Issue Brief No. 138

July 2012

Tracy Yee, Jon B. Christianson, Paul B. Ginsburg

Over the past decade, large employers increasingly have bypassed traditional health insurance for their workers, opting instead to assume the financial risk of enrollees’ medical care through self-insurance. Because self-insurance arrangements may offer advantages—such as lower costs, exemption from most state insurance regulation and greater flexibility in benefit design—they are especially attractive to large firms with enough employees to spread risk adequately to avoid the financial fallout from potentially catastrophic medical costs of some employees. Recently, with rising health care costs and changing market dynamics, more small firms—100 or fewer workers—are interested in self-insuring health benefits, according to a new qualitative study from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Self-insured firms typically use a third-party administrator (TPA) to process medical claims and provide access to provider networks. Firms also often purchase stop-loss insurance to cover medical costs exceeding a predefined amount. Increasingly competitive markets for TPA services and stop-loss insurance are making self-insurance attractive to more employers. The 2010 national health reform law imposes new requirements and taxes on health insurance that may spur more small firms to consider self-insurance. In turn, if more small firms opt to self-insure, certain health reform goals, such as strengthening consumer protections and making the small-group health insurance market more viable, may be undermined. Specifically, adverse selection—attracting sicker-than-average people—is a potential issue for the insurance exchanges created by reform.

![]() aced with rising health insurance premiums and the fallout from the economic downturn, many small employers are struggling to maintain health benefits for workers. At the same time, the markets for both third-party-administrative services and stop-loss insurance are becoming increasingly competitive as some carriers offer services to firms with as few as 10 workers. In turn, more small firms are considering self-insurance as an alternative to traditional health insurance products, according to interviews with health plans, stop-loss insurers and third-party administrators (see Data Source).

aced with rising health insurance premiums and the fallout from the economic downturn, many small employers are struggling to maintain health benefits for workers. At the same time, the markets for both third-party-administrative services and stop-loss insurance are becoming increasingly competitive as some carriers offer services to firms with as few as 10 workers. In turn, more small firms are considering self-insurance as an alternative to traditional health insurance products, according to interviews with health plans, stop-loss insurers and third-party administrators (see Data Source).

Self-insurance, or self-funding, is an arrangement where an employer— rather than an insurance carrier—assumes the financial risk for the cost of covered workers and dependents’ medical care. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, a federal law governing pensions and health plans, exempts self-insured employer health benefits from most state insurance regulations. In a self-insured plan, employees typically contribute a share of the premium—known as a premium-equivalent in self-insured plans—and pay a portion of their medical costs through deductibles, coinsurance and copayments, but their employers assume the risk of paying the remaining costs of covered services.

Self-insured employers contract with third-party administrators to establish and manage a provider network, pay claims and perform other services typically conducted by an insurer. Employers usually purchase stop-loss insurance to mitigate the risk of large medical costs incurred by individuals in a given year and/or aggregate expenses across enrollees who substantially exceed annual projected amounts. Stop-loss coverage kicks in depending on attachment points, or specific-dollar thresholds that an employer must reach in health expenditures before a stop-loss carrier takes over payment of all or a percentage of medical claims.

Self-insurance offers a number of advantages for employers, including lower premiums in return for taking on the risk of covering workers’ medical costs. Another advantage is greater flexibility in the health benefits they provide. For example, self-insured plans avoid state insurance regulation, including mandated benefits. As a result, self-insuring allows firms with employees in multiple states to offer a uniform benefit structure for all of their employees. Self-insured employers also have access to claims data, which is especially important to large employers seeking to understand health spending trends. Finally, self-insurance helps firms manage cash flow, since funds are not drawn until claims are processed. As one health plan respondent said, “[Employers] find that the fully insured environment is constraining. They don’t have the ability to manage the costs of health care, and they’re held hostage to premium increases that fully insured carriers issue, so people are looking to have more control over their own destiny.”

But, self-insured employers still face uncertainty about the costs of health benefits—although stop-loss insurance can mitigate these risks—and the uncertainty increases as firm size declines. Small firms are much more vulnerable to the costs of a catastrophic illness of one or two employees and typically need stop-loss coverage with much lower attachment points than large employers that can spread risk over a larger employee base. The greater financial risk and sometimes higher cost of stop-loss insurance offsets the attractiveness of self-insurance for smaller firms.

![]() verall, in 2011, about 60 percent of U.S. workers covered by employer-sponsored health insurance were in firms that self-insure, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).1 Over the last decade, the proportion of large employers opting to self-insure has grown significantly. According to KFF, 62 percent of workers in large firms offering coverage—5,000 or more employees—were in self-insured plans in 1999, increasing to 96 percent of workers in 2011. In firms with 1,000 to 4,999 workers, the proportion of workers in self-insured plans also grew from 62 percent in 1999 to 79 percent in 2011.

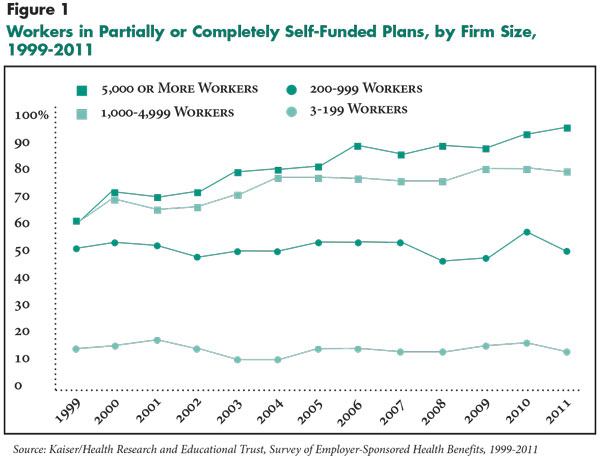

verall, in 2011, about 60 percent of U.S. workers covered by employer-sponsored health insurance were in firms that self-insure, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).1 Over the last decade, the proportion of large employers opting to self-insure has grown significantly. According to KFF, 62 percent of workers in large firms offering coverage—5,000 or more employees—were in self-insured plans in 1999, increasing to 96 percent of workers in 2011. In firms with 1,000 to 4,999 workers, the proportion of workers in self-insured plans also grew from 62 percent in 1999 to 79 percent in 2011.

A similar trend has not emerged among mid-sized and small firms—likely because of the greater financial risk they face if self-insured. For example, during the same period, the proportion in firms with 200 to 999 workers in self-insured plans remained steady at about 50 percent, and a much smaller proportion of workers in small firms—three to 199 employees—were in self-insured plans, with the proportion varying from 10 percent to 17 percent (see Figure 1).

![]() everal respondents reported that the markets for both third-party-administrative services and stop-loss insurance have become more competitive, which has spurred interest in self-insurance. Large insurers, which often offer TPA services and stop-loss products, promote their competitive advantages as a one-stop option for employers interested in self-insurance. Respondents indicated that there is an array of health insurers and general stop-loss carriers offering stop-loss products, leading to more competitive pricing. The affordability of stop-loss coverage is especially relevant to small employers, since stop-loss insurance prices are a larger factor in their costs to self-insure.

everal respondents reported that the markets for both third-party-administrative services and stop-loss insurance have become more competitive, which has spurred interest in self-insurance. Large insurers, which often offer TPA services and stop-loss products, promote their competitive advantages as a one-stop option for employers interested in self-insurance. Respondents indicated that there is an array of health insurers and general stop-loss carriers offering stop-loss products, leading to more competitive pricing. The affordability of stop-loss coverage is especially relevant to small employers, since stop-loss insurance prices are a larger factor in their costs to self-insure.

According to respondents, small employers also increasingly perceived that self-insurance may insulate them from health insurers’ strategic marketing and pricing decisions that are unrelated to an individual employer’s particular claims experience. Some employers believed that health plans raised premiums aggressively during recent renewal periods because insurers expect that, under health reform, state regulators will scrutinize premium increases more closely. Beginning in 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) required state review of premium rate increases for nongroup, small-group and fully insured large group plans. Self-insured employer plans are not subject to this review. As a result, more employers have reportedly considered self-insurance as a possible cost-saving strategy.

![]() hile the health reform law holds self-insured plans responsible for some of the same taxes and fees as fully insured plans, self-insured plans are exempt from exposure to the excise tax on insurance, community rating on premiums and mandates for essential health benefits.2 Beginning in 2014, PPACA requires modified community rating in the individual and small-group health insurance markets that will allow insurers to vary rates only based on age, geographic location, family size and smoking status. These rating rules will apply to products offered in the state insurance exchanges and to fully insured products purchased outside of the exchanges by employers with up to 100 employees. The maximum ratio of rates for older people compared to those for younger people will be 3:1, in contrast to a 5:1 or 6:1 ratio that insurance respondents indicated is typical of pricing in states that do not now restrict age rating. This change in rating method may draw firms with younger workforces toward self-insuring.

hile the health reform law holds self-insured plans responsible for some of the same taxes and fees as fully insured plans, self-insured plans are exempt from exposure to the excise tax on insurance, community rating on premiums and mandates for essential health benefits.2 Beginning in 2014, PPACA requires modified community rating in the individual and small-group health insurance markets that will allow insurers to vary rates only based on age, geographic location, family size and smoking status. These rating rules will apply to products offered in the state insurance exchanges and to fully insured products purchased outside of the exchanges by employers with up to 100 employees. The maximum ratio of rates for older people compared to those for younger people will be 3:1, in contrast to a 5:1 or 6:1 ratio that insurance respondents indicated is typical of pricing in states that do not now restrict age rating. This change in rating method may draw firms with younger workforces toward self-insuring.

In addition, nongroup and fully insured small-group plans will have to provide an essential health benefits package that covers a standardized set of benefits, as determined by federal and state requirements. Though PPACA specifies that the essential health benefits package should be equal in scope to those offered by a typical employer plan, small employers that want to potentially save money by offering less generous coverage may opt to self-insure.

Respondents also suggested that employers may see self-insurance as a way to manage uncertainty about the impact of greater regulation of the health insurance industry under PPACA. For example, by not being subject to review of medical-loss ratios that indicate how premium dollars are spent, self-insured employers may avoid exposure to the potential administrative burden and complexities involved with the process.

![]() he intersection of state and federal policies, some not yet fully formed, make the future costs and benefits of self-insurance, as well as its overall prevalence among small firms, highly uncertain. Rising premiums, coupled with new regulations on fully insured products and declining costs of stop-loss insurance, could lead to an increase in self-insurance among small employers, which could pose challenges for state and federal policy makers.

he intersection of state and federal policies, some not yet fully formed, make the future costs and benefits of self-insurance, as well as its overall prevalence among small firms, highly uncertain. Rising premiums, coupled with new regulations on fully insured products and declining costs of stop-loss insurance, could lead to an increase in self-insurance among small employers, which could pose challenges for state and federal policy makers.

The potential for adverse selection, or attracting a much sicker population than average, in health plans offered to small groups—whether in or outside state exchanges—has been cited as a primary concern by market observers. Small employers’ decisions about self-insurance may be influenced by the risk profile of their workforce, which could disrupt the small-group market risk pool. Also, if small employers that self-insure fail to purchase adequate stop-loss coverage, large unexpected medical claims could threaten the firms’ financial solvency and result in unpaid enrollee medical claims.

Some respondents suggested that growth in self-insurance among small employers could complicate some federal health reform goals, including making coverage affordable for older people. When the new rating requirements are in place, small employers with younger workforces could pay more than they currently do for a fully insured plan, whether purchased inside or outside the exchanges. This could make self-insurance more attractive to such firms but not for those with older workforces. A greater concentration of older workers in fully insured plans could lead to higher premiums and create a market dynamic that encourages still more employers to exit the state-regulated health insurance market in favor of self-insurance.

In a separate but related PPACA provision, beginning in 2017, states can decide whether larger firms—those with more than 100 employees—can purchase coverage in the exchanges. If states allow this, the potential for adverse selection could increase, since larger firms with older and/or sicker workers that now self-insure might find it advantageous to buy coverage in the exchange, while those with younger and/or healthier workforces would continue to self-insure. Although the law is silent on whether insurers need to charge the same price for coverage of larger firms inside or outside the exchange, such adverse selection would be a problem in either case.

PPACA recognized these issues and mandated a study “to determine the extent to which its insurance market reforms are likely to cause adverse selection in the large group market or to encourage small and midsize employers to self-insure.” The study, conducted by RAND Health, predicted a sizable increase in self-insurance only if stop-loss policies with low individual attachment points—for example, $20,000—become widely available after the law takes full effect in 2014.3 But, the market for stop-loss insurance already is moving toward lower attachment points. HSC study respondents indicated that policies with low attachment points are likely to be widely available, noting that policies with stop-loss attachment points as low as $10,000 are marketed today.

Another policy issue related to extremely low attachment points for stop-loss coverage raises questions about how much risk self-insured firms are bearing and whether self-insurance is merely a way to avoid state insurance regulation. Such concerns have precedent. In the past, fraud and insolvencies involving Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangements, or MEWAs, where small firms banded together to self-insure workers, have left enrollees unprotected and liable for their medical costs.4

Because of these concerns, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) has charged a working group to look into updating recommendations to states about regulating stop-loss insurance. The NAIC created a model law in 1995 that prohibits specific individual attachment points lower than $20,000 and aggregate attachment points lower than 120 percent of expected claim costs for groups with 50 or fewer members. NAIC has been discussing revisions to this model law that may include higher attachment points, which might preclude many small firms from self-insuring.

Policy options for revising regulation of stop-loss coverage for small groups have been offered for states to consider and may be a necessary step toward ensuring stability of the small-group market and state exchanges.5 The California Department of Insurance is pursuing legislation to ban stop-loss attachment points below $95,000 per employee, which would make it more difficult for most small employers to obtain adequate stop-loss coverage.6 Depending on how the California legislation proceeds, other states may follow suit with similar legislation designed to curtail small employers from opting for self-insured health plans with low attachment points.

This Issue Brief draws on interviews with representatives of a variety of organizations involved in self-insurance. Initial information was gathered through HSC’s 2010 Community Tracking Study (CTS) site visits, which included 174 interviews with health plans, benefits consulting firms and other private-sector market experts on a variety of topics. In addition, HSC researchers conducted literature reviews and additional in-depth interviews specifically on self-insurance with more representatives from health plans, reinsurers and third-party administrators. The additional interviews were conducted between April and June 2011.

The 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits and resulting research and publications were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform.