Alabama’s Pass on Medicaid Expansion Leaves Birmingham’s Uninsured with Weak Safety Net

RWJF Reform Community Report

October 2013

Ha T. Tu, Emily Carrier, Amanda E. Lechner, Kevin Draper

![]() labama’s pass on the Medicaid expansion under national health reform leaves the Birmingham region’s low-income, uninsured adults with a patchwork safety net widely regarded as limited and inadequately funded, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source).

labama’s pass on the Medicaid expansion under national health reform leaves the Birmingham region’s low-income, uninsured adults with a patchwork safety net widely regarded as limited and inadequately funded, according to a new Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) study of the region’s commercial and Medicaid insurance markets (see Data Source).

After making early progress in setting up a state-run health insurance exchange, Alabama ultimately reversed course and ceded the exchange’s operation to the federal government. Transitioning from the current minimally regulated commercial insurance market to the more stringent standards required by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) poses many challenges for Alabama. One is federal control of the insurance rate-review process, after federal authorities deemed Alabama’s process ineffective. Another is potential rate shock and instability when the ACA’s rating restrictions take effect—especially in the nongroup, or individual, market, which now has no rating restrictions. Key factors likely to influence how national health reform plays out in the Birmingham area include:

- Uncompetitive health insurance market. With Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama (BCBS) controlling about 85 percent of the commercial market, Birmingham ranks among the least competitive insurance markets in the country. While BCBS lacks major rivals, the insurer reportedly does not exercise negotiating leverage in a heavy-handed manner with providers. BCBS obtains better provider discounts than other insurers but reportedly could pursue lower rates given its market clout. Compared to many markets, Birmingham-area insurance premiums are moderate.

- Traditional benefit designs. The predominant commercial offerings are traditional preferred provider organization (PPO) products with modest out-of-pocket cost sharing, comprehensive provider networks and few, if any, care-management features. High-deductible health plans have yet to gain a significant foothold in the market, and limited-provider networks and other innovations have gained even less traction.

- Academic medical center dominates market. The University of Birmingham at Alabama (UAB) Health System is the market’s leading provider, with a flagship hospital that serves as a specialty referral center for the entire state. Outside of UAB, which employs many physicians, there has been little hospital-physician alignment in the market, although physician employment by other systems is growing. Likewise, there has been little physician consolidation into large practices. With the exception of the small health maintenance organization (HMO) VIVA Health, risk sharing between commercial health plans and providers is nonexistent.

- Stringent Medicaid eligibility. Alabama sets Medicaid eligibility at minimum federal levels: low income cutoffs for categorically eligible groups and no coverage for nondisabled, childless adults. Despite these restrictive standards and the absence of state outreach activities, Medicaid enrollment grew 24 percent in greater Birmingham from 2008 to 2012, as the economic downturn led to job losses.

- No Medicaid managed care to date. The state Medicaid agency contracts directly with providers on a fee-for-service basis. However, motivated by the need to slow the growth of Medicaid spending, Alabama recently enacted a law mandating new regional care organizations (RCOs). Beginning in 2016, RCOs will assume full financial risk for enrollee care. With little or no experience with capitated payments—fixed per-member, per-month amounts—it is uncertain how prepared providers will be to manage care and take on financial risk.

- A weak, fragmented safety net. The safety net has limited funding, few providers—one federally qualified health center (FQHC), a few hospitals providing specialty and inpatient care, and several free clinics—and little coordination among providers.

- Uncertainty about the exchange. As in all states with federally run exchanges, decisions about which carriers, products and rates would be available were delayed. When the exchange opened on Oct. 1, technical glitches restricted many consumers’ access to product and price information. Only BCBS and Humana are offering nongroup exchange products, confirming respondents’ predictions of limited competition. Two defining characteristics of the commercial market are unlikely to change: the dominance of BCBS and the lack of product innovation.

Table of Contents

Market Background

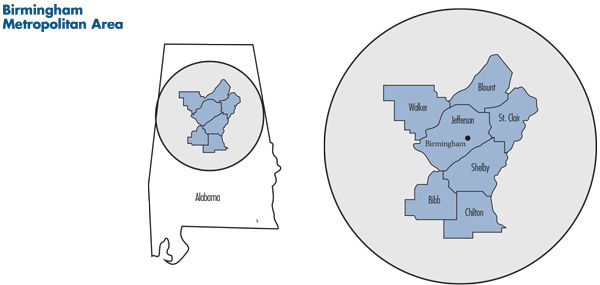

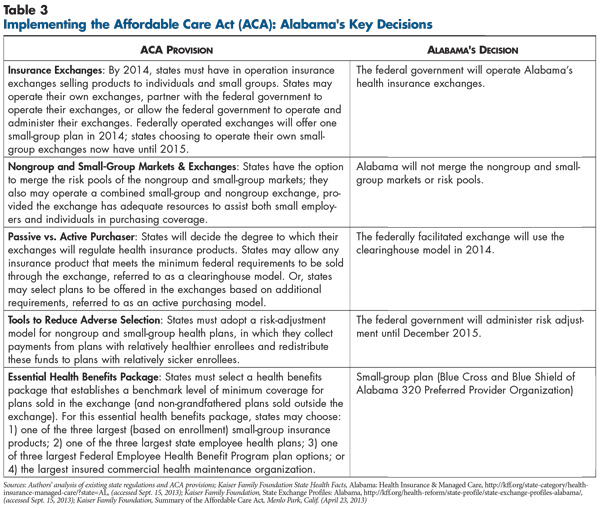

![]() ome to more than 1.1 million people, the Birmingham metropolitan area in north-central Alabama encompasses seven counties: Jefferson—whose county seat is Birmingham—Shelby, Walker, Blount, St. Clair, Bibb and Chilton (see map). Over the past decade, the region’s population has grown more slowly than the nationwide metropolitan average (see Table 1).

ome to more than 1.1 million people, the Birmingham metropolitan area in north-central Alabama encompasses seven counties: Jefferson—whose county seat is Birmingham—Shelby, Walker, Blount, St. Clair, Bibb and Chilton (see map). Over the past decade, the region’s population has grown more slowly than the nationwide metropolitan average (see Table 1).

Greater Birmingham has a higher proportion of white residents and twice the proportion of black residents as the average metropolitan area—28 percent vs. 14 percent, respectively—but far fewer other minorities. The region fares worse than other metropolitan areas on a number of key health indicators, including the prevalence of diabetes, obesity, tobacco use and self-reported fair/poor health status. Alabama is among the lowest-income states in the nation, ranking 42nd in median income.1 As the economic and financial hub of Alabama, Birmingham is better off than much of the state, but the share of residents living in poverty is above average for metropolitan areas—17 percent vs. 14 percent. A racial divide persists with respect to income: Nearly a quarter of blacks live below the poverty line, compared to one in 10 whites.2

Despite below-average income and health status, the Birmingham region fares relatively well on some key economic indicators, including health insurance coverage and unemployment. The area’s rate of private health insurance coverage closely matches the nationwide metropolitan average (56.6% vs. 56.3%), and the proportion of residents without health coverage is lower than the nationwide average (13.6% vs. 17.0%). Before the Great Recession, Birmingham’s unemployment rate was exceptionally low at 3.1 percent in 2007, compared to the metropolitan average of 4.5 percent. During the economic downturn, unemployment peaked at 10.3 percent but remained consistently below the national average. By February 2013, unemployment had fallen to 7.2 percent, compared to 7.7 percent nationally.3 The 2011 bankruptcy of Jefferson County—at the time, the largest-ever municipal bankruptcy—contributed to unemployment, with the county laying off 10 percent of its workforce in 2011 and an additional 15 percent to 20 percent in 2012.4

In the 1950s and 1960s, Birmingham’s economy relied on the iron and steel industry. With that sector’s decline, the region’s economy diversified. The University of Alabama at Birmingham is the region’s largest employer, followed by government at the federal, state and local levels, as well as AT&T; Regions Financial, a commercial bank; KBR, an engineering and construction firm; and several health systems.

Since the 1960s, the city of Birmingham has experienced a population decline and a growing poverty rate (25% in 2010), as the iron and steel industry collapsed and middle-class families left for the suburbs. In contrast, the communities south and southeast of the city are among the metropolitan area’s most affluent and fastest growing.

Little Insurance Regulation

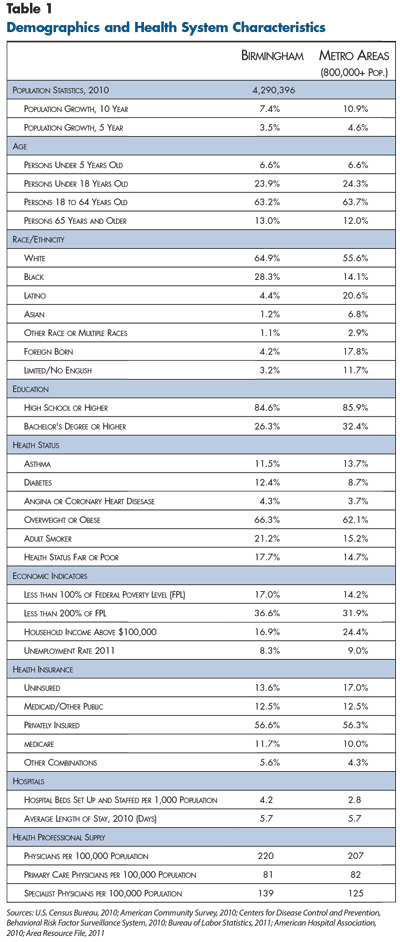

![]() onsistent with Alabama’s politically conservative orientation and approach to business oversight in general, the state imposes little regulation on the commercial health insurance market (see Table 2). The nongroup market has no rating restrictions at all. In the small-group market (2–50 workers), Alabama prohibits rating by industry or tobacco use but allows premiums to vary by age, health status and gender. The state does limit the extent of small-group premium variation: Base rates can vary by a factor of 4:1 based on age, plus or minus 25 percent based on group health status, and plus or minus 15 percent based on group size.

onsistent with Alabama’s politically conservative orientation and approach to business oversight in general, the state imposes little regulation on the commercial health insurance market (see Table 2). The nongroup market has no rating restrictions at all. In the small-group market (2–50 workers), Alabama prohibits rating by industry or tobacco use but allows premiums to vary by age, health status and gender. The state does limit the extent of small-group premium variation: Base rates can vary by a factor of 4:1 based on age, plus or minus 25 percent based on group health status, and plus or minus 15 percent based on group size.

Compared to most states, Alabama imposes fewer benefit mandates on fully insured products and tends not to mandate coverage of more costly services—for example, infertility treatment, comprehensive autism treatment, some types of cancer treatment and access to clinical trials.5

State law requires certain insurers—Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama and HMO plans—to submit small-group and nongroup premium rates to the state Department of Insurance (DOI) for approval 30 days prior to a policy’s issue or renewal date. Reportedly, DOI does not disapprove rate increases outright but does discuss initial rate filings with health plans. This process sometimes results in lower rate increases than those originally proposed by insurers.

Since the late-1990s, Alabama has operated a high-risk pool, but it is restricted to people with at least 18 months of uninterrupted group coverage as defined under the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. In 2010, about 2,100 Alabama residents were enrolled in the state high-risk pool. The ACA required all states to offer a temporary high-risk pool for people denied coverage because of health status, but Alabama declined to operate the pool, leaving the task to the federal government.

Restrictive Medicaid Eligibility

![]() labama sets Medicaid eligibility at minimum federal levels. Children 5 and younger and pregnant women are covered up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, while children older than 5 are covered just up to the poverty level. Parents of dependent children are covered to 23 percent of poverty if working and 10 percent if unemployed. Nondisabled, childless adults are not eligible at all. While Alabama sets stringent Medicaid income cutoffs for children, the state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), ALL Kids, offers coverage to children with family incomes up to 300 percent of poverty—a more expansive eligibility standard than in many states.

labama sets Medicaid eligibility at minimum federal levels. Children 5 and younger and pregnant women are covered up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, while children older than 5 are covered just up to the poverty level. Parents of dependent children are covered to 23 percent of poverty if working and 10 percent if unemployed. Nondisabled, childless adults are not eligible at all. While Alabama sets stringent Medicaid income cutoffs for children, the state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), ALL Kids, offers coverage to children with family incomes up to 300 percent of poverty—a more expansive eligibility standard than in many states.

Despite restrictive Medicaid eligibility, about 20 percent of Birmingham-area residents were covered by Medicaid at some point in 2012,6 largely reflecting the high prevalence of poverty among pregnant women and children. During the economic downturn, loss of jobs and reductions in income led to increased Medicaid eligibility and enrollment. From 2008 to 2012, enrollment grew by 19 percent statewide and 24 percent in Birmingham,7 even in the absence of state outreach activities.

In 2012, the Medicaid program faced a crisis when the state’s initial 2013 budget mandated a 30 percent funding reduction, despite increased enrollment. The crisis was narrowly averted when the state diverted money from a state oil and gas royalty trust fund to cover the Medicaid shortfall. However, this fix was temporary, and budget pressures persist.

Alabama’s Medicaid program currently operates under a traditional fee-for-service model, with the Medicaid agency negotiating payment rates directly with providers and the state retaining all financial risk. In 2013, Alabama opted to overhaul Medicaid financing and care delivery by enacting a law that eventually will shift all financial risk for enrollees’ care to entities known as regional care organizations, or RCOs, which must be provider-sponsored entities. Beginning in 2016, the RCOs will receive capitated—fixed per-member, per-month—payments from the state to pay providers and manage patient care. Some observers expressed concern that the state may be tempted to address ongoing budget pressures by setting capitation rates too low, which could threaten the financial viability of fledgling RCOs and their ability to deliver acceptable access and quality.

In moving from fee for service to managed care, state policy makers hope to slow Medicaid spending growth. The RCOs reportedly are based on Oregon’s new coordinated care organization (CCO) model; however, there appear to be few parallels between the two states’ Medicaid programs. Long before Oregon implemented CCOs, the state had a strong group of Medicaid managed care plans with abundant experience taking full financial risk and managing care for enrollees within integrated delivery systems. In contrast, Alabama will be entering uncharted territory as it transitions from a fragmented, largely unmanaged fee-for-service delivery system.

BCBS Dominates Insurance Market

![]() he commercial health insurance market in Birmingham—and Alabama generally—is perhaps the least competitive market nationwide. The dominant carrier, nonprofit Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama, controls an estimated 85 percent of the overall commercial market. BCBS is especially dominant in the small-group segment, with an estimated 95-percent market share. While the nongroup segment has more carriers than the small-group segment, BCBS still commands about 85 percent of the market. BCBS benefits from strong consumer brand recognition, reinforced by heavy advertising. The large-group segment is the most competitive. Many large employers self-insure and can choose from a multitude of local/regional and national third-party administrators. Nonetheless, BCBS still controls an estimated 75 percent of the large-group market.

he commercial health insurance market in Birmingham—and Alabama generally—is perhaps the least competitive market nationwide. The dominant carrier, nonprofit Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama, controls an estimated 85 percent of the overall commercial market. BCBS is especially dominant in the small-group segment, with an estimated 95-percent market share. While the nongroup segment has more carriers than the small-group segment, BCBS still commands about 85 percent of the market. BCBS benefits from strong consumer brand recognition, reinforced by heavy advertising. The large-group segment is the most competitive. Many large employers self-insure and can choose from a multitude of local/regional and national third-party administrators. Nonetheless, BCBS still controls an estimated 75 percent of the large-group market.

BCBS has two noteworthy commercial competitors in Birmingham: national for-profit UnitedHealth Group and local HMO VIVA Health, owned by the UAB Health System. United’s niche includes high-deductible health plans, wellness programs, online consumer tools and data capabilities. United participates in the nongroup market through a subsidiary, Golden Rule, and in the group market as UnitedHealthcare. As the largest HMO in the market, VIVA’s competitive advantage centers on managed care capabilities, including care management and utilization management. VIVA maintains a presence in all commercial group segments but not the nongroup market. While VIVA is a tiny fraction of BCBS in size, it does provide coverage for a majority of UAB employees. National carrier Humana also has a presence in the market.

BCBS reportedly maintains dominance by keeping administrative costs lower and obtaining better provider discounts than competing insurers. BCBS’ use of in-house staff rather than brokers to sell insurance policies reportedly has helped the carrier to keep administrative costs down. BCBS’ ability to obtain provider discounts reportedly has been a major factor in keeping premium levels moderate in the Birmingham area compared to many markets—likely a key factor behind Birmingham’s relatively high rates of private insurance. At the same time, several market observers noted that the company does not demand particularly steep provider discounts. According to one market observer, “I have heard providers say [privately]…that Blue Cross Blue Shield could squeeze them [providers] a lot tighter if they wanted to.” As another market insider noted, squeezing providers harder—especially hospitals—might prompt a community backlash and invite more scrutiny from state regulators and policy makers.

Respondents uniformly characterized Birmingham’s insurance market—and the health system generally—as lacking innovation. One observer spoke of the market being stuck in a “time warp,” while another described it as “behind the curve” on new approaches to insurance benefit design, provider payment and care delivery. The most popular benefit design in the market is a traditional PPO product with low-to-moderate cost sharing—$250 average individual deductible among large groups, increasing to $500 to $1,000 as group size decreases. Fixed copayments remain common rather than coinsurance, where patients pay a percentage of the total bill. High-deductible health plans have gained far less traction in Birmingham than many other markets; by some estimates, these products cover fewer than one in 10 of commercially insured people. Broad provider networks remain the norm, even for VIVA’s HMO offerings. While VIVA, United and other carriers cannot quite match the breadth of BCBS’ comprehensive provider network, their networks generally include all of the hospitals and at least 90 percent of the physicians in greater Birmingham. A few experiments with limited-network products over the years were withdrawn when they failed to capture purchaser interest.

Innovative payment arrangements between plans and providers have not been attempted in most of the Birmingham market. The only plan to engage in risk sharing with providers is VIVA, which uses capitation as the payment method for some hospitals and large, hospital-owned physician practices in its network. However, lack of widespread integration and consolidation in the provider sector prevents VIVA from using risk sharing broadly.

UAB Dominates Hospital Market

![]() he market’s leading provider is the University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System. UAB Hospital is the state’s top academic medical center and serves as a tertiary referral center not just for Alabama, but also for much of the Southeast. In addition, Children’s Hospital of Alabama at UAB serves as a major regional referral center for pediatrics. UAB reportedly obtains consistently higher payment rates from insurers than other hospitals. One market observer referred to the Birmingham market as a “bilateral monopoly,” given the dominant positions of BCBS and UAB.

he market’s leading provider is the University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System. UAB Hospital is the state’s top academic medical center and serves as a tertiary referral center not just for Alabama, but also for much of the Southeast. In addition, Children’s Hospital of Alabama at UAB serves as a major regional referral center for pediatrics. UAB reportedly obtains consistently higher payment rates from insurers than other hospitals. One market observer referred to the Birmingham market as a “bilateral monopoly,” given the dominant positions of BCBS and UAB.

Respondents had mixed views about the competitive position of hospitals other than UAB. Other hospitals in the market include four hospitals in the St. Vincent’s Health System, which is part of Ascension Health, the largest Catholic and nonprofit hospital system in the country; nonprofit Baptist Health System with three hospitals in greater Birmingham; Trinity Medical Center, owned by national for-profit chain Community Health Systems; and Brookwood Medical Center, owned by Tenet Health Care, another for-profit national chain. Some observers suggested that these hospitals struggle to differentiate themselves and their brands. However, other respondents pointed to Brookwood’s reputation for orthopedics and St. Vincent’s reputation for high-touch care and obstetrics.

Except for UAB, which employs a large number of physicians, Birmingham has less hospital employment of physicians and other forms of hospital-physician alignment than many markets. Despite Baptist Health and Brookwood increasing their employment of physicians in recent years, most hospitals and physicians in the market still have what one observer described as “a very 1950s kind of relationship.” Birmingham also has seen relatively little consolidation of physicians into large practices; most physicians outside the UAB system are still in small, independent practices. Given the lack of provider consolidation and integration—aside from UAB, whose focus is on specialty and tertiary care—it is not surprising that the market has neither Medicare nor commercial activity around accountable care organizations.

Compared to other metropolitan areas, Birmingham has an average supply of primary care physicians and a slightly above-average supply of specialists in the entire market, but the supply available to the safety net is widely regarded as seriously inadequate.

Weak, Fragmented Safety Net

![]() irmingham’s uninsured adults—whose care is financed largely by county funding, supplemented by charity care—face serious difficulties accessing both primary and specialty care. Unlike the resources available to pregnant women and children with Medicaid or CHIP coverage,8 the safety net serving uninsured adults is a limited patchwork of providers lacking integration or coordination.

irmingham’s uninsured adults—whose care is financed largely by county funding, supplemented by charity care—face serious difficulties accessing both primary and specialty care. Unlike the resources available to pregnant women and children with Medicaid or CHIP coverage,8 the safety net serving uninsured adults is a limited patchwork of providers lacking integration or coordination.

Three hospitals—UAB, St. Vincent’s East and Baptist Health’s Princeton Medical Center—reportedly are the main safety net providers for adults. Until 2012, Jefferson County operated a dedicated safety net hospital, Cooper Green Mercy Hospital, which provided the majority of inpatient care to the county’s low-income, uninsured residents. Because of the county’s bankruptcy and Cooper Green’s financial problems, the hospital stopped providing inpatient and emergency care in 2012. Cooper Green became an outpatient center, but instability has led to the departure of much of the clinical staff, leading some observers to question whether Cooper Green can fulfill its intended new role as a source of coordinated, low-cost outpatient care.

The community’s sole federally qualified health center, Birmingham Health Care (BHC), which operates six clinics, has been embroiled in financial scandals involving the center’s former leadership team.9 UAB has severed all clinical partnerships between the two organizations, and BHC reportedly has done little to coordinate with other safety net providers. A number of small free clinics, which tend to focus on homeless populations or undocumented immigrants, offer some outpatient care.

Birmingham’s limited, fragmented safety net is unlikely to see significant changes under health reform. With Alabama’s rejection of a Medicaid expansion, there will be no influx of federal dollars flowing to safety net providers. One market observer predicted that the safety net will continue to “hobble along…pretty much as it is now.”

Reluctantly Inching Toward Reform

![]() espite the state joining a lawsuit challenging the ACA’s constitutionality, two successive Republican governors initially appeared willing to implement the law’s key provisions, with the state obtaining federal and private foundation grant funding to prepare for ACA implementation.

espite the state joining a lawsuit challenging the ACA’s constitutionality, two successive Republican governors initially appeared willing to implement the law’s key provisions, with the state obtaining federal and private foundation grant funding to prepare for ACA implementation.

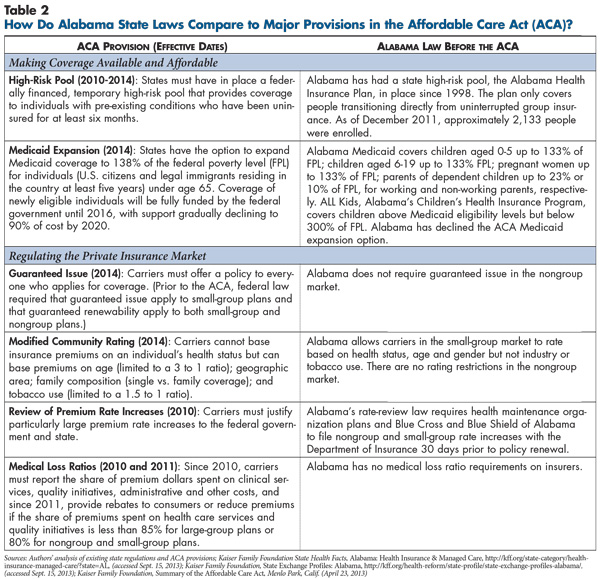

In 2012, however, momentum stalled, and the state reversed course. Some observers suggested that state policy makers spent much of the first half of 2012 waiting for the U.S. Supreme Court to strike down the ACA. By the time the Supreme Court upheld the bulk of the ACA but struck down the mandatory Medicaid expansion, opposition to all aspects of the reform law was entrenched in the state. In November 2012, the governor announced the state would neither expand Medicaid nor implement a state-based exchange (see Table 3). Key developments at the state level include:

No Medicaid expansion. If Alabama expanded Medicaid to 138 percent of poverty, a UAB study estimates 530,000 state residents would be newly eligible.10 In the Medicaid take-up scenario considered most likely by UAB researchers, approximately 300,000 of these residents likely would have enrolled in Medicaid.

In the absence of Medicaid expansion, adults with incomes between 100 percent and 138 percent of poverty will be eligible for subsidies to buy private coverage on the exchange. However, nondisabled, childless adults with incomes below 100 percent of poverty have no path to insurance under the ACA, which specifies that they are ineligible for subsidies. Some respondents suggested that Alabama eventually may again reverse course and expand Medicaid because, as one market observer put it, “There’s simply too much federal money left on the table [by declining the expansion].” One possible blueprint was provided by Arkansas, which recently received a federal waiver to give adults newly eligible for Medicaid—including those with incomes below poverty—premium subsidies financed with federal Medicaid funding to purchase coverage on the state health insurance exchange. This approach allows states to expand coverage for low-income adults without increasing the rolls of their traditional Medicaid programs.

Federally facilitated exchange. Initially, a state-run health insurance exchange drew wide support from state policy makers, even among those opposing the ACA overall. A state-based exchange was seen both as a way to spur competition in the state’s commercial insurance market and as an important safeguard against ceding control to the federal government. In mid-2011, Gov. Robert Bentley (R) established the Alabama Health Insurance Exchange Study Commission. By late 2011, the commission had unanimously endorsed a state-based exchange and issued recommendations on structure and financing. In 2012, however, the governor withdrew support for a state-based exchange. As a result, the federal government assumed responsibility for implementing and running Alabama’s exchange.

Alabama declined to choose a benchmark plan for essential health benefits, so the largest small-group plan—BCBS 320 Plan, a PPO product—became the benchmark by default. The plan is comparable to other small-group products and slightly less comprehensive than the state employee plan. Alabama does not plan to conduct any plan management or consumer assistance functions related to the exchange.

Federal rate review. Under the ACA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is charged with determining whether states have effective processes in place for reviewing small-group and nongroup premiums. While Alabama has a review process for BCBS and HMO rates, HHS found Alabama to be one of six states with an ineffective rate-review process. As a result, HHS will assume control of Alabama rate reviews until it determines that state officials have strengthened the review process to meet federal standards.

In addition to these state-level developments, stakeholders in the Birmingham market, as in health care markets around the country, raised a number of similar questions and concerns about setting premiums for products offered in the exchange, including:

- Risk pools—How sick will the newly insured be compared to the currently insured? Will higher rates lead the young and healthy to choose to pay the tax penalty instead of enrolling in coverage? Which small groups will drop coverage and how will this affect the risk pool?

- Pent-up demand—Will the newly insured make up months and years of forgone care by using large amounts of medical care?

- Expanded benefits—How much utilization will occur, and how much will premiums increase because ACA minimums exceed benefits of many existing plans, especially in the nongroup market?

- Risk adjustment—How will the health status of enrollees be measured, and how will funds be redistributed among carriers? Will this process adequately account for differences in risk profiles of plan members?

Given Alabama’s current lack of rating restrictions for nongroup coverage, new ACA requirements likely will compress premiums substantially, potentially generating rate spikes for younger, healthier enrollees and more affordable rates for older, sicker enrollees. This is less of an issue for small-group coverage, where Alabama already imposes some limits on premium variation, albeit less restrictive than the ACA. Along with these broader concerns, there are some ways these issues could play out more specifically in the Birmingham market:

Slow rollout for exchange. The federally run exchange got off to a slow start, not releasing any premium information until a week before the launch of open enrollment. When the exchange was launched on Oct. 1, technical glitches—exacerbated by a high volume of users—made it difficult for many consumers to access information on product options, premiums and subsidies.

Limited plan participation. Only BCBS, United and Humana are offering products on the small-group exchange. Participation is even more restricted on the nongroup exchange, where only BCBS and Humana are offering products, and Humana’s Birmingham participation is limited to the two most populous counties, Jefferson and Shelby. In the nongroup exchange, monthly premiums for a 50-year-old range from $290 for a bronze plan to $561 for a platinum plan. The nongroup premium for the second-lowest-cost silver plan, which will determine subsidies, is $360 for a 50-year-old.

Contrary to the expectations of many respondents, VIVA decided not to participate in the exchange, at least in the first year. However, VIVA has never participated in the nongroup market, so the company’s decision was consistent with its longstanding strategy. As a small plan, VIVA reportedly did not see the upside to entering a new market at a time of uncertainty and had concerns that any volatility in enrollment could affect its operations adversely. Consistent with respondent expectations, the exchange attracted no new entrants. Unlike many markets across the country where Medicaid plans are poised to compete head-to-head with commercial plans, Alabama has no Medicaid managed care market. And, so far, providers in the Birmingham market have not indicated interest in sponsoring plans on the exchange.

Status quo expected. Respondents suggested that several key features of the Birmingham health care market are likely to remain unaffected by the advent of reform. First, the dominance of BCBS was expected to remain unchallenged by competition on the exchange. Indeed, some observers suggested BCBS might even expand its share of the nongroup market, given its brand strength with consumers. Observers also expected little innovation in health plan product designs and provider payment approaches in the commercial market.

Issues to Track

- How well will Alabama’s federally facilitated health insurance exchange function?

- How, if at all, will the exchange affect competition among health plans? Will the exchange eventually attract new entrants to the market?

- Will Alabama revisit expanding Medicaid during the next two years?

- What changes, if any, will take place in Birmingham’s limited and struggling safety net over the next several years? Will funding continue to fall short and leave low-income, uninsured people with limited access to care?

- How will Medicaid managed care unfold in the Birmingham market? How will regional care organizations be structured and organized? How equipped will the RCOs be to accept financial risk? What impact will the RCO model have on access to care and quality of care for Medicaid patients?

Notes

| 1. | U.S. Census Bureau, Median Household Income by State—Single Year Estimates, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/statemedian/ (accessed Sept. 17, 2013). |

| 2. | U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2006-2010, Detailed Tables, http://factfinder2.census.gov/ (accessed Sept. 17, 2013). |

| 3. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, http://www.bls.gov/cps/ (accessed Sept. 17, 2013); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/lau/ (accessed Sept. 17, 2013). Nationwide metropolitan average unemployment rates were calculated by the authors using the Current Population Survey database. |

| 4. | HealthLeaders-InterStudy, Birmingham Market Overview, Nashville, Tenn. (January 2012). |

| 5. | National Conference of State Legislatures, State Health Insurance Mandates and the PPACA Essential Benefits Provisions, http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/health/state-ins-mandates-and-aca-essential-benefits.aspx (accessed Sept. 17, 2013). |

| 6. | Alabama Medicaid Agency, Alabama Medicaid Statistics 2012, http://medicaid.alabama.gov/documents/2.0_Newsroom/2.6_Statistics/2.6_County_Stats/2.6_FY12_County_Stats_2-12-13.pdf (accessed Sept. 17, 2013). |

| 7. | Alabama Medicaid Agency, http://medicaid.alabama.gov/CONTENT/2.0_newsroom/2.6_Statistics.aspx (accessed July 26, 2013). |

| 8. | Children in ALL Kids (CHIP) have access to a comprehensive network through BCBS, which administers the program. Pregnant women and children in Medicaid have access to county-run primary care clinics, among other resources; children also have access to specialty and inpatient care at Children’s Hospital of Alabama at UAB. |

| 9. | Oliver, Mike, “Ties Between Birmingham Nonprofit and Ex-CEO’s Companies Raise Questions,” The Birmingham News (June 24, 2012); Oliver, Mike, “Birmingham Health Care is the Least Accessible to the Homeless Seeking Health Care, Study Finds,” The Birmingham News (April 26, 2013). |

| 10. | Becker, David J., and Michael A. Morrisey, An Economic Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion in Alabama under the Affordable Care Act, University of Alabama at Birmingham (Nov. 5, 2012). |

Data Source

As part of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) State Health Reform Assistance Network initiative, the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) examined commercial and Medicaid health insurance markets in eight U.S. metropolitan areas: Baltimore; Portland, Ore.; Denver; Long Island, N.Y.; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Birmingham, Ala.; Richmond, Va.; and Albuquerque, N.M. The study examined both how these markets function currently and are changing over time, especially in preparation for national health reform as outlined under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. In particular, the study included a focus on the impact of state regulation on insurance markets, commercial health plans’ market positions and product designs, factors contributing to employers’ and other purchasers’ decisions about health insurance, and Medicaid/state Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) outreach/enrollment strategies and managed care. The study also provides early insights on the impact of new insurance regulations, plan participation in health insurance exchanges, and potential changes in the types, levels and costs of insurance coverage.

This primarily qualitative study consisted of interviews with commercial health plan executives, brokers and benefits consultants, Medicaid health plan executives, Medicaid/CHIP outreach organizations, and other respondents—for example, academics and consultants—with a vantage perspective of the commercial or Medicaid market. Researchers conducted 12 interviews in the Birmingham market between February and July 2013. Additionally, the study incorporated quantitative data to illustrate how the Birmingham market compares to the other study markets and the nation. In addition to a Community Report on each of the eight markets, key findings from the eight sites will also be analyzed in two publications, one on commercial insurance markets and the other on Medicaid managed care.