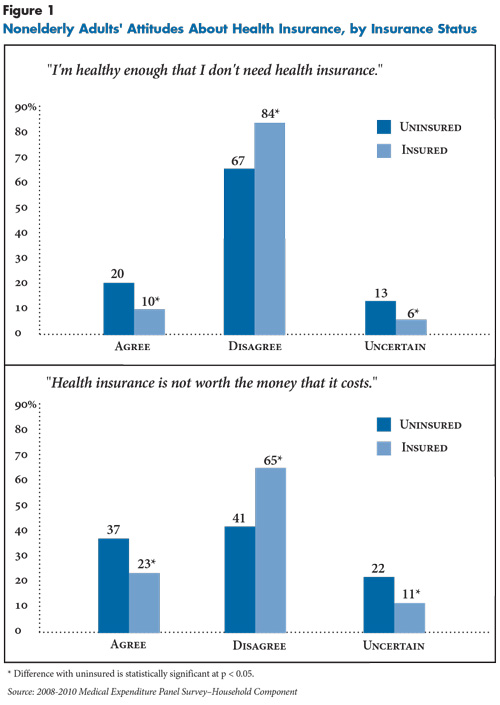

Health insurance attitudes are assessed by two questions in the MEPS that asked people to agree or disagree with the following statements: 1) “I’m healthy enough that I don’t need health insurance,” and; 2) “Health insurance is not worth the money that it costs.” Previous research indicates that responses to these questions strongly predict whether people with access to employer-sponsored coverage actually enroll in such coverage.2 Examining how uninsured adults without access to employer coverage view health insurance can offer important insights into their attitudes about coverage options in the new insurance marketplaces.

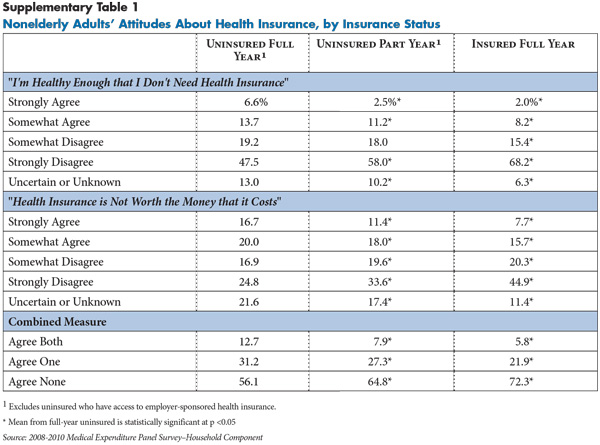

Among uninsured adults without access to employer coverage, only two in 10 believed they are “healthy enough that I don’t need health insurance,” indicating that a majority of uninsured people believe health insurance is important (see Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). However, these same uninsured people are almost evenly split in their views about whether health insurance is affordable—37 percent believe “health insurance is not worth the money that it costs,” 41 percent believe insurance is worth the cost and 22 percent are uncertain.

Although most uninsured people believe insurance is important, and a sizeable minority even believes coverage is affordable, their preferences are significantly weaker than insured people. Among insured people, more than 80 percent believe health insurance is important, and about two-thirds believe insurance is affordable. Most insured people, however, either have employer-sponsored coverage—which is heavily subsidized by employers—or Medicaid or other public coverage that usually involves little or no out-of-pocket costs.

Back to Top

Making the Sale to Risk-Takers

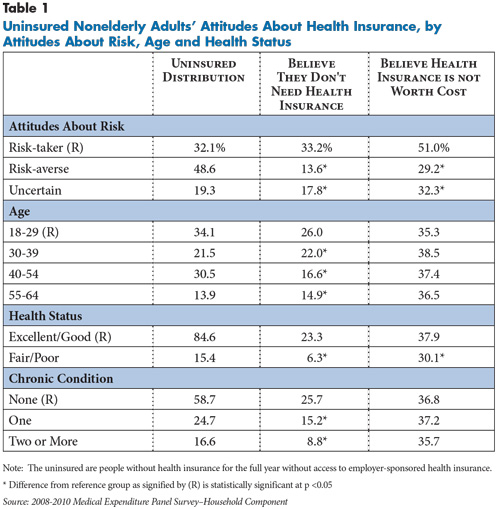

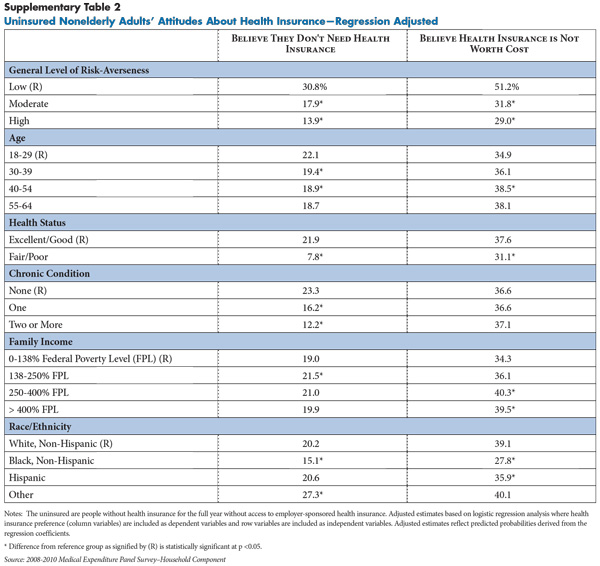

![]() onvincing uninsured people, especially those without immediate medical needs, that going without health insurance poses significant financial and medical risks and that coverage is affordable will be key to strong enrollment in the new marketplaces. How easy or difficult it is to convince people of the value of health insurance will depend in part on how predisposed they are to taking risks. The extent of risk-taking or risk-aversion is assessed in the MEPS by asking respondents whether they agree or disagree with the statement, “I’m more willing to take risks than the average person.” About one-third of uninsured nonelderly adults described themselves as risk-takers, and they are more than twice as likely to believe they do not need health insurance (33.2 %) or that it is not worth the cost (51%) compared to uninsured people who are risk-averse (see Table 1).

onvincing uninsured people, especially those without immediate medical needs, that going without health insurance poses significant financial and medical risks and that coverage is affordable will be key to strong enrollment in the new marketplaces. How easy or difficult it is to convince people of the value of health insurance will depend in part on how predisposed they are to taking risks. The extent of risk-taking or risk-aversion is assessed in the MEPS by asking respondents whether they agree or disagree with the statement, “I’m more willing to take risks than the average person.” About one-third of uninsured nonelderly adults described themselves as risk-takers, and they are more than twice as likely to believe they do not need health insurance (33.2 %) or that it is not worth the cost (51%) compared to uninsured people who are risk-averse (see Table 1).

Uninsured adults aged 18 to 29, people in good health and those with no chronic conditions also are much more likely to believe they don’t need health insurance compared to older and sicker uninsured people. However, there were fewer age and health differences in people’s assessments of whether insurance is worth the cost, possibly reflecting differences in the current cost of nongroup coverage for people of different ages and health statuses. For example, young adults generally get lower health insurance premiums in the nongroup market, but they may perceive these premiums as too costly because they tend to have lower incomes and do not believe health insurance is as important. Conversely, older adults more strongly believe in the importance of health insurance, but they often face unaffordable premiums—or are denied coverage outright—because of their age and pre-existing conditions.

Back to Top

Young Invincibles vs. Older Adults

![]() any believe that older uninsured people will be among the first and most eager to enroll in coverage given their higher prevalence of health problems, while young adults—often referred to as the young invincibles—will be reluctant to enroll because they have fewer health problems and are more willing to risk going without coverage. While there is support for this view, this study’s findings indicate health insurance attitudes are more varied and diverse than widely believed.

any believe that older uninsured people will be among the first and most eager to enroll in coverage given their higher prevalence of health problems, while young adults—often referred to as the young invincibles—will be reluctant to enroll because they have fewer health problems and are more willing to risk going without coverage. While there is support for this view, this study’s findings indicate health insurance attitudes are more varied and diverse than widely believed.

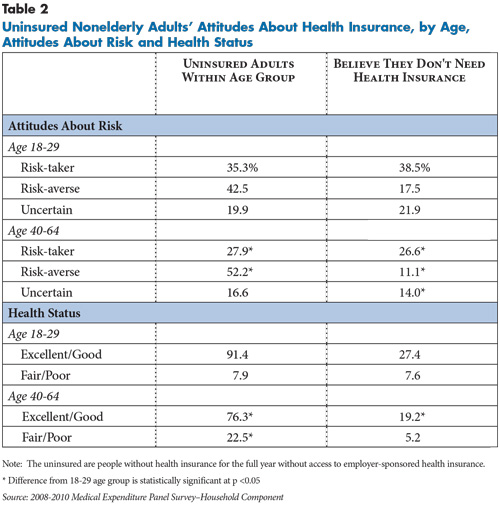

Consistent with the young-invincible view, uninsured young adults aged 18 to 29 are more likely to be risk-takers compared to older uninsured adults aged 40 to 64—35.3 percent vs. 27.9 percent, respectively (see Table 2). Among self-described risk-takers, 38.5 percent of young adults say they do not need insurance compared to 26.6 percent of older adults. And, among the 42.5 percent of young adults who described themselves as “risk-averse,” a minority (17.5%) does not believe health insurance is important.

Similarly, while more than 90 percent of young adults described their health as excellent or good, less than one in three healthy young adults (27.4%) does not believe health insurance is important. Three times as many older adults described their health as fair or poor compared to younger adults (22.5% vs. 7.9%), but more than three-fourths of older adults are in good or excellent health. And while few older adults in poor health believe that health insurance is not important, even older adults in good health have strong preferences for coverage.

In sum, most of the young invincibles apparently do not believe they are so invincible that they do not need health insurance, suggesting that well-targeted outreach and enrollment efforts may succeed in enrolling them in coverage. At the same time, even if older adults enroll at a much faster and higher rate than young adults, the view that this might lead to serious adverse selection and destabilize the exchanges might be overstated. For both groups, the key will be whether new coverage options available through the ACA will be perceived as affordable and worth the cost.

Back to Top

Back to Top

Eligibility for ACA Coverage Expansions

![]() ndividuals with family incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level will be eligible for Medicaid in states that adopt the ACA expansion. People with no access to affordable employer coverage and family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty will be eligible for sliding-scale premium subsidies to purchase private coverage through the insurance exchanges—subsidies start at 100 percent of poverty in states that do not expand Medicaid. People with family incomes greater than 400 percent of poverty will be able to purchase private insurance through the marketplaces but will not receive premium subsidies.

ndividuals with family incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level will be eligible for Medicaid in states that adopt the ACA expansion. People with no access to affordable employer coverage and family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty will be eligible for sliding-scale premium subsidies to purchase private coverage through the insurance exchanges—subsidies start at 100 percent of poverty in states that do not expand Medicaid. People with family incomes greater than 400 percent of poverty will be able to purchase private insurance through the marketplaces but will not receive premium subsidies.

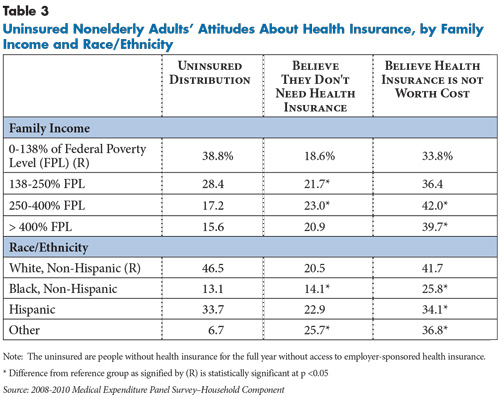

There are relatively few differences among uninsured people across these income-eligibility categories in terms of perceptions of the importance of health insurance coverage (see Table 3). Surprisingly, however, uninsured people at higher-income levels are more likely to perceive health insurance as not being worth the cost compared to uninsured people at lower-income levels. Further analysis shows that this difference is not explained by income-related differences in risk-taking, health status and age (see Supplementary Table 2). It’s possible that uninsured people at somewhat higher-income levels have more direct experience with purchasing coverage—for example, they tried but failed to obtain coverage, had to pay a surcharge because of medical underwriting, or had coverage and were forced to drop it because of costs—and therefore have more knowledge about the actual costs of private health insurance.

Back to Top

African Americans and Coverage Expansions

Back to Top

State Variation in Health Insurance Preferences

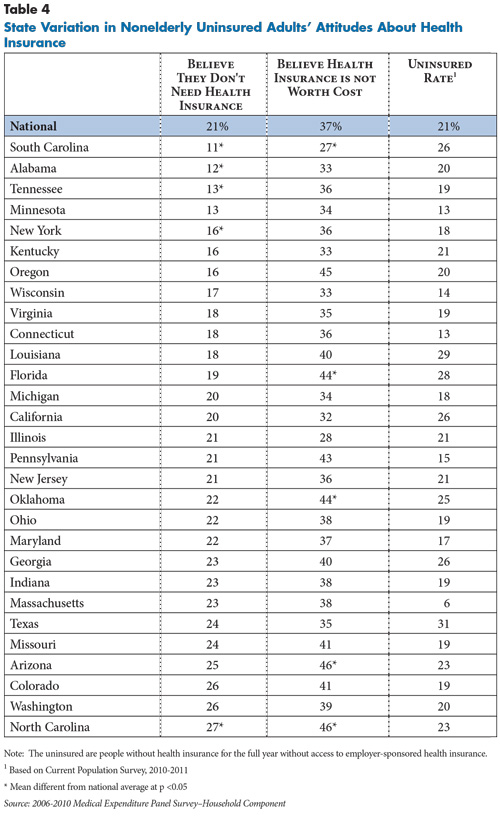

![]() here is considerable variation across states in uninsured people’s attitudes about health insurance. Among the 29 states in the MEPS that permit state-level estimates, the proportion of uninsured people who believe they do not need health insurance ranges from 11 percent in South Carolina to 27 percent in North Carolina (see Table 4). At the same time, the share of people who believe health insurance is not worth the cost ranges from 27 percent in South Carolina to 46 percent in Arizona.

here is considerable variation across states in uninsured people’s attitudes about health insurance. Among the 29 states in the MEPS that permit state-level estimates, the proportion of uninsured people who believe they do not need health insurance ranges from 11 percent in South Carolina to 27 percent in North Carolina (see Table 4). At the same time, the share of people who believe health insurance is not worth the cost ranges from 27 percent in South Carolina to 46 percent in Arizona.

It’s plausible that at least some of the state variation reflects differences in characteristics of the uninsured, especially their attitudes toward risk-taking, age, health status, family income, race/ethnicity and urban/rural residence. However, when these characteristics are accounted for, most of the state variation remains.3 Accounting for differences in the characteristics of uninsured persons explains only 11 percent of the state variation in perceptions of the importance of health insurance coverage and 4 percent of the state variation in perceptions of whether health insurance is worth the cost.4

Differences in health insurance preferences across states may reflect more systematic differences in the “culture of insurance” that aren’t reflected in individual characteristics. For example, states with higher percentages of uninsured, fewer small firms that offer coverage to employees, and with relatively low spending on Medicaid and other state coverage programs may indicate a weaker culture of insurance coverage in those states. However, when these state-level factors are examined more systematically, there was no discernible pattern regarding health insurance preferences of the uninsured. Additionally, there is little or no correlation between the size of the uninsured population in the state and preferences for health insurance among the uninsured.

On the other hand, state variation in attitudes among the insured population was strongly correlated with attitudes among the uninsured population. That is, states with weak preferences for health insurance among the uninsured population also had weak preferences for coverage among the insured population—relative to the insured population in other states. This suggests that preferences regarding health insurance reflect more generalized attitudes among the population in the state—rather than just the uninsured population—although the reasons for the state variation remain largely unexplained.

Back to Top

Back to Top

Implications for Health Reform

![]() hile people’s attitudes about health insurance captured through survey questions will not necessarily determine whether and how quickly they will enroll in coverage, prior research using the same data about health insurance attitudes showed that stronger preferences for insurance coverage were important predictors of whether people enrolled in employer-sponsored coverage.

hile people’s attitudes about health insurance captured through survey questions will not necessarily determine whether and how quickly they will enroll in coverage, prior research using the same data about health insurance attitudes showed that stronger preferences for insurance coverage were important predictors of whether people enrolled in employer-sponsored coverage.

It’s important to note that the sample for this study included uninsured people without access to employer coverage who may differ in important ways from people with access to employer coverage. Specifically, some uninsured people in this study may already have exercised a “choice” to not have coverage by declining job opportunities that come with health benefits or by declining to purchase nongroup coverage that—while expensive—was affordable if they were willing and able to make other trade-offs in their family budget. Indeed, while there are many factors that will ultimately determine how many people enroll in coverage through the exchanges, this study’s results suggest one of the most important factor will be whether people believe coverage is affordable and worth the cost.

Polls consistently show that many people eligible for coverage under the ACA expansions remain unaware or confused about the law, especially about whether they will have access to affordable coverage on Jan. 1, 2014.5 The survey questions used to assess health insurance preferences in this study were asked independent of any particular type of health coverage or health care policy and, therefore, reflect general attitudes and preferences not influenced by the ongoing debate about the ACA. This study’s findings suggest that the widely held view that the so-called young invincibles will be very difficult to enroll, and that without them, older and sicker adults will enroll in vast numbers and destabilize the health insurance marketplaces is overstated. Young adults are healthier and more willing to take risks compared to older adults, but even the majority of healthy and risk-taking young adults believe health insurance is important.

On average, older adults have stronger preferences for health coverage than younger adults, but this is true even among the majority who are in good health. Thus, even if older adults enroll faster and in larger numbers initially than young adults, it is doubtful that this will result in serious adverse selection that will destabilize the new health insurance marketplaces.

The greater challenge will be convincing uninsured people across all age and health groups that health insurance is worth the cost, and these attitudes surprisingly do not vary as much by age and health status. Whether people view the costs as reasonable will depend on their expectations—which will differ depending on their individual circumstances—as well as their eligibility for premium subsidies. The ACA will substantially increase the affordability of nongroup insurance coverage in new health insurance marketplaces through premiums subsidies that are structured so that families will not be required to spend more than between 3.3 percent of family income on premiums at the highest subsidy level (138% of poverty) to 9.5 percent of family income at the lowest subsidy level (400% of poverty). Cost-sharing subsidies—to help cover deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs—also are available for lower-income people.

While there will be tax penalties for uninsured people who fail to enroll in coverage deemed affordable, it is unclear whether this penalty will be a sufficient incentive to gain coverage, especially in the early years when the penalty is the greater of 1 percent of family income or $95 in 2014 and $325 in 2015. As the tax penalty increases—to $675 by 2016—it may become more of an inducement to enroll in coverage.

Ultimately, however, persuading uninsured people that health coverage is worth the cost may depend on convincing them of the potential medical and financial risks of going without insurance. As with other forms of insurance, including auto insurance that is legally required for car owners, there will always be people who are willing to risk going without coverage. However, this study’s results indicate that the majority of uninsured people—including young adults—believe health insurance is important and—given the right price—most are willing to consider enrolling.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | Banthin, Jessica, and Sara Masi, CBO’s Estimate of the Net Budgetary Impact of the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Coverage Provisions Has Not Changed Much Over Time, Congressional Budget Office, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44176 (accessed May 14, 2013). |

| 2. | Monheit, Alan C., and Jessica Primoff Vistnes, Health Insurance Enrollment Decisions: Preferences for Coverage, Worker Sorting, and Insurance Take Up, Working Paper 12429, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass. (August, 2006). |

| 3. | Regression analysis was used to determine the extent to which variation in health insurance preferences across states reflect differences in individual characteristics of the uninsured. With health insurance preference as the dependent variables, regression models were estimated at the person-level, including individual characteristics (shown in Table 2), urban/rural location, and binary variables for each of the 29 states. The regression was used to compute adjusted estimates for each of the states, which account for differences in individual characteristics across the states. |

| 4. | This was determined by computing the coefficient of variation—a summary measure of the variation across states—for both adjusted and unadjusted percentages. A higher coefficient of variation indicates greater variation across states, while a coefficient of variation of 0 indicates no variation. As an example, if differences in characteristics of the uninsured accounted for all of the variation in health insurance preferences across states, then the coefficient of variation for the adjusted estimates would be close to zero, and the amount of variation explained by individual characteristics would be close to 100%. |

| 5. | Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: June 2013, http://kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-june-2013/. |

Back to Top

Data Source

This Research Brief is based on the 2008-2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Household Component (MEPS-HC), a nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population conducted annually by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The primary sample for this analysis includes about 18,000 persons aged 18 to 64 who were uninsured for the entire calendar year in which they participated in the study. Although MEPS is intended primarily for national estimates, 29 states have sufficient sample sizes for state-specific estimates. State-specific samples for the uninsured population were increased by combining 5 years of the MEPS (2006-2010). National estimates are weighted to be nationally representative of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population. State estimates are based on weights designed to be representative of each of the respective states.

Supplementary Tables

Funding Acknowledgement

This Research Brief was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. As the nation's largest philanthropy devoted exclusively to health and health care, RWJF works with a diverse group of organizations and individuals to identify solutions and achieve comprehensive, measurable and timely change.