HSC Research Brief No. 14

November 2009

Elizabeth A. November, Genna R. Cohen, Paul B. Ginsburg, Brian C. Quinn

Individual insurance is the only source of health coverage for people without

access to employer-sponsored insurance or public insurance. Individual insurance

traditionally has been sought by older, sicker individuals who perceive the

need for insurance more than younger, healthier people. The attraction of a

sicker population to the individual market creates adverse selection, leading

insurers to employ medical underwriting—which most states allow—to

either avoid those with the greatest health needs or set premiums more reflective

of their expected medical use. Recently, however, several factors have prompted

insurers to recognize the growth potential of the individual market: a declining

proportion of people with employer-sponsored insurance, a sizeable population

of younger, healthier people forgoing insurance, and the likelihood that many

people receiving subsidies to buy insurance under proposed health insurance

reforms would buy individual coverage. Insurers are pursuing several strategies

to expand their presence in the individual insurance market, including entering

less-regulated markets, developing lower-cost, less-comprehensive products targeting

younger, healthy consumers, and attracting consumers through the Internet and

other new distribution channels, according to a new study by the Center for

Studying Health System Change (HSC). Insurers’ strategies in the individual

insurance market are unlikely to meet the needs of less-than-healthy people

seeking affordable, comprehensive coverage. Congressional health reform proposals,

which envision a larger role for the individual market under a sharply different

regulatory framework, would likely supersede insurers’ current individual

market strategies.

![]() ypically, the individual insurance market serves people

seeking health coverage who do not have access to the group market through an

employer or who are ineligible for public insurance. These people include the

self-employed, those between jobs and the jobless, those employed by firms that

do not offer insurance, some part-time workers, and retirees too young to qualify

for Medicare who lack access to employer-sponsored retiree coverage.1

ypically, the individual insurance market serves people

seeking health coverage who do not have access to the group market through an

employer or who are ineligible for public insurance. These people include the

self-employed, those between jobs and the jobless, those employed by firms that

do not offer insurance, some part-time workers, and retirees too young to qualify

for Medicare who lack access to employer-sponsored retiree coverage.1

The current structure of the individual insurance market poses challenges for both insurers and consumers. Insurers offering individual coverage must deal with the problem of adverse selection, or disproportionately attracting sicker and costlier-to-cover individuals,2 which drives up the cost of coverage. (see Glossary of Insurance Terms and Concepts). To limit adverse selection, insurers use medical underwriting, or information about a person’s health status to set premiums and the scope of coverage, which in turn poses challenges for consumers, including:

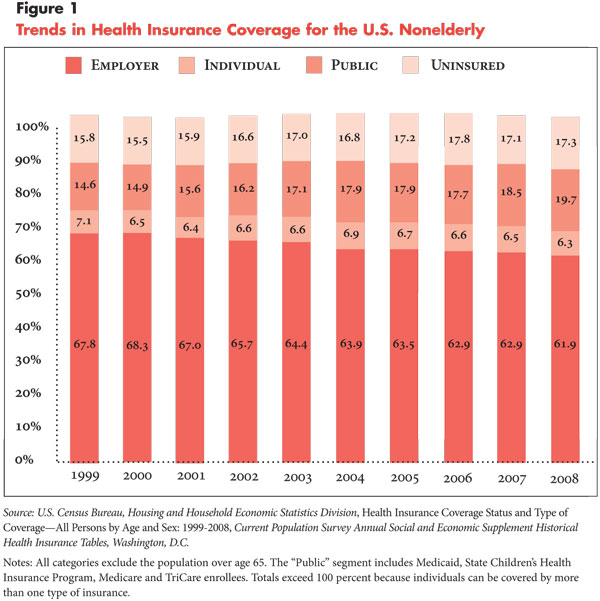

![]() ver the last decade, the proportion of nonelderly Americans

with individual insurance has hovered between 6 percent and 7 percent (see Figure

1), even as the proportion of people with employer-sponsored insurance has

declined. At the same time, the proportion of people with public insurance has

increased, while the rate of uninsured has grown.

ver the last decade, the proportion of nonelderly Americans

with individual insurance has hovered between 6 percent and 7 percent (see Figure

1), even as the proportion of people with employer-sponsored insurance has

declined. At the same time, the proportion of people with public insurance has

increased, while the rate of uninsured has grown.

Nevertheless, several factors have prompted insurers to view the individual market as a growth opportunity. A substantial portion of the individual insurance market in most states is held by Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) plans,4 in part because of their longevity in the market, and, in some cases, their mission to insure those who might otherwise be uninsurable or a state requirement to serve as insurer of last resort. Insurers entering the individual market seek to capture both market share and entice healthier individuals from BCBS plans and other competitors. Second, continuing economic pressures could push more people to seek individual coverage, such as reductions by employers in dependent coverage, employee layoffs and the availability of cheaper alternatives to group coverage. Third, as group coverage stagnates, insurers recognize that attracting new business, primarily young, healthy people, is critical to growth. Lastly, insurers recognize that national health reform could reshape the individual insurance market, with major reform proposals calling for subsidies and significant regulatory changes that could expand the market’s role in covering uninsured Americans.

Despite the increased focus on the individual market by insurers and policy makers, the community-level perspective on the individual market remains underexplored. This study examined the individual insurance markets in the 12 Community Tracking Study communities (see Data Source). The findings suggest that insurers, working within a patchwork of state regulations governing various aspects of the individual market, are responding to the potential of the individual market in several ways. They are entering markets with less-restrictive regulatory environments, offering lower-cost products, and pursing marketing strategies that underscore consumer shopping convenience and target particular groups of potential consumers.

![]() n the 12 communities, the individual insurance market tends to be dominated by mainstream insurers—those whose greatest portion of business is in the group market as opposed to the individual market. Typically, a BCBS plan holds the greatest market share. In about half of the markets, specialized insurers—those focusing on the sale of nongroup policies—are among the top three competitors.

n the 12 communities, the individual insurance market tends to be dominated by mainstream insurers—those whose greatest portion of business is in the group market as opposed to the individual market. Typically, a BCBS plan holds the greatest market share. In about half of the markets, specialized insurers—those focusing on the sale of nongroup policies—are among the top three competitors.

Competition greatest in less-regulated states. The individual insurance market is regulated at the state level, and regulations vary widely across the country. Key regulations regarding individual insurance pertain to the scope of insurers’ underwriting and product pricing, as well as their ability to limit access to coverage (see Table 1). A state’s regulatory environment creates a climate that is more or less welcoming to insurers and protective of consumers.

In an effort to ensure that consumers with high-risk health conditions have access to comprehensive coverage with some price protections, some states have enacted a combination of the following regulatory controls:

These constraints limit the ability of insurers to offer lower-priced products that would be attractive to healthier individuals—that is, products with less-comprehensive benefits or more-individualized rates. However, insurers in states with more regulatory constraints attract an adverse selection of applicants, making coverage prohibitively expensive for most consumers and limiting the size of the individual market.

In the markets studied with the most-restrictive regulatory environments—Boston, northern New Jersey, Seattle and Syracuse—respondents observed that fewer insurers are interested in competing for individual business. In these markets, individual products are offered almost exclusively by mainstream insurers, and new market entrants have been few in recent years. In Syracuse, for example, the combination of regulatory restrictions and state expansion of public programs has made the individual market the last resort for high-risk individuals. Insurers see the individual market as undesirable and do little to compete for the business. Similarly, in Seattle, the regulatory environment is a deterrent to new insurers entering the market. According to a local respondent, “For [insurers] to enter a market is pretty expensive—to do the research, get licensure, and get product approval. [Washington] never ends up on their top priority list [of markets to enter].”

Conversely, states with regulatory environments that allow insurers greater flexibility in screening applicants, pricing and product designs typically have a combination of the following:

Under these circumstances, insurers can control costs generally by excluding high-risk applicants and offering lower rates through the use of elimination riders and ratings based on individual characteristics, such as age, gender and health status. More lenient rating restrictions and fewer benefit mandates give insurers the freedom to offer products with different benefit levels at varying price points. Generally, these factors disadvantage the sickest consumers, while allowing for products that have greater appeal to healthier consumers. Study markets with less-restrictive regulatory environments—Cleveland, Greenville, Little Rock and Phoenix—have seen the greatest number of new entrants in the individual market in recent years and a greater diversity of insurers, including mainstream and specialized insurers.

Mainstream insurers situated to capitalize on potential individual business. Most of the new entrants in recent years are mainstream insurers that already offer coverage in the group market. As such, these insurers appear well situated to help transition individuals enrolled in their group products to their individual products. For example, as several insurer respondents observed, insurers that offer group coverage can assist employers seeking to transition their employees to individual coverage, as well as employees seeking lower-cost alternatives to employer-sponsored coverage. And, insurers that provide group student health insurance can help transition former students to individual policies. As an insurer respondent noted with regard to small employers dropping employee coverage: “The employers were tired of dealing with price increases and probably raised employee salaries and said ‘You’re on your own’ [to buy your own insurance]. We think that’s a place where we need to pay more attention to develop more options for those employers—perhaps a worksite-sold individual service.”

For several insurers, mainstream and specialized, entry into new markets appears

to be part of a national strategy to develop their presence in the individual

market. Across multiple communities, several national mainstream insurers—notably

UnitedHealthcare, Humana and Aetna—were expanding individual insurance

market products. While Humana and Aetna appeared to be doing this by building

on their existing presence as group insurers, UnitedHealth Group has developed

its individual line of business in part by acquiring two insurers with significant

national presence that specialize in individual and small-group products—Golden

Rule and American Medical Security Group Inc.5 To a lesser

extent, there is some entry by specialized insurers—namely Assurant and

American Community Mutual Insurance Company.

![]() onsumers in the individual insurance market, being highly

price conscious, seek lower-priced products. Acknowledging this demand, insurers

have pursued a variety of strategies to offer low-cost products. The most prevalent

strategy has been to expand offerings for high-deductible health plans (HDHP)

and limited-benefit products, which represent different approaches to cost savings.

HDHPs typically lack first-dollar coverage but provide financial protection

against catastrophic medical events. Limited-benefit products often offer first-dollar

coverage for some services but typically do not cover major medical expenses.

onsumers in the individual insurance market, being highly

price conscious, seek lower-priced products. Acknowledging this demand, insurers

have pursued a variety of strategies to offer low-cost products. The most prevalent

strategy has been to expand offerings for high-deductible health plans (HDHP)

and limited-benefit products, which represent different approaches to cost savings.

HDHPs typically lack first-dollar coverage but provide financial protection

against catastrophic medical events. Limited-benefit products often offer first-dollar

coverage for some services but typically do not cover major medical expenses.

Limited-benefit products are thought to be especially attractive to healthier individuals who do not envision incurring major medical expenses and want more useable benefits “up front,” sometimes not appreciating the consequences of failing to insure against a catastrophic event. Typically, insurers offer a range of products with different deductibles and benefits, although product offerings were more restricted in states requiring standardized individual insurance products, such as Massachusetts and New Jersey.

High-deductible offerings. High-deductible products were among the most popular individual products offered by insurers. Insurer and broker respondents indicated that consumers are gravitating toward the HDHP option with annual deductibles ranging from $1,000 to $3,000 and a lower coinsurance responsibility after the deductible has been reached; the 20 percent coinsurance level is popular.

In recent years, insurers have begun to expand their HDHP products, either by including a health savings account (HSA) option or offering preventive benefits that would attract a healthier population. According to respondents, HDHPs eligible for an HSA were among the fastest growing individual products. Consumers purchase these products because they are among those with the lowest price points, even though many, in fact, do not open or fund an account.

As for preventive care offerings, insurers reported a recent emphasis on individual insurance products that encourage well-care visits and screening for early detection of common diseases. There was little consistency in how insurers structured these benefits. Most common were products that allowed a limited number of office visits, typically between two and six visits annually, before the deductible applied and often with a copayment. According to respondents, products that include first-dollar coverage of screening tests, such as pap and cholesterol tests, were available in several markets. The addition of preventive care benefits to HDHPs was thought to attract healthier consumers who would otherwise forgo coverage because of the lack of apparent benefit to be gained for the cost.

Limited-benefit offerings. Insurers in a number of the 12 markets reported an increase in new or soon-to-be introduced products with limited-benefit designs. Insurer respondents consistently indicated the impetus for these products was the recognition that consumers shopping for individual insurance based on price would be particularly interested in lower-cost, limited-benefit products.

Insurers’ limited-benefit offerings take many forms. The most commonly reported benefit restriction was on prescription drugs—either limiting coverage to generics or excluding drug coverage altogether. To a lesser extent, insurers’ exclusions applied to particular procedures (such as tonsillectomies and chemotherapy) and tests (such as imaging and laboratory services) or limited the number of covered office visits. Several insurers’ limited-benefit products combine several techniques for lowering premiums, typically reducing benefits while increasing copayments or deductibles.

Across markets, respondents’ comments reflected the ongoing debate about the usefulness of limited-benefit products. Some contended that they offer consumers inadequate protection, while others saw the products as a way of providing consumers an affordable alternative to more comprehensive coverage. A state official’s comment illustrates both sides: “People look first at the premium, then the deductible. Most people are healthy and don’t have immediate need for services and don’t have the ability to evaluate the potential promise of the product. Once they use the product and become aware of these very significant limitations, they become unhappy. But there is a group of people paying low premiums [who have remained healthy] who think they have a good deal.”

The absence of limited-benefit product offerings in some markets suggests concerns by insurers and policy makers about the potential fallout from these products, such as when consumers who become seriously ill find themselves without adequate financial protection from large medical bills. In some markets where regulation permits limited-benefit products, such as Little Rock, insurers, nevertheless, are reluctant to offer them. In other markets, such as Seattle, insurers have shown interest in offering limited-benefit products but have been unable to do so because of regulatory barriers.

![]() raditionally, insurers’ marketing strategies have relied on internal sales staff or agents and insurance brokers to make in-person sales. Insurers used broad marketing campaigns—usually television, print and radio advertising or direct mailings—that capitalized on brand-name recognition. Today, however, the Internet fosters insurers’ departure from traditional advertising and sales methods, increasingly toward direct sales to consumers. The Internet also facilitates segmented marketing—targeting products to consumer subpopulations—to address individual consumer preferences.

raditionally, insurers’ marketing strategies have relied on internal sales staff or agents and insurance brokers to make in-person sales. Insurers used broad marketing campaigns—usually television, print and radio advertising or direct mailings—that capitalized on brand-name recognition. Today, however, the Internet fosters insurers’ departure from traditional advertising and sales methods, increasingly toward direct sales to consumers. The Internet also facilitates segmented marketing—targeting products to consumer subpopulations—to address individual consumer preferences.

Respondents from nearly all sites reported increased reliance on the Internet as a tool for marketing and selling individual insurance products, though insurers used the Internet to varying degrees. Many have developed the capacity to accept applications online. Some rely on ehealthinsurance.com—which serves both as a platform for comparison shopping across insurers and an online insurance broker. A few insurers have restricted their Internet presence to displaying product information or providing tools to help consumers comparison shop. Generally, insurer respondents expressed interest in further developing their online sales capabilities, in part seeing them as a cost-effective way to sell products.

Despite the potential marketing and sales advantages afforded by the Internet, some respondents raised concerns that the removal of sales staff from the process could result in less-informed purchasing decisions by consumers. Without a broker’s assistance to guide applicants’ insurer and product selections, consumers applying online may not know which products best suit their needs, particularly if insurers do not make all of their products available online. Further, inadvertent mistakes in the application process can have severe ramifications, as exemplified by the recent controversy over insurers’ rescission, or retroactive cancellation, of policies because of allegedly misreported medical histories.6 While online applications can be designed to safeguard against some errors, such as preventing the submission of incomplete applications, it remains to be seen whether this distribution channel affects the accuracy of applications.

Although insurer respondents generally indicated a continued commitment to the use of brokers, changes to the brokers’ role were underway. One insurer respondent noted, “Some competitors are dis-intermediating their business, but we don’t think there is a simple program that can be sold without a broker. [Looking ahead] our approach will have to be more conducive to individuals investigating on the Internet and getting them in touch with a broker to help understand [the product] instead of relying on the broker to present the product to the person.” Respondents indicated that brokers were submitting applications for their customers online through insurer Web sites or setting up their own sites to capture Internet shoppers, suggesting they were adapting to the technological shift.

Respondents in a majority of sites indicated a recent shift toward segmented marketing. Commonly targeted subpopulations include the young and healthy, and to a lesser extent, small business owners, early retirees, and racial or ethnic groups. While approaches to segmented marketing take many forms, including on-site promotions at venues frequented by certain groups and direct mailings, the Internet holds great potential as a platform for targeted marketing. Respondents noted that Web sites can be designed for, and e-mail advertisements targeted to, special consumer groups. For example, several insurer respondents cited their efforts to develop Web sites attractive to young, healthy consumers—a strategic move given the affinity of younger consumers for Web-based transactions. For some insurers, segmented marketing represents a departure from insurers’ reliance on reputation, or brand marketing, to help sell their products.

![]() he individual health insurance market has long been challenging for both insurers and consumers, as insurers seek to develop and distribute products in ways that limit adverse selection and consumers search for affordable, comprehensive coverage. State regulators also face a choice between fostering insurer competition through minimal regulatory restrictions and protecting consumers who have the greatest need for insurance. Nevertheless, insurers have been investing more in the individual market in response to the erosion of the employer-based insurance market and the potential for national health reform. Large group insurers, which are poised to capitalize on these shifts, have increasingly entered the individual market. In other changes, insurers are focusing on offering lower-cost benefit structures and targeting lower-risk populations in less-regulated markets. This new focus, while appealing to healthy consumers, may fail to provide adequate coverage for these products’ purchasers over time and may make individual insurance products inaccessible to those with the greatest health needs.

he individual health insurance market has long been challenging for both insurers and consumers, as insurers seek to develop and distribute products in ways that limit adverse selection and consumers search for affordable, comprehensive coverage. State regulators also face a choice between fostering insurer competition through minimal regulatory restrictions and protecting consumers who have the greatest need for insurance. Nevertheless, insurers have been investing more in the individual market in response to the erosion of the employer-based insurance market and the potential for national health reform. Large group insurers, which are poised to capitalize on these shifts, have increasingly entered the individual market. In other changes, insurers are focusing on offering lower-cost benefit structures and targeting lower-risk populations in less-regulated markets. This new focus, while appealing to healthy consumers, may fail to provide adequate coverage for these products’ purchasers over time and may make individual insurance products inaccessible to those with the greatest health needs.

The Internet has somewhat altered insurers’ marketing strategies and reduced the role of independent brokers. The shift to direct sales through the Internet underscores the growing role of consumers in assessing their health insurance options; despite these conveniences, consumers leaving group coverage may face challenges in selecting products as they adjust their expectations to the dynamics of the individual market. Furthermore, products selected based on inadequate information online or misunderstanding of the individual market may ultimately lead to consumer dissatisfaction.

National health reform could radically transform the individual insurance market. Current reform proposals include subsidies for lower- and moderate-income people to buy insurance, creation of insurance exchanges and much stricter regulation of the individual market. Proposed regulatory changes include a mandate for individuals to be covered, guaranteed-issue requirements, a ban on medical underwriting, use of modified community rating and products standardized by actuarial value, or the covered medical expenses estimated to be paid by the insurer.

With these changes, the market could become an order of magnitude larger, and products would likely be more similar to those available in the group market. For insurers, a mandate requiring individuals to purchase insurance would be key to protecting against adverse selection. For consumers, the most important change would be a market designed to provide comprehensive, affordable products to those in poor health as well as those in good health. Some of the strategies that insurers have pursued to date will be applicable to such a reformed market, but others, such as limited-benefit products, would likely disappear.

To examine insurers’ strategies in the individual health insurance

market and changes in states’ regulatory environments related to individual

insurance, information was collected from the 12 communities that are part of

the Community Tracking Study—Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis;

Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County,

Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. In each of these communities, interviews

were conducted with one to three insurance executives, including a representative

from the local Blue Cross Blue Shield plan(s); an insurance broker; and a representative

from the state insurance commissioner’s office. Representatives of state

health plan associations and consumer advocacy organizations were also interviewed,

along with representatives of two national health plans and three national associations

representing the insurance industry and insurance brokers. Additionally, respondents

who provided national perspectives on individual health insurance were interviewed.

The findings are based on 72 semi-structured phone interviews conducted by two-person

interview teams between August and December 2008. Atlas.ti, a qualitative software

package, was used to analyze the interview data.

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

RESEARCH BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System

Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org