HSC Research Brief No. 18

December 2010

Peter J. Cunningham

A key provision of the national health reform law is the creation of state-based exchanges to provide more affordable insurance options for people, especially the uninsured. Despite premium subsidies for people with incomes up to 400 percent of the poverty level, or $88,200 for a family of four in 2010, and an individual requirement to enroll in coverage, no one knows who will enroll in the exchanges and who will not, at least initially. Almost 40 percent of uninsured people eligible to receive subsidies through the exchanges have chronic conditions or report fair or poor health, and another 28 percent report recent problems with access to care or paying medical bills, according to a new national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). However, about one-third of uninsured people eligible for subsidies have had no recent problems with their health, access to medical care or paying medical bills. Enrolling these apparently healthy uninsured people is likely to be challenging but essential to avoiding adverse selection, or enrolling sicker-than-average people, in the exchanges. Otherwise, health insurance costs in the exchanges could be higher than expected.

Contrary to popular perception, many of these healthy and low-cost uninsured people view themselves as risk-averse, which could motivate them to gain coverage in the absence of health or access problems. Also, most uninsured people believe they need health coverage, although fewer believe that health insurance is currently worth the cost, a situation that could change once premium subsidies are available in 2014.

![]() ey provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 include the creation of state-based insurance exchanges and health insurance tax credits for people ineligible for employer-sponsored or public coverage.1 The credits, available in 2014, will make individual coverage purchased through the exchanges more affordable for people with incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty. The subsidies are designed so that, if a family enrolls in a lower-cost “silver” plan, its out-of-pocket spending on premiums will equal a certain percentage of family income, from just more than 3 percent at the lower end of the income range to 9.5 percent for those with incomes between 300 percent and 400 percent of poverty. The subsidies will markedly increase the affordability of health insurance for many people whose only option now is the nongroup, or individual, insurance market.

ey provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 include the creation of state-based insurance exchanges and health insurance tax credits for people ineligible for employer-sponsored or public coverage.1 The credits, available in 2014, will make individual coverage purchased through the exchanges more affordable for people with incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty. The subsidies are designed so that, if a family enrolls in a lower-cost “silver” plan, its out-of-pocket spending on premiums will equal a certain percentage of family income, from just more than 3 percent at the lower end of the income range to 9.5 percent for those with incomes between 300 percent and 400 percent of poverty. The subsidies will markedly increase the affordability of health insurance for many people whose only option now is the nongroup, or individual, insurance market.

In addition, the health reform law includes a requirement that most individuals obtain health insurance or pay a penalty. The so-called individual mandate—one of the law’s more controversial aspects—has been criticized both for being overly intrusive and for being too weak to effectively encourage enrollment. In 2016, when fully phased in, the penalty will equal the greater of a flat-dollar amount—$695 per uninsured adult and half that amount for uninsured children—or 2.5 percent of family income. For many currently uninsured people, the penalty would be less than the after-subsidy premium they would pay for a low-cost exchange plan, so some will decide to pay the penalty instead of enrolling in coverage.

While the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that 8 million people will purchase their own coverage through the exchanges in 2014, growing to 24 million by 2019,2 it is difficult to predict how many eligible people will actually enroll, the speed at which they will enroll, and the characteristics of those who enroll vs. those who opt out and remain uninsured. Aside from the financial incentives included in the law, people’s motivation to enroll will depend on many factors. These include the demand for medical care among potential enrollees, which reflects not only their health status and prevalence of chronic diseases, but also their attitudes and propensity to use services when sick, and the availability of free or discounted care through the health care safety net or other providers. Regardless of demand, uninsured people and others who have had recent problems affording or accessing care because they lack coverage or have inadequate coverage also will have motivation to enroll in the exchanges. Similarly, more subtle attitudes about the value and importance of health insurance and willingness to incur the financial risk of going without coverage also will influence decisions to enroll.

This study describes the population that will be eligible to receive premium subsidies through the new insurance exchanges—gross family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty—focusing on the uninsured who currently have no access to employer-sponsored coverage and who will be ineligible for expanded Medicaid coverage.3 The analysis focuses on the subsidy-eligible uninsured because the availability of premium subsidies will affect their insurance choices and decisions to a greater extent than uninsured people above 400 percent of the poverty level, who can purchase coverage through the exchanges but will not receive subsidies.

![]() mong adults who meet the income-eligibility requirements to receive subsidies through the exchanges and who will be ineligible for the Medicaid expansions (incomes between 138%-400% of poverty), almost 80 percent were enrolled in some type of health coverage in 2007, while 20.8 percent were uninsured (see Data Source and Table 1). Most (62.1%) had employer-sponsored insurance, while 6.4 percent had nongroup coverage and 10.7 percent had some type of public coverage, such as Medicaid or Medicare.

mong adults who meet the income-eligibility requirements to receive subsidies through the exchanges and who will be ineligible for the Medicaid expansions (incomes between 138%-400% of poverty), almost 80 percent were enrolled in some type of health coverage in 2007, while 20.8 percent were uninsured (see Data Source and Table 1). Most (62.1%) had employer-sponsored insurance, while 6.4 percent had nongroup coverage and 10.7 percent had some type of public coverage, such as Medicaid or Medicare.

Among the income-eligible uninsured, about one in five had access to employer coverage, either through their own job or a spouse’s job (findings not shown). People with access to employer coverage generally will not be eligible for the exchanges unless their employer coverage does not meet the affordability standards defined in the law. To the extent these individuals enroll in coverage once the employer and individual mandates take effect in 2014, most will likely enroll in the coverage offered by their employers, because they or their spouses work for larger employers (50 or more workers) who will be required to offer coverage or pay a penalty (see Supplementary Table 1).

Most subsidy-eligible uninsured people do not have access to employer coverage, and most will continue to lack access to employer coverage following implementation of health reform because they are self-employed or work in small firms (41.5%) or are unemployed (40.7%). Most people who currently have nongroup coverage and will be eligible for premium subsidies are likely to shift their coverage to the exchanges, since the subsidies will lower premium costs for most.

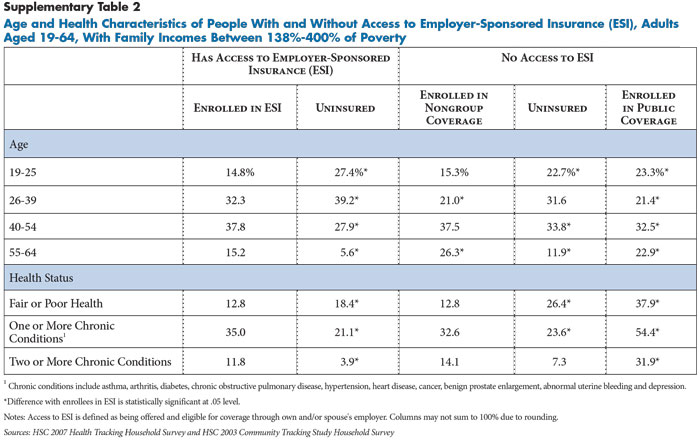

People already enrolled in nongroup coverage are older and have higher rates of chronic disease prevalence than the uninsured, reflecting the greater demand for insurance among people with health problems (see Supplementary Table 2). Nevertheless, chronic disease prevalence among those in nongroup coverage is similar to those currently enrolled in employer coverage. Prevalence of chronic diseases is lower among the uninsured compared to both groups of privately insured.

![]() any uninsured people eligible to receive subsidies on the exchanges will be motivated to enroll either because of their high need for medical care or because they recently experienced problems accessing care or paying medical bills. Overall, about 40 percent of uninsured people eligible to receive subsidies through the exchanges had chronic conditions or reported their health as fair or poor (see Table 2). Many of these individuals also reported not getting or delaying needed medical care in the past year (65.7%) or problems paying medical bills (53.6%), providing additional motivation to enroll in health insurance (findings not shown). They also on average spent almost $1,000 out of pocket on medical care in the year prior to the survey.

any uninsured people eligible to receive subsidies on the exchanges will be motivated to enroll either because of their high need for medical care or because they recently experienced problems accessing care or paying medical bills. Overall, about 40 percent of uninsured people eligible to receive subsidies through the exchanges had chronic conditions or reported their health as fair or poor (see Table 2). Many of these individuals also reported not getting or delaying needed medical care in the past year (65.7%) or problems paying medical bills (53.6%), providing additional motivation to enroll in health insurance (findings not shown). They also on average spent almost $1,000 out of pocket on medical care in the year prior to the survey.

An additional 28.2 percent of uninsured people eligible for subsidies reported excellent or good health and no chronic conditions but did report problems getting needed medical care or problems paying medical bills in the past year. Although the survey data do not indicate the reasons or medical conditions related to their access and medical bill problems, they spent almost $1,400 out of pocket on medical care in the past year. Even if the health problems that generated these expenses were related to injuries or acute problems that are more time-limited, their experiences with access to care and medical bills are likely to provide motivation to enroll in coverage.

About one-third of uninsured people eligible for subsidies have no health, access or medical bill problems, and they spent only about $156 out of pocket on medical care in the past year. These “healthy” uninsured people tend to be younger than other uninsured people. Their participation in the exchanges is important to preventing adverse selection, although they may be the most challenging to enroll because they have no immediate need for medical care or negative experiences to motivate them to enroll. They also have somewhat higher incomes compared to uninsured people with health, access or medical bill problems, meaning that the premium subsidies will be less generous relative to their income compared to lower-income, uninsured people. This gives them more of a financial incentive to pay the penalty rather than enroll in coverage.

Additionally, there are two provisions in the health reform law that may steer younger, healthy people away from the exchanges, potentially raising the risk of adverse selection in the exchanges. The first is a provision that allows adult children to remain on their parents’ insurance until age 26. The second allows insurers to offer catastrophic plans for people under age 30 or those who receive an affordability exemption from the individual mandate.5

![]() espite being young and healthy, the one-third of uninsured people eligible for subsidies but without any health, access or medical bill problems are just as likely to be risk-averse as uninsured people with health problems. This is important because previous studies have found that people’s perceived willingness to take more risks than the average person is strongly related to their decision to opt out of employer-sponsored coverage, despite the fact that such coverage is heavily subsidized.6 Based on the same measure included in this earlier research, about half of the healthy uninsured people considered themselves to be risk-averse—statistically no different than uninsured people with health problems. This finding suggests that many of the young and healthy uninsured do not feel as invincible as is commonly assumed and—given affordable premiums—they would be willing to pay for coverage they don’t immediately need to avoid catastrophic costs in the future. One factor, perhaps, contributing to their risk-averseness is that many healthy uninsured people also have uninsured family members (41.9%), including spouses and/or children. Providing health coverage for children and spouses may be an additional motivator for individuals who might otherwise not be motivated enough to purchase coverage for just themselves.

espite being young and healthy, the one-third of uninsured people eligible for subsidies but without any health, access or medical bill problems are just as likely to be risk-averse as uninsured people with health problems. This is important because previous studies have found that people’s perceived willingness to take more risks than the average person is strongly related to their decision to opt out of employer-sponsored coverage, despite the fact that such coverage is heavily subsidized.6 Based on the same measure included in this earlier research, about half of the healthy uninsured people considered themselves to be risk-averse—statistically no different than uninsured people with health problems. This finding suggests that many of the young and healthy uninsured do not feel as invincible as is commonly assumed and—given affordable premiums—they would be willing to pay for coverage they don’t immediately need to avoid catastrophic costs in the future. One factor, perhaps, contributing to their risk-averseness is that many healthy uninsured people also have uninsured family members (41.9%), including spouses and/or children. Providing health coverage for children and spouses may be an additional motivator for individuals who might otherwise not be motivated enough to purchase coverage for just themselves.

![]() ome also contend that many people are uninsured by choice because they do not value health insurance and prefer to spend income on other goods and services rather than on health insurance premiums. To examine differences in attitudes about health insurance between uninsured and insured people, this study examined data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: (1) “I’m healthy enough that I don’t need health insurance;” and (2) “Health insurance is not worth the money that it costs.”

ome also contend that many people are uninsured by choice because they do not value health insurance and prefer to spend income on other goods and services rather than on health insurance premiums. To examine differences in attitudes about health insurance between uninsured and insured people, this study examined data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: (1) “I’m healthy enough that I don’t need health insurance;” and (2) “Health insurance is not worth the money that it costs.”

In general, the findings indicate that uninsured people without access to employer coverage value health insurance coverage less than insured people. Uninsured people were more likely to agree that they were healthy enough that they didn’t need health insurance and that health insurance wasn’t worth the cost, compared with people with employer coverage (see Table 3). Despite these differences, most uninsured people—more than 60 percent—disagreed with the view that they do not need health insurance coverage, with more than 40 percent strongly disagreeing. However, a smaller percentage of uninsured people—about 41 percent—disagreed that health insurance is not worth the cost, indicating more ambivalence about the value of health insurance coverage.

This ambivalence is especially apparent among people with nongroup coverage. On the one hand, they are similar to people with employer coverage in that most believe they need health insurance. On the other hand, they are more likely than both uninsured and those with employer coverage to believe that health insurance is not worth the cost. Because premiums for nongroup coverage currently are not subsidized, this seemingly contradictory view likely reflects the very high costs that enrollees pay for nongroup coverage.

Uninsured people are more likely to disagree that that they do not need health insurance coverage if they are older, have chronic conditions, have had negative experiences with access to care in the past year, and have incurred out-of-pocket spending greater than 5 percent of their income (see Table 4). However, even among groups with relatively low need, such as younger people or those without chronic conditions or access problems, most believe they need health insurance.

There is less variation among uninsured people in their assessment of whether health insurance coverage is worth the cost. For example, there was no statistically significant difference between those with and without chronic conditions in the proportion that disagreed that health insurance is not worth the cost. This ambivalence between the perceived “need” for health insurance coverage and the perceived “value” of such coverage likely reflects the fact that current insurance options are unaffordable for lower-income, uninsured people without access to employer coverage. In sum, these findings suggest that cost and affordability influence the decision not to purchase coverage for most uninsured people rather than perceptions that health insurance coverage isn’t necessary.

![]() he individual mandate is one of the most controversial aspects of health reform. Critics believe that the federal government should not require people to purchase insurance. Advocates contend a mandate—in conjunction with requiring insurers to discontinue medical underwriting—is essential to prevent adverse selection in the exchanges caused by young and healthy individuals opting out. However, the importance of the individual mandate to enrollment may be overstated. Enrollment decisions will still be guided by whether subsidized coverage is affordable and by whether the expected benefits of insurance coverage outweigh the cost to the individual. Many uninsured people with substantial health needs will enroll because the premium subsidies in the exchanges will substantially lower their health care costs and improve their access to care.

he individual mandate is one of the most controversial aspects of health reform. Critics believe that the federal government should not require people to purchase insurance. Advocates contend a mandate—in conjunction with requiring insurers to discontinue medical underwriting—is essential to prevent adverse selection in the exchanges caused by young and healthy individuals opting out. However, the importance of the individual mandate to enrollment may be overstated. Enrollment decisions will still be guided by whether subsidized coverage is affordable and by whether the expected benefits of insurance coverage outweigh the cost to the individual. Many uninsured people with substantial health needs will enroll because the premium subsidies in the exchanges will substantially lower their health care costs and improve their access to care.

For uninsured people with few foreseen health needs, however, it may, depending on their income, be considerably less expensive to pay the penalty than enroll in private insurance. Getting these uninsured people to enroll—which is crucial to avoiding adverse selection in the exchanges—will depend on their receptiveness to the idea that insurance coverage has value because of long-term financial protection and enhanced access to care, even if they experience little short-term gain. The study findings suggest that the perception among some that most uninsured people do not value coverage and are willing to risk incurring catastrophic costs is overstated, although ultimately whether they enroll will depend on whether these perceived benefits are equal to or greater than the subsidized premiums they pay.

There is also likely to be substantial regional and geographic variation in enrollment levels in exchanges, as is the case with uninsured rates more generally. Many point to the success of Massachusetts’ health reform—upon which many PPACA provisions are based—in reducing the uninsured rate in half in that state.7 However, a crucial difference between Massachusetts and the rest of the nation is that uninsured rates in Massachusetts have always been among the lowest in the nation, in part because of a strong culture of insurance coverage among employers, the state government and the population in general. It is questionable whether the success of Massachusetts could be easily replicated in areas of the country where uninsured rates have been high historically and public resistance to national health reform—especially the individual mandate—is greater.

Outreach efforts to increase enrollment and streamlining enrollment procedures will be crucial to the success of the exchanges, just as they have been to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). And, there are a number of provisions in the health reform law that address enrollment and outreach activities, such as the use of Web portals and navigators to provide information and advise consumers on insurance options. However, outreach and enrollment activities in the exchanges will require a different approach than for Medicaid and CHIP, since Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment are often determined at the point of service when people actually need care. Rather, outreach activities in the exchanges will have the much more daunting challenge of ensuring sufficient enrollment of healthy and low-cost uninsured persons who have little or no contact with the health care system but would be expected to pay more than a nominal premium amount.

Designating defined open-enrollment periods in the exchanges will help reduce the adverse selection created when people can wait to enroll until they need care. Continuous open enrollment has been cited as a contributor to adverse selection in the combined small and nongroup health insurance market in Massachusetts.8 The federal health reform law requires the exchanges to provide an initial open-enrollment period, as well as annual and special open-enrollment periods similar to Medicare Part D, although the timing and length of the enrollment periods will be determined through regulation. Efforts to educate the public about the exchanges during open-enrollment periods should stress not only the financial penalties associated with the individual mandate, but also the much greater access to medical care that comes with insurance coverage and the personal financial risk of going without coverage if they incur unexpected medical costs. The study findings suggest that even most of the “young and healthy” uninsured will be receptive to this message.

This Research Brief is based on two nationally representative household surveys. Estimates of insurance coverage were obtained from the 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey (HTHS), a nationally representative telephone survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The sample for the survey includes about 18,000 persons in total, and 4,500 persons between 19-64 years of age with family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty. Analysis of the population eligible to receive subsidies in the insurance exchanges combines the 2007 HTHS with the 2003 Community Tracking Study Household Survey. The combined sample for uninsured persons 19-64 years of age, family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty, and no access to employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) is about 2,100 persons. Both surveys use the same questionnaire and data collection procedures. Population weights adjust for the probability of selection and differences in nonresponse based on age, sex, race or ethnicity, and education.

Estimates of attitudes toward health insurance coverage are based on the 2005-2007 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component (MEPS-HC) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS is also designed to be nationally representative of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. The combined sample for the 2005-2007 surveys for persons 19-64 years of age with family incomes between 138 percent and 400 percent of poverty is about 20,000, which includes 3,250 uninsured persons with no access to ESI coverage.

According to the PPACA, eligibility for premium subsidies is restricted to U.S. citizens and legal immigrants. Ideally, the analysis should exclude unauthorized immigrants as they are not eligible to receive subsidies in the exchanges. However, unauthorized immigrants cannot be identified explicitly on either the HTHS or MEPS, and it is likely that they are underrepresented in the HTHS because the sample is based on a random selection of landline telephone numbers. To at least partially account for the presence of unauthorized immigrants in the HTHS, the analysis excludes noncitizens who have characteristics that are known to be highly correlated with being an unauthorized immigrant.4 This includes a combination of being in the U.S. for less than 20 years, not having any type of public insurance coverage (which they are generally not eligible for), having less than a high school education and working in such industries as agriculture, construction, manufacturing, hotels, personal services and restaurants. It was not feasible to simulate the unauthorized population in the MEPS because there is no information on citizenship for sampled persons.

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.