Issue Brief No. 137

October 2011

Jon B. Christianson, Ha T. Tu, Divya R. Samuel

Rising costs and the lingering fallout from the great recession are altering the calculus of employer approaches to offering health benefits, according to findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC) 2010 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities. Employers responded to the economic downturn by continuing to shift health care costs to employees, with the trend more pronounced in small, mid-sized and low-wage firms. At the same time, employers and health plans are dissatisfied and frustrated with their inability to influence medical cost trends by controlling utilization or negotiating more-favorable provider contracts. In an alternative attempt to control costs, employers increasingly are turning to wellness programs, although the payoff remains unclear. Employer uncertainty about how national reform will affect their health benefits programs suggests they are likely to continue their current course in the near term. Looking toward 2014 when many reform provisions take effect, employer responses likely will vary across communities, reflecting differences in state approaches to reform implementation, such as insurance exchange design, and local labor market conditions.

![]() iven the unexpected depth of the economic downturn, employers of all types are reconsidering health benefit strategies, according to findings from HSC’s 2010 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities (see Data Source).

iven the unexpected depth of the economic downturn, employers of all types are reconsidering health benefit strategies, according to findings from HSC’s 2010 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities (see Data Source).

While it is convenient to refer to employer-sponsored health insurance as a single concept, the health-benefit needs of employers differ dramatically, with the differences more pronounced in the wake of the 2007-09 recession. The mix of employers—small vs. large, low wage vs. high wage, public vs. private, and national vs. local—differs across communities, contributing to variation in the popularity of benefit designs, such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and high-deductible plans. Increasingly, differences across communities in employer-sponsored health insurance reflect differences in the structure of local health care delivery systems as well.

Existing cross-community variation in employer-sponsored insurance suggests that the impact of national health reform also will vary substantially across communities, regardless of whether implementation occurs primarily through federal actions or is delegated in large part to the states.

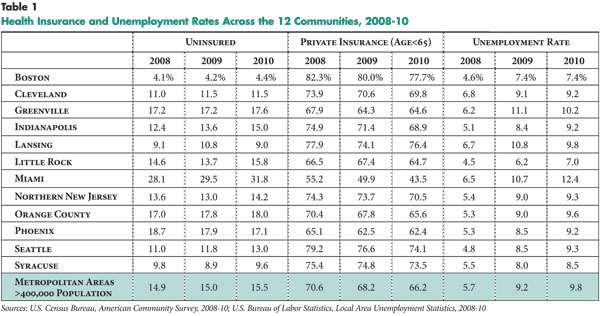

![]() he severity of the recession varied widely across the 12 communities, with 2010 unemployment rates ranging from 7 percent in Little Rock to 12.4 percent in Miami (see Table 1). In large part, the variation reflects labor market differences, with communities dependent on relatively stable sectors, such as government, health and education, generally losing far fewer jobs than communities more reliant on the construction and finance sectors. While job losses led to declines in employer-sponsored insurance, overall uninsurance rates increased modestly. In many cases, people likely gained private coverage through a spouse or public coverage through Medicaid or other sources.

he severity of the recession varied widely across the 12 communities, with 2010 unemployment rates ranging from 7 percent in Little Rock to 12.4 percent in Miami (see Table 1). In large part, the variation reflects labor market differences, with communities dependent on relatively stable sectors, such as government, health and education, generally losing far fewer jobs than communities more reliant on the construction and finance sectors. While job losses led to declines in employer-sponsored insurance, overall uninsurance rates increased modestly. In many cases, people likely gained private coverage through a spouse or public coverage through Medicaid or other sources.

The recession deepened already-intense cost pressures on employers from longer-term utilization and provider payment rate trends that insurers have been unable or unwilling to contain.1 From 2001 to 2010, the total cost of family health insurance premiums increased 113 percent on average, far outpacing the growth in wages (34%).2 As a result, employers, particularly small employers, continued to increase the share of health care costs borne by workers. While some low-wage, small firms dropped coverage altogether, others took steps to reduce costs, including reducing or eliminating dependent coverage and increasing both the share of employee premium contributions and patient cost sharing at the point of service.

Increased patient cost sharing. Cost pressures on employers led to increasing adoption of consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs)—high-deductible plans typically paired with either a tax-advantaged health savings account or a health reimbursement arrangement. Across the 12 communities, CDHP enrollment grew from a negligible base to become a significant portion of small-group enrollment and a modest portion of overall commercial enrollment. These trends are confirmed by a recent survey showing that, among firms with fewer than 200 workers, 50 percent of covered workers are enrolled in high-deductible health plans; across all firms, 31 percent are enrolled in such plans.3

Experts observed that many employers adopting CDHPs are focused primarily or exclusively on premium savings rather than promoting consumer engagement. Employers that could afford to do so often contributed to tax-advantaged savings accounts or other wraparound arrangements to help shield employees from high out-of-pocket costs in CDHPs. However, these practices are far less common among small employers, where the decision often is to offer high-deductible coverage without an account contribution or no coverage.

While CDHPs gained traction in some markets, the broader consumerism movement—consumers having information on prices, quality and treatment alternatives and taking more responsibility for their health and care decisions—lagged. Although price and quality transparency initiatives increased in recent years across the 12 communities studied, programs providing consumers with actionable, provider-specific information remained rare. And, even when useful consumer-support tools were introduced in a handful of markets—such as well-regarded quality transparency initiatives in Orange County and Boston—consumer awareness and use of these tools reportedly remained limited.

Among large employers adopting CDHPs, most continued to offer traditional products as well but encouraged employees to choose CDHPs by offering substantial savings account contributions and/or lowering employee premium contributions. Once CDHP enrollment reaches a certain level after a few years, for example, 25 percent, an employer might switch the CDHP to the default option and require employees to pay more for other coverage. Indianapolis stood out as an exception to this cautious, gradual approach, with pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly joining early CDHP-adopter Marsh Supermarkets in implementing total CDHP replacement. Also, Indiana state government—while barred by state law from adopting total replacement—differentiated itself from public employers in other communities by strongly incentivizing CDHPs, with 85 percent of employees opting for CDHPs.

Employers also continued to increase patient cost sharing in traditional preferred provider organization (PPO) and HMO products. By 2007, some market observers had suggested that patient cost sharing had reached a saturation point and that employers would have to find alternatives to moderate premium increases. However, the recession changed those views, and employers continued to pass more costs along to employees. One result is that distinctions between CDHPs and conventional PPOs have blurred, as average deductibles for the latter reached $1,000 in some markets.

In markets with a historically strong managed care presence, employers continued to transition from HMOs with first-dollar coverage to HMOs with deductibles. In Orange County, for example, about 80 percent of Kaiser Permanente employer accounts now offer an HMO with a deductible, either as the sole benefit offering or requiring the employee to pay the premium differential for first-dollar coverage. This move from first-dollar coverage helped HMOs keep premium increases in check and maintain market share for the most part in areas where they have been strong—such as Boston and Miami, as well as Orange County.

Limited-network products. Two health plan approaches to limiting provider networks—narrow networks and tiered networks—first attracted attention a decade ago, when large employers sought these options as part of a value-based purchasing strategy. Narrow-network products exclude nonpreferred providers from the network altogether, while tiered-network products place these providers in tiers requiring higher cost sharing at the point of service.

To date, however, these products have not gained much ground in the large-group market, in part because employers have found the premium differential too small—typically 10 percent for narrow networks and 5 percent for tiered networks—to justify sacrificing broad provider choice. However, in some communities, limited-network products made headway in the acutely cost-conscious, small-group market.

Most tiered- and narrow-network products focus on restricting physician networks over hospital networks, in part because hospital systems with negotiating leverage typically can avoid either being placed in less-preferred tiers or being excluded from narrow networks. Plans also face pushback—albeit to a lesser extent—from physicians, whose lawsuits in some markets have challenged the validity of plan designations of high-performing physicians.

Although products limiting physician networks are more common, tiered-hospital designs introduced by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts have caught on in Boston. First introduced or revamped in 2010, these products impose large out-of-pocket penalties for using lower-tier (higher-cost) hospitals, including the renowned flagships of Partners HealthCare and Children’s Hospital Boston. About one-third of individual and small-group accounts renewing in early 2011 switched to one of these tiered-hospital products—by far the greatest penetration for any limited-network product across the 12 communities. The move toward these products largely reflects the impact of high and fast-growing hospital payment rates on already high insurance premiums in Boston.

According to market observers, what enabled Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts to implement tiered-hospital products was the intense scrutiny by state authorities and others of hospital rates and behavior, making it politically difficult for dominant providers to exercise their leverage fully to prevent placement in less-preferred tiers. And, since mid-2010, a state law has banned certain provider contracting practices, including making network participation contingent on being in a preferred tier.

In addition to these mainstream limited-network products, which are targeted at the entire small-group market, plans in a few communities also offer narrow-network products aimed at particular market niches. In Miami, for example, health plans target narrow-network HMO designs at the sizable population of Central and South American immigrants, who reportedly are more willing than many consumers to tolerate restrictions on provider choice in exchange for predictable out-of-pocket costs.

Going forward, tiered networks may gain wider acceptance than narrow networks, given the greater choice and flexibility they offer at the point of service. Their design is similar to employers’ pharmacy benefits programs, where three-tiered, cost-sharing designs are the norm, but closed formularies failed to flourish.

Limited-benefit products. As small businesses struggled with high and rising premiums during the recession, health plans in most markets rolled out limited-benefit, lower-premium products, typically marketed as “value plans” in the small-group market. In Greenville, Indianapolis and Phoenix, among other markets, plan products feature a fixed number of physician office visits for a fixed copayment amount; additional office visits and other services are subject to a deductible and a high rate of coinsurance. Some limited-benefit designs target pharmacy coverage, either placing a cap on total prescription drug benefits—for example, $500—or limiting drug coverage to generics only. While health plans continued to introduce variations of limited-benefit products to meet the demands of small or low-wage employers, they recognized that the products are unlikely to qualify for subsidies or satisfy mandates under health reform.

![]() n response to employers’ ongoing reluctance to antagonize employees, health plans in recent years refrained from stringent across-the-board utilization management, such as prior authorization and retrospective review of services. In some cases, plans also cited lack of evidence of return on investment and a desire not to provoke providers.

n response to employers’ ongoing reluctance to antagonize employees, health plans in recent years refrained from stringent across-the-board utilization management, such as prior authorization and retrospective review of services. In some cases, plans also cited lack of evidence of return on investment and a desire not to provoke providers.

Instead, plans focused utilization management on select high-cost and/or preference-sensitive services with substantial variation in provider-practice patterns—services such as imaging and treatment of low-back pain. For example, many plans increased use of prior authorization for high-cost imaging services, such as magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear cardiac imaging. A few plans reported using strategies to engage and educate providers or patients to help steer them, for example, to lower-cost imaging centers. The latter strategy is used in Indianapolis, where CDHP enrollment is relatively high and enrollees have more incentives to be cost-conscious consumers.

Across markets, utilization management varied in stringency and acceptance by providers. Some programs achieved notable success—for example, Excellus BlueCross BlueShield in Syracuse reduced growth in high-cost imaging from about 18 percent a year to zero through physician advisory groups and prior-authorization requirements. However, plans in several other markets noted barriers to effective utilization management, including provider pushback or circumvention, for example, through manipulation of billing codes.

Health plans reported increased use of predictive-modeling technologies that combine claims and other patient data to identify potentially high-cost enrollees for increased utilization- and care-management activities. While health plans in many of the 12 markets reported improvements in data systems, the extent to which this has enhanced patient care remains unclear.

The costs associated with specialty drugs—typically expensive biologic medications that require close monitoring and special handling—are an increasing concern for health plans and self-insured employers. Although the cost trend for conventional prescription drugs has slowed, specialty drug spending continues to grow at double-digit rates. Generic substitutes, which have been critical in moderating conventional drug trends, are largely unavailable for specialty drugs.

Health plans across the 12 communities own or contract with a limited number of specialty pharmacy vendors to negotiate unit prices and to manage distribution of specialty drugs. Beyond this basic strategy, benefit-design and utilization-management approaches vary widely. While prior authorization is required by nearly all plans and employers for specialty drugs covered through a pharmacy benefit, increased patient cost sharing through imposition of a fourth tier is more limited and controversial. Plans and employers all struggle to balance the inherent trade-offs of specialty drugs, which typically cost thousands of dollars per prescription but can be lifesaving and critical in managing complex diseases. The challenge of managing specialty drug spending is likely to grow as the number of drugs and patients who may benefit are expected to increase substantially. Plans and employers saw no obvious solutions—only more difficult trade-offs.

![]() he incorporation of health promotion and wellness components into employee benefits programs is growing, spreading from large, self-insured employers to even small groups. Nearly all commercial health insurance products include some basic wellness features built into the premium—a health risk assessment at a minimum and often additional Web-based wellness tools—with supplemental programs available for additional fees. One broker characterized these basic online features as “no-cost, no-payoff” features.

he incorporation of health promotion and wellness components into employee benefits programs is growing, spreading from large, self-insured employers to even small groups. Nearly all commercial health insurance products include some basic wellness features built into the premium—a health risk assessment at a minimum and often additional Web-based wellness tools—with supplemental programs available for additional fees. One broker characterized these basic online features as “no-cost, no-payoff” features.

Health plans have launched numerous products with more comprehensive wellness programs—including incentives for employee participation or achievement of health outcomes—in the fully insured small and mid-sized group markets. These products, however, have limited take up, because expanded wellness activities increase costs to employers immediately, but any savings through improved population health are uncertain. Cost pressures from the recession made small employers especially wary of paying additional premiums upfront for the promise of payoffs down the road.

Larger, self-insured employers—many of which adopted wellness strategies years ago, independent of health plans—are by far the most likely to pursue comprehensive wellness programs. Comprehensive programs include such features as biometric screenings and personalized health coaching that sometimes are coordinated with primary care and disease management programs. Large employers also are more likely to provide employee incentives—generally considered essential by health plans and benefits consultants—for completing a health risk assessment and participating in wellness activities.

Although small gifts or cash payments remain the most common incentives, many large employers have moved to stronger incentives, such as reductions in patient cost sharing or premiums. A few large employers are experimenting with penalties rather than rewards and basing incentives on achievement of health-outcome targets rather than simple participation in activities. Given larger employers’ continuing reluctance to face employee resistance to tighter utilization controls or limited-provider networks, comprehensive wellness programs are regarded as one of the few remaining tools to manage care and control costs.

![]() ealth care costs continue to grow at a faster rate than wages. With the recession as backdrop, employers sought to moderate their bottom-line impact by continuing to increase the portion of health care costs borne by employees. In the past, employers relied on health plans to moderate cost increases through price negotiations with providers. Now, with the exception of dominant Blues plans in a few communities, most health plans believe that—in geographic areas with substantial provider consolidation or other factors that contribute to provider market power—they have little negotiating leverage to hold down provider rate increases for services other than primary care. Larger employers, reflecting employee wishes, have maintained requirements that virtually all providers be included in plan networks, limiting demand for narrow- or tiered-network options. The inclusion of wellness programs in health benefit plans is a strategy that continues to garner employer support, but whether wellness programs can generate and sustain savings over time remains uncertain.

ealth care costs continue to grow at a faster rate than wages. With the recession as backdrop, employers sought to moderate their bottom-line impact by continuing to increase the portion of health care costs borne by employees. In the past, employers relied on health plans to moderate cost increases through price negotiations with providers. Now, with the exception of dominant Blues plans in a few communities, most health plans believe that—in geographic areas with substantial provider consolidation or other factors that contribute to provider market power—they have little negotiating leverage to hold down provider rate increases for services other than primary care. Larger employers, reflecting employee wishes, have maintained requirements that virtually all providers be included in plan networks, limiting demand for narrow- or tiered-network options. The inclusion of wellness programs in health benefit plans is a strategy that continues to garner employer support, but whether wellness programs can generate and sustain savings over time remains uncertain.

![]() arge, private-sector employers in virtually all 12 communities are likely to continue shifting costs to employees by adopting benefit designs that accommodate greater cost sharing. As part of this strategy, consumer-driven health plans are likely to become the only health benefit offered in more instances.

arge, private-sector employers in virtually all 12 communities are likely to continue shifting costs to employees by adopting benefit designs that accommodate greater cost sharing. As part of this strategy, consumer-driven health plans are likely to become the only health benefit offered in more instances.

In the public sector, unionized workers’ historically rich benefits have been largely shielded from significant reductions to date. However, with public-employee benefits coming under greater scrutiny as state and local budget woes worsen, cost sharing for public employees is already increasing in some markets and is likely to accelerate. Health care reform’s so-called “Cadillac plan” excise tax on high-cost health benefits starting in 2018 seems likely to reinforce the trend toward greater patient cost sharing among large employers.

More mid-sized firms, especially those with relatively healthy workforces, are likely to pursue self-insurance in an attempt to reduce health benefit costs and avoid minimum essential benefit requirements under health reform. A shift to self-insurance would continue longstanding trends, with the proportion of covered workers in partially or completely self-funded plans increasing from 44 percent in 1999 to 60 percent in 2011.4

Clearly, any assessment of the future of employer-sponsored health insurance is complicated by uncertainty about how employers will respond to provisions in the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Given the uncertainty, employers are likely to be relatively cautious in the near term, continuing on their present course while assessing longer-term options as the rules governing reform become clearer. A complicating factor in assessing possible employer responses to health reform is that implementation of various reform provisions is likely to vary across states. For instance, health plan rate increases likely will be subject to more aggressive review by some states than others. And, the way in which insurance exchanges are structured and implemented will vary across states as well.

While there is disagreement about how the number of employers offering health insurance will change—estimates range from a 9-percent increase to a 22-percent reduction5—employer opt-out decisions are likely to be influenced heavily by labor market conditions that vary across geographic areas and industries.

| 1. | Felland, Laurie E., Joy M. Grossman and Ha T. Tu, Key Findings from HSC’s 2010 Site Visits: Health Care Markets Weather Economic Downturn, Brace for Health Reform, Issue Brief No. 135, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (May 2011). |

| 2. | Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust (HRET), Employer Health Benefits 2011 Annual Survey, Washington, D.C. (September 2011). |

| 3. | Ibid. The Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits defines “high-deductible plans” as those with single-coverage deductibles of at least $1,000. |

| 4. | Ibid. |

| 5. | Avalere Health, The Affordable Care Act’s Impact on Employer Sponsored Insurance: A Look at the Microsimulation Models and Other Analyses, Washington, D.C. (June 2011). |

Every two years, HSC conducts site visits in 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities as part of the Community Tracking Study to interview health care leaders about the local health care market and how it has changed. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. Almost 550 interviews were conducted between March and October 2010 in the 12 communities. This Issue Brief is based primarily on responses from representatives from at least two of the largest commercial health plans—including medical directors, marketing executives, and network executives—as well as benefit consultants, brokers and representatives of at least two large employers in each community.

The 2010 Community Tracking Study site visits and resulting research and publications were funded jointly by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Reform.