Little Rock Health Care Safety Net Stretched by Economic Downturn

Community Report No. 5

January 2011

Jon B. Christianson, Emily Carrier, Marisa K. Dowling, Ian Hill, Ralph C. Mayrell, Tracy Yee

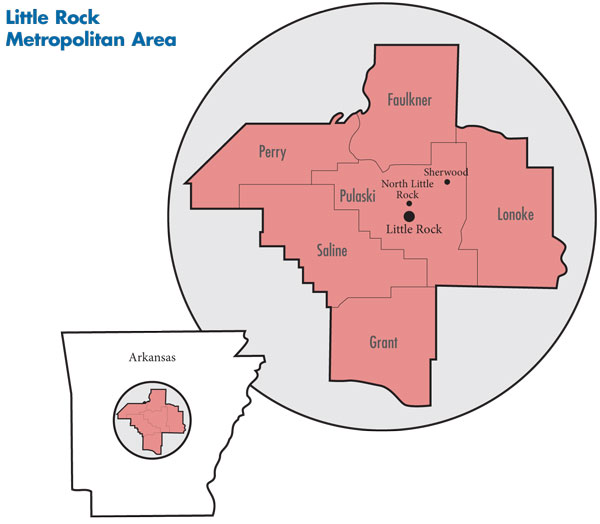

In May 2010, a team of researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), visited the Little Rock metropolitan area to study how health care is organized, financed and delivered in that community. Researchers interviewed more than 40 health care leaders, including representatives of major hospital systems, physician groups, insurers, employers, benefits consultants, community health centers, state and local health agencies, and others. The Little Rock metropolitan area encompasses Faulkner, Grant, Lonoke, Perry, Pulaski and Saline counties.

Although a large proportion of Little Rock’s population has low incomes, the health care safety net has limited capabilities, especially for adults. The economic downturn has been milder in Little Rock than elsewhere, but increased unemployment and an almost 15 percent uninsurance rate have strained the area’s fragmented safety net. The community has a single federally qualified health center (FQHC), a handful of free clinics and a relatively small number of primary care physicians. Children fare better than adults, however, as ARKidsFirst, Arkansas’ Child Health Insurance Program for low-income children, has less-stringent-eligibility requirements relative to the Medicaid program for adults.

Against this backdrop of limited access to care for low-income and uninsured adults, the Little Rock health care market, nonetheless, has far more hospital beds and specialty physicians per capita than other large metropolitan areas, reflecting in part the area’s role as a referral center for the rest of the state. Hospitals continue to add capacity and high-tech equipment to compete for well-insured patients in more affluent suburban areas and maintain their status as statewide referral centers for specialty care.

Key developments include:

- The increasing number of uninsured Little Rock residents, a consequence of the economic downturn, is placing a greater burden on Little Rock’s already-strained safety net providers.

- Little Rock hospital systems have moved to shore up their finances, update and expand their facilities, align more closely with physicians, and protect their positions as statewide referral centers for specialty services.

- While some skirmishing between health plans and providers continues over the state’s controversial any-willing-provider (AWP) law, the measure, despite predictions to the contrary, appears to have changed market dynamics little, with market share of both hospitals and health plans remaining fairly constant.

- Low Incomes and High Uninsurance

- Adults Lack Access to Primary Care

- Commitment Remains to Children

- Sparse Safety Net for Uninsured

- Hospitals Shore Up Finances, Compete for Well Insured

- Hospital-Physician Relations

- Pressure to Keep Premium Increases Down

- Anticipating Health Reform

- Issues to Track

- Background Data

Low Incomes and High Uninsurance

![]() ocated in Central Arkansas, Little Rock is a sparsely populated metropolitan area, with 685,000 residents across six counties in 2009 (see map below). However, from 2004 to 2009, the area’s population grew faster than the average for large metropolitan areas (7.6% vs. 5.5%). Incomes of Little Rock residents are relatively low, with only 45.3 percent living in households with incomes above $50,000 in 2008, compared with 56.1 percent in large metropolitan areas. Little Rock’s racial and ethnic composition differs markedly from other large metropolitan areas, with higher proportions in 2008 of both whites (71%) and blacks (22.1%) and fewer Latino (3.6%) and Asian (1.3%) residents.

ocated in Central Arkansas, Little Rock is a sparsely populated metropolitan area, with 685,000 residents across six counties in 2009 (see map below). However, from 2004 to 2009, the area’s population grew faster than the average for large metropolitan areas (7.6% vs. 5.5%). Incomes of Little Rock residents are relatively low, with only 45.3 percent living in households with incomes above $50,000 in 2008, compared with 56.1 percent in large metropolitan areas. Little Rock’s racial and ethnic composition differs markedly from other large metropolitan areas, with higher proportions in 2008 of both whites (71%) and blacks (22.1%) and fewer Latino (3.6%) and Asian (1.3%) residents.

The recession had a somewhat delayed and less severe impact in Little Rock than elsewhere. Little Rock’s unemployment rate had been lower than the average for large metropolitan areas (4.5% vs. 5.7% in 2008) and has increased at a much slower rate, reaching 6.8 percent in May 2010, compared with 9.5 percent in large metropolitan areas. The less severe impact of the recession on unemployment in Little Rock can be attributed in part to the roles that the relatively stable public—Little Rock is the state capital—and health care sectors play in the local economy. Nevertheless, Little Rock’s uninsurance rate is approximately the same as the average for large metropolitan areas (14.6% vs. 14.9% in 2008).

Little Rock has three large hospital systems, Baptist Health, St. Vincent Health System and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS). Baptist Health leads in size and market share, with two hospitals in the metropolitan area—the system’s flagship hospital, Baptist Health Medical Center-Little Rock, and a smaller hospital in the more affluent suburb of North Little Rock—and community hospitals outside the metropolitan area in Heber Springs, Arkadelphia and Stuttgart.

St. Vincent Health System—part of Catholic Health Initiatives, a large system with 73 hospitals in 19 states—operates St. Vincent Infirmary Medical Center in Little Rock and St. Vincent Medical Center North in Sherwood, north of Little Rock in Pulaski County, along with a community hospital outside the study area in Conway County, northwest of Little Rock.

UAMS is a state-funded academic health center with the state’s only medical school, a large teaching hospital—UAMS Medical Center—and a 700-physician multispecialty faculty group practice.

While the three systems differ in size and structure, all are statewide referral centers for various specialty services. UAMS and St. Vincent, which operates three free community-based clinics, also provide significant charity care, but UAMS is actively working to shift its image from a public hospital serving the poor to an elite academic health center that also serves as a safety net provider. Arkansas Children’s Hospital, in addition to providing specialized pediatric services, is the primary safety net provider of inpatient and outpatient services for children and recently expanded from 275 to 316 beds with plans to expand capacity to 375 beds. The UAMS College of Medicine faculty also provides patient care at the children’s hospital.

Other hospitals in the market include the Arkansas Heart Hospital, which opened in 1998, and the Arkansas Surgical Hospital, formed in 2005 by orthopedists, neurosurgeons and plastic surgeons.

Aside from physicians directly employed by hospital systems, Little Rock physicians typically work in small, independent practices, with relatively few large, multispecialty groups. Little Rock Diagnostic Clinic, with more than 40 physicians in six specialties, is an important exception.

The private insurance market is heavily concentrated. Arkansas BlueCross BlueShield (ABCBS) is the dominant insurer, operating the largest health maintenance organization (HMO) and preferred provider organization (PPO) in the Little Rock market and throughout the state. ABCBS covers about two-thirds of privately insured Little Rock-area residents, while two other plans—locally based QualChoice and national carrier UnitedHealth Group—divide the remaining third.

Little Rock health plans and hospital systems are linked through ownership arrangements that mirrored alliances when ABCBS and Baptist maintained an exclusive contracting arrangement that excluded St. Vincent and UAMS from the Blue’s provider network. While the AWP law has dissolved the exclusive ABCBS-Baptist agreement, Baptist remains a co-owner of ABCBS’ HMO Partners, and UAMS and St. Vincent have ownership stakes in QualChoice.

Adults Lack Access to Primary Care

![]() ccess to primary care reportedly is challenging for Little Rock residents—particularly for low-income adults covered by Medicaid and uninsured adults. Little Rock has 77 primary care physicians per 100,000 residents, while large metropolitan areas average 83 per 100,000 residents. One respondent indicated that most primary care physicians in Little Rock had “all the business they could handle.”

ccess to primary care reportedly is challenging for Little Rock residents—particularly for low-income adults covered by Medicaid and uninsured adults. Little Rock has 77 primary care physicians per 100,000 residents, while large metropolitan areas average 83 per 100,000 residents. One respondent indicated that most primary care physicians in Little Rock had “all the business they could handle.”

Several respondents said access to primary care for adult Medicaid patients was worsening as many primary care physicians do not accept Medicaid because of low reimbursement rates and full practices. In some cases, primary care physicians also are limiting the number of Medicare patients they see—reportedly commercial insurance payment rates to physicians exceed Medicare rates substantially. According to some respondents, addressing the primary care access problem is complicated by the state medical society’s objections to legislation expanding the scope of practice for mid-level practitioners, such as advanced nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Other than for pregnant women and aged and disabled people, Arkansas has among the most-stringent Medicaid eligibility requirements for adults in the nation, providing coverage to parents with a dependent child with incomes at about 17 percent of the federal poverty level, or $3,750 for a family of four in 2010. Consequently, only 12 percent of the state’s adult population is enrolled in Medicaid.

A limited benefit plan established by the state in 2006 to subsidize care for the working poor (ARHealthNetwork) has improved access to primary and specialty care for program participants, but its overall impact has been limited. The program enrolls only 10,000 people statewide, possibly because of limited benefits and the initial exclusion of sole proprietors.

Because of Arkansas’ relatively low average income, the federal government pays about 73 percent of the state’s Medicaid expenses. Even so, facing a state budget shortfall in 2010, Arkansas Medicaid expected to cut expenditures by $400 million, or 11 percent of the Medicaid budget. The extension of enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds, initially included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, forestalled those cuts. According to one respondent, “Without the stimulus funds, I don’t know where we would be. We would’ve exhausted our Medicaid trust fund.” Efforts by state officials are now underway to restrain what is perceived as “unsustainable” growth in Medicaid spending. State officials are bracing for expected budget shortfalls that could reach almost $400 million by July 2013 given the state’s current revenue forecast.

The expansion of Medicaid eligibility under federal health reform is expected to make insurance available to many more people in Arkansas. Given the low median income in Arkansas, one respondent observed that many residents are likely to have their health care subsidized through one of the various mechanisms established by health care reform. One respondent estimated that the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to people with incomes up to 138 percent of poverty under health reform would add 200,000 to 250,000 people to Arkansas Medicaid rolls. An increase in the Medicaid population of this magnitude is expected to be administratively challenging for the program and place significant financial pressure on the state budget. Although health reform provides a 100 percent federal match for new Medicaid enrollees for several years, one respondent estimated that the state’s Medicaid budget could increase $100 million to $200 million annually when that federal match declines by 10 percentage points for 2019 and beyond.

Commitment Remains to Children

![]() n contrast to limited public coverage for adults, the state has had a long-term commitment to improving access to primary care and other services for children. Low-income children appear to have better access to primary care than adult Medicaid patients and the uninsured, primarily because of ARKidsFirst, a state program created through the federal Medicaid waiver process in 1998 and now part of the state Children’s Health Insurance Program.

n contrast to limited public coverage for adults, the state has had a long-term commitment to improving access to primary care and other services for children. Low-income children appear to have better access to primary care than adult Medicaid patients and the uninsured, primarily because of ARKidsFirst, a state program created through the federal Medicaid waiver process in 1998 and now part of the state Children’s Health Insurance Program.

ARKids extends coverage to children in families with incomes up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $44,100 for a family of four in 2010, providing children with benefits that essentially mirror Medicaid. The ARKids program enjoys considerable political support. In addition to providing insurance coverage to 63 percent of all Arkansas children in 2009, ARKids reimbursement rates for primary care reportedly are higher than Medicaid rates, facilitating access to primary care for children. Still, some private physicians limit the number of ARKids patients they accept in their practices as well, according to respondents.

Sparse Safety Net for Uninsured

![]() n addition to the relatively limited supply of primary care physicians, Little Rock’s safety net is sparse, lacking adequate capacity to meet low-income people’s needs for outpatient care of all types. While UAMS and Arkansas Children’s Hospital provide outpatient services in addition to their core inpatient services, there are few other primary care providers in the community who are significant providers of care to the uninsured.

n addition to the relatively limited supply of primary care physicians, Little Rock’s safety net is sparse, lacking adequate capacity to meet low-income people’s needs for outpatient care of all types. While UAMS and Arkansas Children’s Hospital provide outpatient services in addition to their core inpatient services, there are few other primary care providers in the community who are significant providers of care to the uninsured.

Little Rock has a single federally qualified health center, Jefferson Comprehensive Care System, or JCCS, with two clinic sites in the metropolitan area—ne comprehensive clinic and one homeless health care site. JCCS does not have a direct relationship with any of the hospital systems and recently closed a clinic in the Little Rock area. The FQHC had planned to establish a new clinic in North Little Rock but was unsuccessful in acquiring ARRA funding for new construction. However, JCCS did receive ARRA stimulus funding to update equipment and extend service hours at existing facilities. The FQHC also received state assistance from tobacco tax revenues, helping to stabilize its finances.

There are about 10 free clinics—typically church affiliated—in Little Rock that vary in size and scope. While the clinics offer a fairly wide range of services, including acute medical treatment, pharmacy services, and, in some cases, dental care, the clinics are not considered comprehensive primary care sites because they operate during limited hours and only on select days of the week. They are dependent on volunteer staff, although some have taken advantage of a recent infusion of state funding to purchase a limited amount of clinician time. Free clinics define their mission as providing care to poor adults who do not have insurance coverage of any type, but clinic administrators do not believe that they are filling the need for outpatient care adequately for this group of patients. To cope with demand, the clinics turn away children and adults with coverage, including Medicaid. Consistent with their missions, the free clinics make no attempt to collect payment for services or enroll patients in Medicaid.

Accessing specialty care reportedly is also difficult for low-income people, as they often rely on a limited number of individual specialists in the community for care, and the specialists who do serve low-income people reportedly have become overwhelmed.

Indeed, safety net providers reported an increased demand for their services in the past two years, which most attributed to the recession. Market observers reported that when people lose their insurance, primary care physicians are less likely to see them, leading them to seek care in hospital emergency departments (EDs) instead. JCCS also reported increased demand but a decline in the total volume of care provided because of the closure of a clinic site. Free clinics are treating more patients, but their capacity is strained, as one free clinic director said, “We turn away as many as we see.”

Hospitals Shore Up Finances, Compete for Well-Insured

![]() n recent years, the three large Little Rock hospital systems have focused on shoring up their financial positions, an effort complicated by the economic downturn. At the same time, the hospital systems continue to compete aggressively for well-insured patients while maintaining their status as statewide referral centers.

n recent years, the three large Little Rock hospital systems have focused on shoring up their financial positions, an effort complicated by the economic downturn. At the same time, the hospital systems continue to compete aggressively for well-insured patients while maintaining their status as statewide referral centers.

Although overall volume has changed little—with the exception of a recent rise in inpatient volume at UAMS—the systems have experienced drops in elective procedures. Hospital leaders cited rising numbers of uninsured and underinsured patients, combined with unit cost growth that has exceeded public and private payer rate increases, as contributing to a challenging financial environment.

The hospital systems have adopted a number of strategies to improve their financial positions with a particular focus on cutting costs by eliminating staff positions or reducing employees’ hours. St. Vincent is attempting to position itself as a lower-cost alternative to Baptist, while emphasizing specialty-service lines where it has particular strengths and seeking more favorable reimbursement from health plans. Baptist Health, St. Vincent and UAMS all struggled finanically during the recession but have regained their financial footing, although UAMS has shouldered considerable debt after building a new hospital and financing other expansions. However, Arkansas Children’s Hospital recently announced a revenue shortfall as a result of lower-than-expected inpatient stays.

Even in the face of short-term financial challenges, Little Rock’s hospital systems have invested in infrastructure to extend their presence beyond their flagship institutions into suburban, relatively well-insured areas of Little Rock. This strategy is also a response to investments in advanced diagnostic and surgical equipment by regional medical centers outside of the Little Rock area. The Little Rock systems hope to hold on to patients who have used their flagship facilities for specialty services in the past. In one example of this strategy, St. Vincent has embarked on the development of a 37-acre parcel in a well-insured, west Little Rock area as a “medical village” to include physician offices and outpatient treatment facilities.

There has been a considerable amount of competition among Little Rock hospital systems, and between systems and physicians, for facility dominance in individual specialty areas. This has strained relationships between hospital systems and their affiliated physicians, especially with respect to surgeons with ownership stakes in competing facilities. In the past, physician-owned specialty care facilities were perceived as threats to full-service community hospitals because of their potential to “skim” the highest-margin patients and procedures. Now, observers believe the threat posed by these physician-owned facilities may have been overstated. Reportedly the specialty hospitals are struggling financially, and the Arkansas Heart Hospital, owned by MedCath, is for sale.

Hospital-Physician Relations

![]() Hospital systems are seeking closer alignment with both specialists in key service lines and primary care physicians to gain referrals and tighten control over care delivery. Historically, Baptist and St. Vincent each have had organizations offering a variety of services, such as practice management, to community physicians. At present, the hospital systems are re-examining their physician alignment strategies but are not pursuing widespread employment of physicians. Instead, hospital acquisition of practices and employment of physicians are occurring in support of specific strategic initiatives. For instance, St. Vincent recently hired several members of the UAMS neurosurgery staff and is now promoting its strength as a neurosurgery center but lost about a dozen internists to Little Rock Diagnostic Clinic.

Hospital systems are seeking closer alignment with both specialists in key service lines and primary care physicians to gain referrals and tighten control over care delivery. Historically, Baptist and St. Vincent each have had organizations offering a variety of services, such as practice management, to community physicians. At present, the hospital systems are re-examining their physician alignment strategies but are not pursuing widespread employment of physicians. Instead, hospital acquisition of practices and employment of physicians are occurring in support of specific strategic initiatives. For instance, St. Vincent recently hired several members of the UAMS neurosurgery staff and is now promoting its strength as a neurosurgery center but lost about a dozen internists to Little Rock Diagnostic Clinic.

Respondents agreed that physicians, especially some specialists, such as cardiologists, are more interested in employment than they have been in the past. Overall, the pace of change in hospital-physician relationships in Little Rock seems relatively slow compared to other metropolitan areas. For example, primary care physicians are reportedly reluctant to enter into employment. Instead, some are focused on adding relatively lucrative ancillary services, such as sleep testing, to their practices or establishing new practice sites in relatively well-insured areas of Little Rock. The use of hospitalists also is growing as busy primary care physicians’ interest in making hospital rounds wanes.

Despite growing hospital interest in greater alignment with physicians, Little Rock physicians can still operate successful independent practices without exclusive ties to particular hospital systems. As one respondent said, hospital systems and physicians “see themselves as two entities that are sort of in the same playground but not in the same game.”

Pressure to Keep Premium Increases Down

![]() ll three leading health plans—ABCBS, QualChoice and UnitedHealth Group—face pressures from employers of all sizes to keep premium increases under control. Because the incomes of Little Rock residents are low relative to national averages, premium increases have a larger proportionate impact on them. Although Arkansas’ premium costs are lower than the national average, employers have become more price sensitive in recent years, with one health plan respondent observing, “The amount of savings an employer will leave you for has shrunk.” And, respondents also observed that employers can switch plans with fewer disruptions than in the past, because all plans sell similar PPO products and their provider networks are essentially the same. As one respondent said, “Everyone’s plans look kind of the same, honestly. It’s just so price sensitive.”

ll three leading health plans—ABCBS, QualChoice and UnitedHealth Group—face pressures from employers of all sizes to keep premium increases under control. Because the incomes of Little Rock residents are low relative to national averages, premium increases have a larger proportionate impact on them. Although Arkansas’ premium costs are lower than the national average, employers have become more price sensitive in recent years, with one health plan respondent observing, “The amount of savings an employer will leave you for has shrunk.” And, respondents also observed that employers can switch plans with fewer disruptions than in the past, because all plans sell similar PPO products and their provider networks are essentially the same. As one respondent said, “Everyone’s plans look kind of the same, honestly. It’s just so price sensitive.”

In the past, health plan offerings in Little Rock were distinguished by their provider networks. ABCBS long had an exclusive relationship with Baptist Health, a co-owner of the Blue’s HMO product, and QualChoice contracted exclusively with St. Vincent and UAMS, reflecting the two’s ownership stakes in the health plan.

The passage of state any-willing-provider legislation has “leveled the playing field” in this regard (see box below for more information). Baptist Health now is offered as part of the QualChoice PPO product, while ABCBS includes the other two systems in its PPO network. Respondents reported that this network expansion on the part of the competing health plans occurred relatively smoothly, despite predictions to the contrary.

One significant development has been the resurgence of QualChoice, which has added about 10,000 new enrollees annually in recent years, drawn primarily from local public-sector employers and mid-to-small-sized firms. The plan now has about 85,000 enrollees statewide, mostly in Central Arkansas.

Given the dominance of ABCBS, one respondent described the Little Rock health insurance market as “an 800-pound gorilla and the little players.” Another respondent observed that ABCBS benefits from the presence of QualChoice and United because they blunt purchaser and regulator concerns that the Blue plan could exercise near-monopoly power in the market.

Respondents generally agreed that ABCBS holds the upper hand in payment rate negotiations with providers, more so than the two smaller health plans. Hospitals generally have more leverage than physician groups, and hospitals have been able to garner rate increases.

Market observers expressed the view that Little Rock health plans have been relatively cautious—compared to plans in some other metropolitan areas—in introducing new products and services. Health plans reported that there has been only limited employer interest in consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs) linked to either a health savings account (HSA) or health reimbursement account (HRA), although this may be changing among smaller employers. Value-based insurance designs—in which copayments and coinsurance are structured to encourage the use of effective treatments and discourage the use of ineffective ones—are not present in Little Rock. A broker observed, “No one is asking for this. .We always seem to be last here.” Health plans have been hesitant to offer tiered-network products—which identify high-quality, lower-cost providers and provide incentives for health plan enrollees to seek care from them—for fear of provider unwillingness to participate if not classified in the most favorable tier. One large employer suggested that health plans were concerned that the Arkansas Medical Society, which has considerable political sway, would oppose these plans because they would differentiate among Arkansas physicians based on quality and costs.

All plans offer a standard array of disease management programs. Health and wellness programs are offered by most plans but are fairly rudimentary in their designs. While these programs may offer plan enrollees the opportunity to complete health risk assessments and access support for behavioral changes, they are not likely to include significant financial incentives. ABCBS, in particular, is perceived as “relatively conservative” in its approach to the use of incentives in health and wellness programs.

Impacts of Any-Willing Provider Legislation Any-willing provider legislation was implemented in Arkansas in 2005 to expand access to providers for privately insured consumers and to increase opportunities for providers to participate in multiple health plan networks. Prior to the law’s passage, ABCBS had an exclusive contracting arrangement with Baptist Health. Under the AWP law, providers can contract with any health plan in the state if they accept the plan’s contractual requirements. Since the AWP law was enacted, Baptist Health has become a provider in the networks of other health plans, and ABCBS has expanded its network to include other hospitals in Little Rock. While expansion of plan networks has occurred relatively smoothly for the most part, health plan contract negotiations with for-profit specialty hospitals have been contentious, to the extent that three specialty facilities, led by Arkansas Surgical Hospital, filed a complaint with the state Department of Insurance. The complaint argued that the any-willing provider law required health plans to pay them the same rates as general hospitals and urged disclosure of the rates plans pay to different providers. The plans argued that provider reimbursement rates always have been negotiated and should not be disclosed. The initial complaint was settled in favor of the health plans, but Arkansas Surgical Hospital pursued the complaint. In early 2011, the surgical hospital and ABCBS announced they had settled the dispute, and the state insurance commissioner issued an order on Jan. 7, 2011 dismissing the complaint. |

Anticipating Health Reform

![]() ittle Rock respondents had differing hopes and expectations regarding the impact of federal health care reform in their community. While some respondents opposed the imposition of a federal “solution” to the uninsured problem, others saw health reform as a potential boon for Little Rock, citing the large amount of federal dollars that could flow to Arkansas’ Medicaid program, to Little Rock health plans through the sale of more individual insurance products, and to providers through reductions in uncompensated care, as more people become insured. And, as already noted, health reform could dramatically reduce the number of people in Little Rock lacking health insurance and improve their access to care.

ittle Rock respondents had differing hopes and expectations regarding the impact of federal health care reform in their community. While some respondents opposed the imposition of a federal “solution” to the uninsured problem, others saw health reform as a potential boon for Little Rock, citing the large amount of federal dollars that could flow to Arkansas’ Medicaid program, to Little Rock health plans through the sale of more individual insurance products, and to providers through reductions in uncompensated care, as more people become insured. And, as already noted, health reform could dramatically reduce the number of people in Little Rock lacking health insurance and improve their access to care.

At the same time, some respondents were concerned about whether the Little Rock health system would be able to respond adequately to the increased demand for primary care resulting from demands of newly insured patients. For instance, hospital system respondents expected an increase in demand for care in their emergency departments as more people become insured and then have difficulty accessing primary care physicians. Others hoped that this increased demand would lead to state legislation expanding the scope of practice for mid-level practitioners. Even though reform has the potential to bring new federal dollars to the state, some respondents questioned whether the state’s tax base would be sufficient to generate the required state matching funds.

Issues to Track

- Will the coverage expansions resulting from health care reform worsen access to primary care, or will the advent of large numbers of newly covered residents stimulate efforts to address access problems?

- Will Little Rock hospital systems be successful in maintaining their role as statewide referral centers and furthering their expansion into more affluent and well-insured areas outside of Little Rock?

- How will relations between hospitals and physicians evolve? Will physician employment by health care systems grow more generally, as it has in other areas?

- How will employers and health plans respond to rising premiums? Will continued growth by QualChoice be a catalyst for innovation and competition in the health plan market?

- How will the state meet the looming Medicaid financing challenges, and can the state successfully gear up to enroll up to 250,000 new Medicaid enrollees covered as a result of health reform?

Background Data

| Little Rock Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Little Rock Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Population, 20091 | 485,488 | |

| Population Growth, 5-Year, 2004-20092 | 7.6% | 5.5% |

| Age3 | ||

| Under 18 | 25.3% | 24.8% |

| 18-64 | 62.9% | 63.3% |

| 65+ | 11.8% | 11.9% |

| Education3 | ||

| High School or Higher | 88.1% | 85.4% |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 25.9% | 31.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity4 | ||

| White | 71.0% | 59.9% |

| Black | 22.4%* | 13.3% |

| Latino | 3.6% | 18.6% |

| Asian | 1.3%# | 5.7% |

| Other Races or Multiple Races | 1.9% | 4.2% |

| Other3 | ||

| Limited/No English | 2.2% | 10.8% |

* Indicates a 12-site high. |

||

| Economic Indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Little Rock Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Individual Income less than 200% of Federal Poverty Level1 | 35.1% | 26.3% |

| Household Income more than $50,0001 | 45.3%# | 56.1% |

| Recipients of Income Assistance and/or Food Stamps1 | 10.1% | 7.7% |

| Persons Without Health Insurance1 | 14.6% | 14.9% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20082 | 4.5%# | 5.7% |

| Unemployment Rate, 20093 | 6.2%# | 9.2% |

| Unemployment Rate, May 20104 | 6.8% | 9.6% |

# Indicates a 12-site low. |

||

| Health Status1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Little Rock Metropolitan Area | Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||

| Asthma | 12.1% | 13.4% |

| Diabetes | 9.0% | 8.2% |

| Angina or Coronary Heart Disease |

5.1% | 4.1% |

| Other | ||

| Overweight or Obese | 62.4% | 60.2% |

| Adult Smoker | 23.4% | 18.3% |

| Self-Reported Health Status Fair or Poor |

15.3% | 14.1% |

Sources: |

||

| Health System Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Little Rock Metropolitan Area |

Metropolitan Areas 400,000+ Population | |

| Hospitals1 | ||

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population | 4.5* | 2.5 |

| Average Length of Hospital Stay (Days) | 5.5 | 5.3 |

| Health Professional Supply | ||

| Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 279 | 233 |

| Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Poplulation2 | 77 | 83 |

| Specialist Physicians per 100,000 Population2 | 202 | 150 |

| Dentists per 100,000 Population2 | 50 | 62 |

Average monthly per-capita reimbursement for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare3 |

$657 | $713 |

* Indicates a 12-site high.. Sources:1 American Hospital Association, 2008 2 Area Resource File, 2008 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians) 3 HSC analysis of 2008 county per capita Medicare fee-for-service expenditures, Part A and Part B aged and disabled, weighted by enrollment and demographic and risk factors. See www.cms.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/05_FFS_Data.asp. |

||

Community Reports are published by the Center for Studying

Health System Change:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org

President: Paul B. Ginsburg